Edwin Lutyens

(Photo: knebworthhouse)Construction Period:

1912 – 1931- Location: New Delhi, India

In April 1912, three middle-aged British men, appointed by the Secretary of State for India, surveyed the mountains, foothills, and plains around Delhi while seated unsteadily on the backs of elephants. They were tasked with finding a site for a new capital for the largest colony of the British Empire. The decision was made to move the capital of India from Calcutta to Delhi and to construct a city for 30,000 residents, including ministerial offices to govern the self-governing territory, with the Vice Regal Lodge as its main ornament.

The appointed individuals included Edwin Lutyens, the architect who ultimately determined the site located 5 km southwest of Delhi, which included Raisina Hill. The flat-topped peak and the independent structure of the Vice Regal Lodge were designed to resemble a palace, requiring a grandiose architectural structure. From this lodge, an axis extended to the Friday Mosque (Jama Masjid) in Shahjahanabad, the historical Delhi city of the Mughal dynasty, while another axis, the King’s Way or Rajpath, ran eastward, forming a wide ceremonial route leading to the Vice Regal Lodge.

Lutyens was undoubtedly a solid choice for the role of architect. In his generation, he stood out as England’s leading architect, designing many grand residences for the elite business class under King Edward and affirming the role of the British Empire’s architecture. Lord Herbert Baker, another distinguished British architect, was his colleague on this monumental expedition.

Rajpath – the grand avenue leading west to the Vice Regal Lodge,

with the Jaipur Column standing proudly in front.

East and West

While designing the Vice Regal Lodge and using the maritime routes by steamship between India and his studio in London, Lutyens could sketch what he observed and noted during his first trip to India. One morning, he visited the Red Fort in Delhi and envisioned the movement of historical fountains, seeking to understand the auditory and visual effects of flowing water. This memory later influenced his water usage throughout the city, most magnificently in the water lily fountains within his Mughal gardens and on the roof of the massive building, where he transformed the dome motif to create a bowl-shaped fountain.

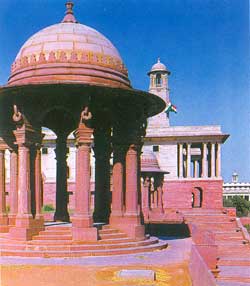

Despite the abundance of advice, there was no detailed guidance, especially regarding the need to incorporate what was deemed local or traditional elements of Indian architecture, such as Indian-Saracen pointed arches. The architect responded by disregarding stylistic books and returning to first principles. Lutyens understood that in the harsh light of the Indian plains, color and form were not paramount. Therefore, he chose Mughal architecture by applying polished stone, emulating the Chhatri, a decorative thin projecting element that casts deep shadows and highlights the horizontal spread of the façade.

“Shadow Play” – Lutyens employed the decorative thin projecting element resembling swords,

inspired by Chhatri in Mughal architecture.

Lutyens further accentuated the structure by using a two-tone stone of red – Dholpur sandstone to construct the Vice Regal Lodge and two of Baker’s ministerial offices, which still retain their exquisite appeal to this day.

The resulting synthesis of these elements, combined with his theoretical understanding of Greco-Roman art, is truly unique. The interaction between solid and void creates a striking impression, with proportions reflecting more Italian characteristics than the expansive openings necessary to illuminate the interiors of Northern Europe.

|

| Lutyens skillfully handled the chhatri in Mughal architecture, or the protruding element on the roof, and Dholpur red stone. |

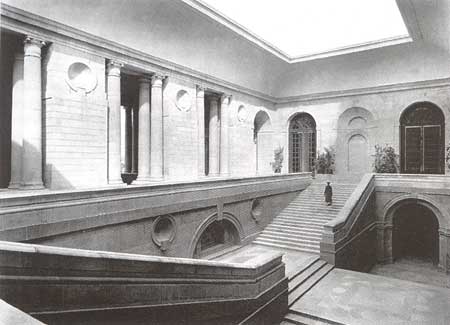

Small window openings, set deep inside, also create a very convincing effect, the grand staircase group placed under the open dome for stargazing, the intertwining of flat land strips creating steps and porticos, columns, and courtyards, all produce a system of forms deeply characteristic of the subcontinent – all resolved convincingly within a single gigantic structure with 340 rooms, yet Lutyens still found time to design child-sized furniture for the nursery within the lodge.

Beneath the massive dome is the most famous feature of the building, the circular Durbar Hall, where the Vice Regal throne is positioned overlooking the main entrance. A collection of luxurious rooms, including a drawing room, ballroom, library, and dining room, are located on the main floor. However, this building was also intended as a residence – if considering its monumental scale – with up to 54 bedrooms.

Key Figures:

- Area: 18,580 m2

- Length: 192 m

- Number of Rooms: 340

- Dome Height: 50.5 m

- Durbar Hall Diameter: 22.8 m

- Peak Workforce During Construction: 23,000 men and women, including 3,000 stone carvers.

Unfortunately, a rivalry arose between Lutyens and Baker, most famously surrounding the issue of elevation. According to Baker’s design, the axis leading to and located between the two ministerial office buildings was raised at a steep gradient before leveling off. As a result, when approaching the view from the east towards Rajpath and the Government Square, the Vice Regal Lodge’s visibility was severely compromised: nearing the end of the road, only the upper part of the dome was visible. Upon realizing this, Lutyens suggested that the slope be redone, but his request was rejected.

The grand staircase of the Vice Regal Lodge, with an opening above allowing sunlight during the day

and stargazing at night – an impressive layout suitable for grand occasions.

However, this did not detract from the overall achievements of the architects. When New Delhi was inaugurated in 1931, it brought many royal guests to tears in awe of the grandeur of the structure. Other planned capitals such as Chandigarh in Punjab by Le Corbusier, and Brasília designed by Lucio Costa and his architect Oscar Niemeyer, exist, but New Delhi remains in a class of its own, forever transcending the brief 14 years during which the lodge was magnificently utilized, marking the golden era of British rule in India.

West side of the Vice Regal Lodge, with a park designed according to Mughal principles.