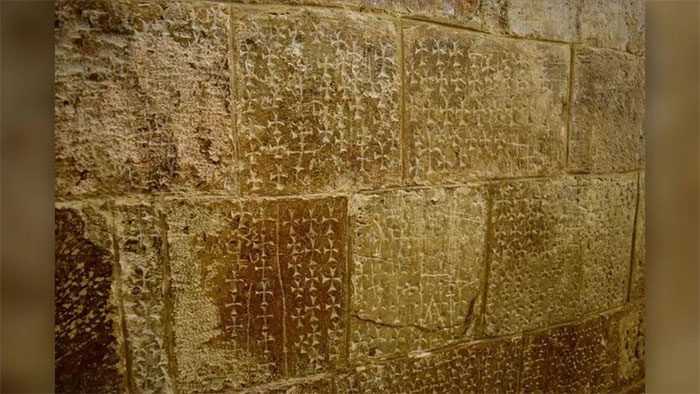

A new study reveals that the mysterious crosses carved on one of the walls of the staircase leading down to the Chapel of St. Helena at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem may not be what was previously imagined.

Until now, religious scholars believed that medieval pilgrims traveling to this sacred site carved the crosses into the walls. However, the new research indicates that only a small number of individuals, possibly stonemasons or artisans, carved these crosses on behalf of the pilgrims, who may have kept dust from the carvings as a sacred souvenir.

The crosses on the wall at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Holy Land of Jerusalem.

Some of the crosses date back to the 14th or 15th century, hundreds of years after the Crusades in the Holy Land (1096-1291), suggesting that post-medieval pilgrims may have created these crosses.

“During the research process, we meticulously examined and analyzed every millimeter of the crosses – their depth, width, and even the hands of those who carved them,” said project leader Amit Re’em, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem.

The research team found that it was likely one person, or a few individuals, responsible for creating these crosses, rather than the hundreds or thousands of pilgrims who visited the church.

Re’em conceived the idea for the research during a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The church was built in the 4th century when St. Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, traveled to Jerusalem and, according to legend, helped discover the site where Jesus was crucified, buried, and resurrected. Constantine had a basilica built there, which later became known as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Together with colleagues Moshe Caine and Doron Altaratz, professors and senior lecturers at the Hadassah Academic College’s Photography Communication Department in Jerusalem, the research team used three photographic techniques to capture the shapes of the crosses: photogrammetry, Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), and gigapixel photography.

For photogrammetry, the team took between 50 to 500 photos of each subject, each from a different angle, and then used software to create a digital 3D image based on the triangulation of all the images.

Meanwhile, with gigapixel photography, similar to zooming in from a global view to a close-up street view on Google Maps, the team captured numerous images of the carved surfaces.

All these techniques helped Re’em investigate the similarities and differences, including the carving techniques, of each cross. Furthermore, as the researchers photographed the crosses, they noticed inscriptions of names and dates carved along them.

Re’em stated: “We found that the crosses were carved around the inscriptions, meaning that the crosses were created at the same time or slightly later than the carved inscriptions.”

After reading about the ongoing research in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, William Purkis, a medieval history reader at the University of Birmingham in the UK, contacted Re’em. Purkis expressed that he shared the same thoughts as the Israeli researchers regarding the findings that these crosses were only created by a few specialists.

It is possible that pilgrims paid a stonemason or artist to carve a cross for them in the church and then kept the dust as a sacred souvenir, Purkis noted.

In medieval times, pilgrims were known to carry small lead vials filled with mementos from the Holy Land, such as water from the Jordan River. Two of these medieval vials are housed in museums – the Cleveland Museum of Art and the British Museum.