Two weeks of camping along the mosquito-infested and muddy banks of the Kolyma River in Russia may not seem like the most exciting business trip. However, virologist Jean-Michel Claverie is willing to embrace these hardships to uncover the truth about “zombie viruses”—one of the potential public health risks posed by climate change.

According to Bloomberg, Claverie’s discoveries shed light on the harsh realities of global warming as it causes permafrost—frozen for millennia—to thaw. This permafrost, once a habitat for various organisms, provides ideal conditions for preserving organic matter: dark, oxygen-free, and with minimal chemical activity. In Siberia, it can reach depths of up to 1 km, making it the only place in the world with such deep permafrost.

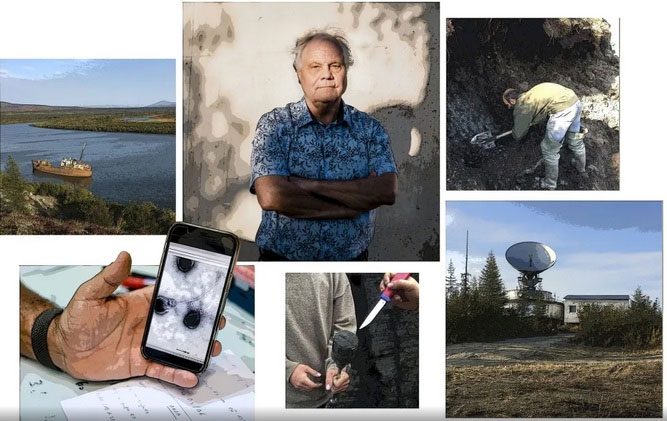

Jean-Michel Claverie has spent years studying “zombie viruses” hidden in permafrost. (Photo: Bloomberg)

Claverie, 73, has dedicated over a decade to studying “giant” viruses, including those nearly 50,000 years old found deep within the permafrost in Siberia.

The Earth has warmed by 1.2 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, and scientists predict that the Arctic could be ice-free during summer by the 2030s. There are growing concerns that a warmer climate will release greenhouse gases like methane into the atmosphere due to the evident thawing of permafrost in the region. However, “dormant” pathogens are a less noticed danger.

In 2022, Claverie’s team published research revealing they had extracted several ancient viruses from Siberian permafrost, all capable of infection.

In an interview at his laboratory at Aix-Marseille University in France, Claverie stated: “With climate change, we have become accustomed to the dangers coming from the South (diseases from warm tropical regions). Now, we are realizing that there may be dangers coming from the North as permafrost melts and releases bacteria and viruses.”

Jean-Michel Claverie in his laboratory at Aix-Marseille University (France). (Photo: Bloomberg)

A heatwave in Siberia during the summer of 2016 triggered anthrax spores, resulting in dozens of infections, one fatality, and the deaths of thousands of reindeer.

In July this year, a group of scientists announced findings suggesting that even multicellular organisms can survive in permafrost in a dormant metabolic state. This team successfully revived a 46,000-year-old roundworm from Siberian permafrost simply by rehydrating it. Teymuras Kurzchalia from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Germany, who participated in the study, stated: “The fundamental idea is that we can halt life and then revive it.”

For many years, global health agencies and various governments have been monitoring infectious diseases that humans have no immunity against and for which no drug treatments exist. The World Health Organization (WHO) added “Disease X” to its shortlist of pathogens considered high priority for research and for developing a roadmap to prevent outbreaks in 2017. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to global lockdowns for several months, these efforts have been intensified.

WHO spokesperson Margaret Harris stated: “WHO is working with over 300 scientists to review evidence of all strains of viruses and bacteria that could cause outbreaks and pandemics, including those that could emerge as permafrost thaws.”

Although largely unrelated, Claverie’s own research encompasses a similar scope. In 2014, Claverie first demonstrated that “living” viruses could be extracted from Siberian permafrost and successfully revived them. For safety reasons, his research has focused solely on viruses that pose no risk of accidental infection to humans.

In 2019, his team isolated 13 new virus types, including one frozen under a lake over 48,500 years ago, from seven permafrost samples in Siberia. In publishing these findings in a 2022 study, Claverie emphasized that infection from an ancient, unknown pathogen in humans, animals, or plants could have “disastrous” consequences.

Claverie remarked: “50,000 years back takes us to the time when Neanderthals disappeared. If Neanderthals died from a disease caused by an unidentified virus and that virus resurfaces, it could pose a danger to us.”