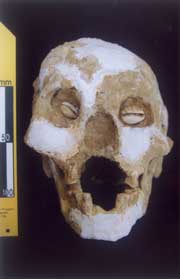

During the excavation of human remains at Phia Vài Cave, located in Cốc Ngận village, Xuân Tân commune, Na Hang district, Tuyên Quang province, Professor Nguyễn Lân Cường discovered a unique burial practice: placing sea shells in the eye sockets. According to Professor Nguyễn Lân Cường, this method of burial is the first of its kind identified in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

In November 2003, while conducting the “Project to Survey Historical and Cultural Sites in the Tuyên Quang Hydropower Reservoir Area,” scientific officials uncovered an important archaeological site – Phia Vài Cave, situated about 150 km north of Tuyên Quang town.

|

|

Unique burial practice discovered: Placing sea shells in the eye sockets. |

In early 2005, the Institute of Archaeology and the Tuyên Quang Museum conducted excavations at this cave. It is a beautiful limestone cave, with an entrance facing the Cốc Ngận stream, where prehistoric inhabitants utilized cobblestones to create tools. The cave is approximately 15 meters above the stream level, with its entrance facing directly west.

According to Dr. Trình Năng Chung and Dr. Nguyễn Gia Đối, the Phia Vài site features a mid-sized cave with stone niches to the north and a rock overhang to the south. The cave entrance is 35 meters wide, 11 meters deep, and the ceiling is 4 meters high. Unfortunately, large limestone blocks have collapsed from the ceiling, rendering a significant area inaccessible for excavation.

The archaeologists excavated two pits with a total area of 40m2 and discovered hundreds of artifacts, primarily crude chopper tools and flakes. These tools were made from cobblestones using common materials like basalt, litholite, and quartz.

Notably, during the excavation at Phia Vài, two burial sites and a hearth were uncovered. Based on the burial goods, the excavators believe that the first grave dates back to the metal age, approximately 3,000 years ago. The second grave, oriented northeast with the foot pointing southwest, contained stone tools and belongs to the stone age, dating back roughly 10,000 years.

Recognizing the significance of this discovery, the Director of the Tuyên Quang Museum, Quan Văn Dũng, decided to encase the second grave and hearth in plaster for preservation and future exhibition.

On May 6, 2006, we began cutting away the plaster casing from above the grave to collect soil samples for long-term preservation. Over the course of two weeks, my colleagues and I at the Tuyên Quang Museum gradually revealed the shape of this invaluable fossilized skeleton. The deceased was lying on their back with arms extended. Although the leg bones were almost entirely missing, based on the position of the talus and the left calcaneus, which were adjacent to the pelvis, we concluded that the deceased was buried in a flexed position – a common burial posture among the inhabitants of the Hoà Bình, Đa Bút, and Quỳnh Văn cultures… The shoulder girdle, scapula, ribs, and several finger bones remained well preserved.

Based on dental wear, the degree of cranial sutures, the structure of the greater sciatic notch, and the angle of the pelvic bones, we concluded that this was the remains of a woman, approximately 45 to 50 years old. Since the left arm bone was relatively intact, we estimated her height to be 1.56 meters. Notably, the skull rested on a stone ledge and exhibited a high degree of fossilization. In the upper jaw, the premolars, molars, and canines were relatively intact, while all incisors were missing. In the lower jaw, not only were all incisors absent, but also both canines, all left side premolars, and the first right premolar. It raises the question of whether the incisors were removed as part of a later custom among metal age inhabitants of the Phùng Nguyên culture in Mán Bạc, Xóm Rền, Đồng Đậu, which we have studied and published.

|

|

Associate Professor Dr. Nguyễn Lân Cường (left) and Director Quan Văn Dũng (right) handling the ancient human skeleton at Phia Vài. |

The excavators at Phia Vài Cave meticulously sifted through the excavated soil, making it unlikely that all incisors were lost. If this is indeed the case, the practice of tooth extraction may have originated in the stone age in Vietnam, although this burial custom was not as widespread as among ancient peoples of the Neolithic in China. This scientific hypothesis requires further investigation.

The skull is quite well preserved but has been compressed, resulting in flattening of the parietal and right occipital bones, causing the two mastoid processes and zygomatic arch to be misaligned from their original position. While using a small probe to gradually reveal the two sea shells nestled within the eye sockets of this woman, I noted that these were species scientifically named Cypraea arabica. The shell in the left eye socket measured 27.23 mm in length and 16 mm in width, while the shell in the right eye socket measured 21.61 mm in length and 13.13 mm in width, tilted slightly downwards. I squinted at the eye sockets of the woman from Phia Vài; it was strange, as if “she was squinting back at me…”

During her lifetime, these sea shells were used for trade, akin to currency today. At the time of burial, one shell was placed over each eye, so that as the flesh decomposed, the shells would settle into the eye sockets, serving as a substitute for the pupils.

Based on the positions of the arm bones, ribs, and pelvis, we believe this is the remains of a primary burial, not a reburial. Reflecting on the ancient skulls from the Hoà Bình culture that I have studied, such as Mái đá Điều, Mái đá Nước (Thanh Hóa), Động Can, Hang Chim, Hang Muối (Hòa Bình), and Mái đá Ngườm (Thái Nguyên), I have never encountered a case like this. Similar ancient skulls found in Southeast Asia also do not exhibit the practice of placing shells in the eye sockets.

To confirm, I called Dr. Ngô Thế Phong, a prominent archaeologist specializing in Southeast Asia, in Hanoi, and was pleased to find that he shared my assessment.

This burial practice reoccurred in the metal age when I studied an ancient skull of a man aged approximately 50 to 55 years found in Nga Văn, Nga Sơn district (Thanh Hóa) in April 2000. The only difference was that the skull and a section of the arm bone, along with a bronze spearhead, were reburied in an ancient bronze drum. The ancient people of Nga Sơn also placed items in the eye sockets, but instead of shells, they used two coins.

Currently, we are continuing our research on the remains from Phia Vài, and further conclusions regarding the anthropological characteristics of this woman will be forthcoming.