We are all familiar with the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter, based on changes in weather, ecosystems, and daylight hours. However, these four seasons are too broad to accurately describe the nuances of weather and nature.

To mark the passage of time and understand changes throughout the year, many ancient East Asian cultures created calendars based on the sun and lunar cycles. The Hindu calendar has six seasons, the Chinese calendar includes 24 seasons, and the Japanese calendar is even divided into 72 seasons.

The Japanese calendar has four seasons similar to those we are familiar with in the West. However, each season is further divided into six parts, creating 24 sekki, with each part lasting about fifteen days. These intervals originally stem from the traditional lunar calendar of China, a timekeeping method where a year is divided according to the phases of the moon and the Earth’s orbit around the sun.

These seasons reflect the subtle rhythms of Japan’s ecosystem.

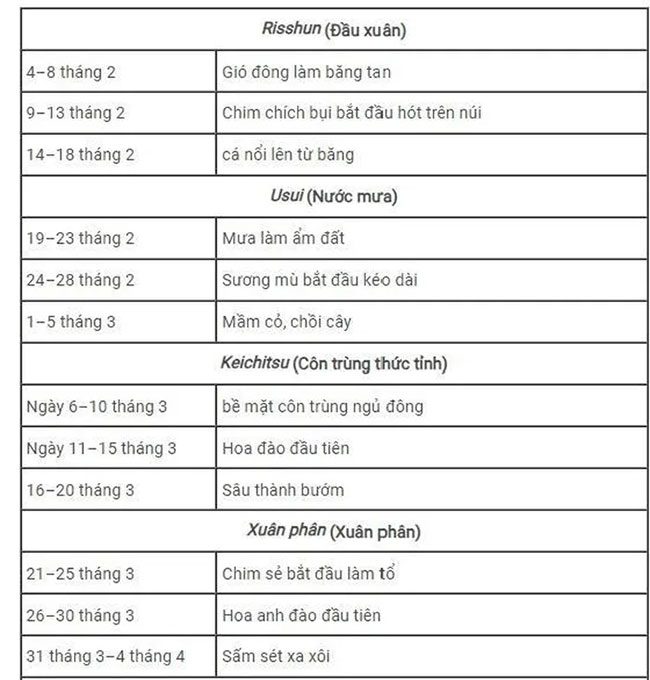

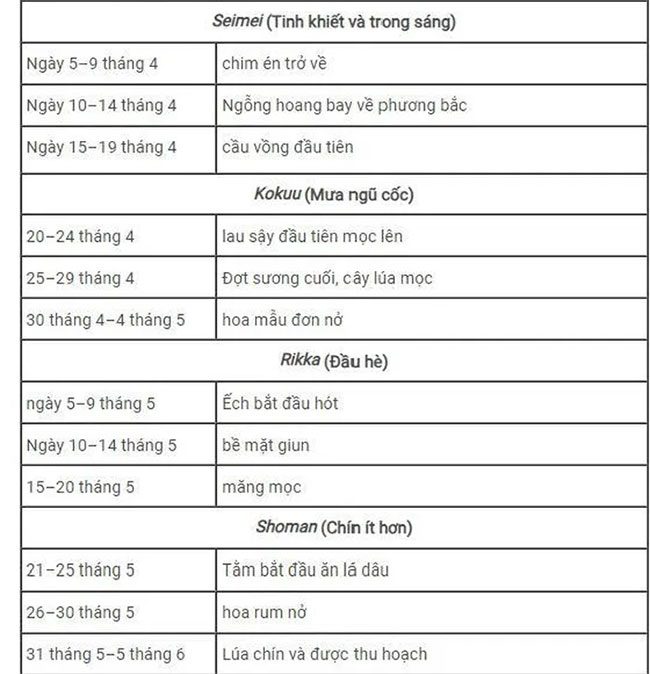

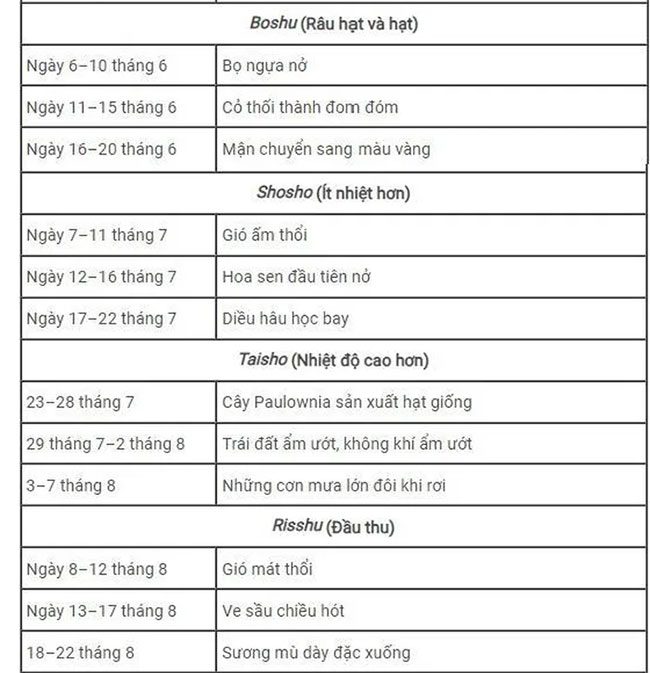

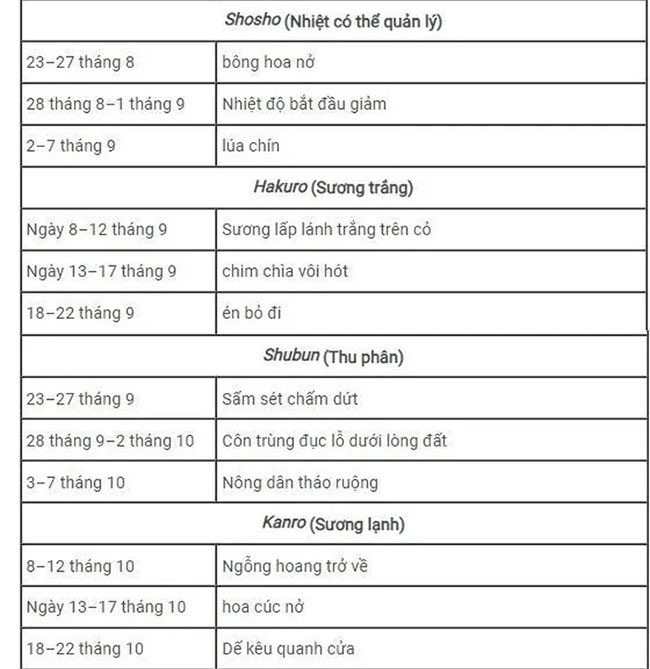

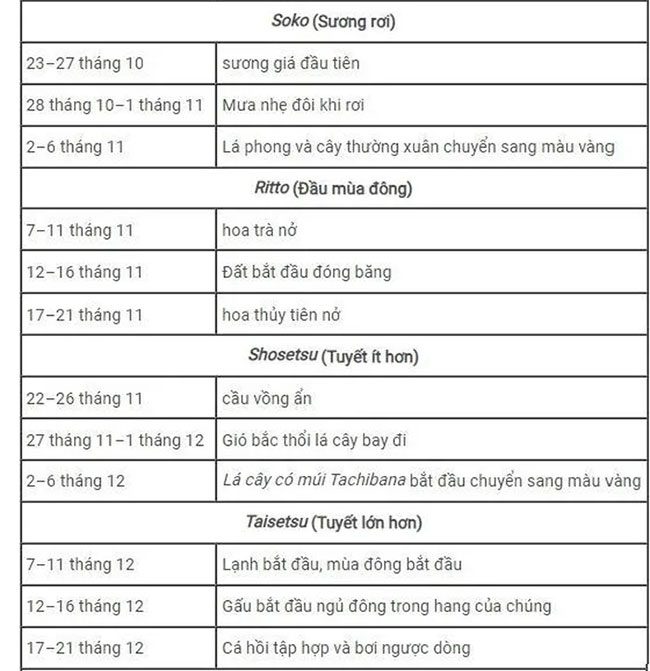

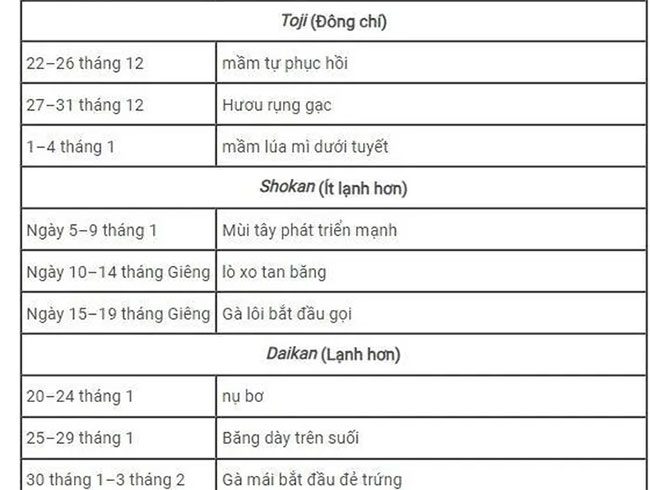

Each sekki is then further divided into three “ko,” resulting in a total of 72 ko. Each “ko” lasts about 5 days. These seasons reflect the delicate rhythms of Japan’s ecosystem, with each season correlating to specific natural events occurring at that time, such as the growth of bamboo shoots and the ripening of wheat.

“Every few days brings a new season, a new opportunity. Small enough to carry lightly. Big enough to care,” Quartz writes.

Mark Hovane explains the Japanese calendar in detail:

At the core of the four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter—are the equinoxes and solstices starting from shunbun (spring equinox), geshi (summer solstice), shubun (autumn equinox), and toji (winter solstice).

The beginning of each season is also observed in risshun (early spring), rikka (early summer), risshu (early autumn), and ritto (early winter). These markers account for 8 of the 24 seasonal points. The remaining 16 points are significantly influenced by weather and agricultural factors, such as rain, snow, and the progression of the agricultural cycle, and have distinctive names including usui (rainwater), keichitsu (insects awaken), shosho (controllable heat), or hakuro (white dew).

The breakdown of Japan’s seasons was originally imported from Korea in the mid-6th century. The names assigned to each sub-season were initially derived from climate and natural changes in northern China. As a result, there were minor adjustments when applied in the Japanese context.

In 1685, Shibukawa Shunkai, a court astronomer, revised these names, aligning them more accurately with the local climate and the nature of Japan. This revised calendar remained in use until 1873 when the Meiji government, in its pursuit of modernization, abolished the traditional calendar system and adopted the Gregorian calendar based on the Western solar system. However, many continued to maintain the use of the traditional calendar alongside the mandatory Gregorian calendar.