During World War II, the United States pursued a bat bomb project aimed at attacking enemy targets. The design involved thousands of bats equipped with tiny incendiary bombs simultaneously striking a target, causing significant damage to the opponent.

Many unique and even bizarre weapon projects were undertaken during World War II. The U.S. bat bomb project was one of them.

The concept of bat bombs to eliminate enemy strength.

Inspiration from Bat Caves

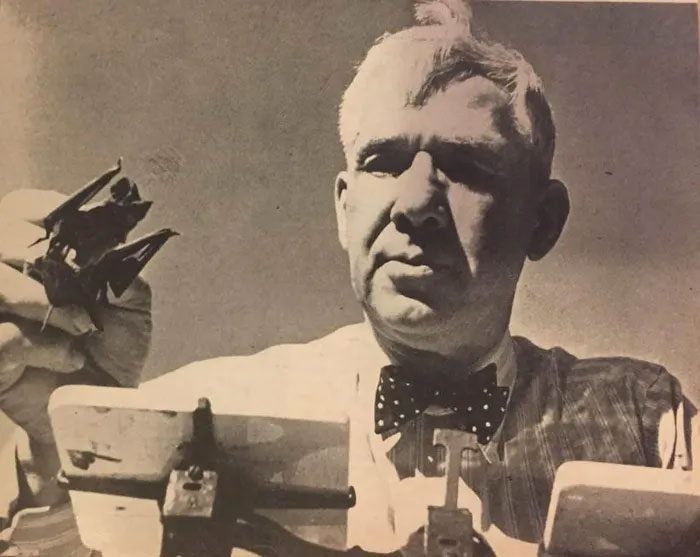

Dr. Lytle Adams was the first to come up with the idea of developing bat bombs to destroy enemy capabilities.

The inspiration for the “bat bomb” emerged after his trip to the Carlsbad Caverns system in New Mexico, home to between 200,000 and 500,000 bats. During migration season, the number could surge to over a million.

This crowded bat colony sparked an “unprecedented” idea in Adams, and the attack on Pearl Harbor weeks earlier motivated him to create a new weapon to give the U.S. military an advantage on the battlefield. On January 12, 1942, Dr. Adams submitted his proposal to then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In the proposal, Dr. Adams suggested that the U.S. use bats carrying tiny incendiary bombs and release them over Japan to incinerate Japanese cities. After receiving Adams’ proposal, President Roosevelt tasked his aides to assess the feasibility of developing the bat bomb weapon.

Successful Tests, Then Abandonment

At the time, experts found the project feasible. Therefore, the U.S. initiated the bat bomb weapon project, and Dr. Adams joined the team of scientists working for the U.S. government. The plan involved capturing and studying hundreds of bats.

Next, they researched and developed incendiary devices so that a 30-gram bat could carry them to the target. Consequently, a bomb weighing less than 20 grams was created. The scientists attached this weapon to the bats. However, during testing, some bats carrying incendiary bombs flew out of the test area, resulting in a small fire. On December 15, 1943, the U.S. successfully tested bat bombs at a testing site in Utah.

The research team of Dr. Lytle Adams tested various species of bats.

Adams built a team of individuals who could help make the project a reality. His assembled research group was as eccentric as he was. It included a mammalogist from the Los Angeles County Museum, Dr. Jack von Bloeker, and students working in his laboratory. Later, Dr. Theodore Fieser, the creator of napalm, was added to the team.

Strangely, the group also included non-scientists, such as actor and pilot Tim Holt, a bodybuilder, and a former hotel manager. Notably, former mob boss Patricio “Patsy” Batista and a former lobster fisherman who became a member of the U.S. Navy also participated in this project.

The research team tested various bat species before choosing the Mexican free-tailed bat. These bats are very small, weighing only 8.5 grams, yet can fly well while carrying a bomb three times their body weight.

The bombs were made from nitrocellulose casings filled with napalm. Nitrocellulose objects are extremely flammable and can self-ignite over time. After several tests, the team decided to attach the bombs to the bats’ bodies using glue.

In May 1943, about 4,000 bats were captured and placed in refrigerators to induce a hibernation state. Tests with dummy bombs were conducted. A cage was dropped from a B-52 at an altitude of 1,500 meters, and the results were disastrous. Most bats began to recover from hibernation while plummeting but could not fly and died upon impact with the ground.

After several adjustments, the experiment was repeated with real bombs at a secondary base of Carlsbad Military Airport. This led to another accident. Many bats carrying bombs escaped and crawled into the underside of a fuel barrel. When the bombs they carried exploded, the testing area was engulfed in flames.

After this incident, the Air Force transferred the project to the Navy, renaming it “Project X-Ray.” The bat bomb was then handed over to the Marine Corps for deployment.

This unit made several modifications and achieved remarkable success during testing, leading the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) to conclude that bat bombs could effectively ignite thousands of fires.

Another round of testing was planned, but the fleet commander canceled the plan upon realizing that the bats were not prepared for combat until 1945. Thus, after spending $2 million (nearly $30 million today), the bat bomb project was shelved.

Nevertheless, even after Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II, Dr. Adams insisted that his bat bombs would cause far greater destruction than atomic bombs while being less lethal.

In reality, if the bat bombs had been used as intended, the resulting fires would still have caused casualties among soldiers, children, civilians, and even the bats themselves. It is best that such destructive weapons are never used.