NASA believes that regions with terrain “sculpted” by ice, water, and dust, such as Terra Sirenum on Mars, may be harboring life.

A new study published in the scientific journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment suggests that tiny organisms may find suitable shelter just below the surface in some areas of Mars today.

The lead author, Aditya Khuller from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), stated: “If we are trying to find life anywhere in the universe today, then the ice regions on Mars are probably one of the most accessible places.”

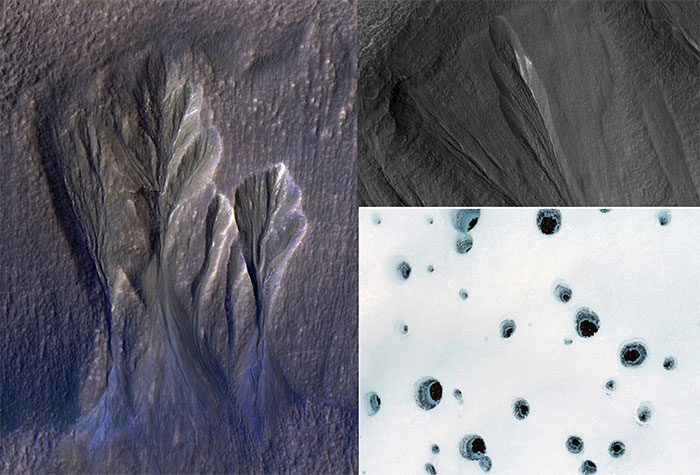

Terra Sirenum (left) and Dao Vallis (top right) on Mars may have cryoconite hole structures similar to those found in Alaska’s icy regions on Earth (bottom right) – (Photo: NASA).

Mars has two types of ice: frozen water and frozen carbon dioxide. The new study focused on the first type.

A large amount of water ice on Mars formed from snow mixed with dust that settled on the surface over a series of glacial periods spanning millions of years, creating a speckled ice with dust particles.

Although the dust particles can obscure light in deeper ice layers, they play a crucial role in explaining how pockets of liquid water may form within the ice when exposed to sunlight.

Black dust, which absorbs more sunlight than the surrounding ice, can warm the ice and cause it to melt at depths of several tens of centimeters below the surface.

On the Red Planet, atmospheric effects make melting difficult at the surface, but these obstacles do not exist beneath a layer of dusty snow or glacier.

On Earth, dust within the ice can create cryoconite holes, small cavities that form in the ice when wind-blown dust settles, absorbs sunlight, and melts deeper into the ice each summer.

Eventually, as these dust particles move farther away from sunlight, they stop sinking but still generate enough heat to maintain a pocket of melted water around them.

These pockets can nourish a thriving ecosystem with simple life forms such as bacteria.

Co-author Phil Christensen from Arizona State University in Tempe, who leads the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera on NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter, noted that he and colleagues have previously discovered exposed water-ice dust layers in canyons on Mars.

In the new study, they propose that in those locations, the dusty ice allows enough light for photosynthesis at depths of 3 meters below the surface, where liquid water pockets remain insulated from evaporation by the overlaying ice.

Specifically, regions between 30 and 40 degrees latitude on Mars, in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, will be the most promising areas for exploration.