The town of Ny-Ålesund on Spitsbergen Island, part of Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, is often described as the cleanest air in the world. Located in a region considered a desert of the Arctic, the air in Ny-Ålesund is extremely dry and cold, often below freezing, causing every breath exhaled from a person’s mouth and nose to instantly turn into tiny ice crystals.

Ny-Ålesund is a tiny settlement located at the foot of Mount Zeppelinfjellet, with a population ranging from 45 in winter to 150 in summer. The town is the northernmost inhabited area in the world, situated about 1,231 km from the North Pole, according to the BBC.

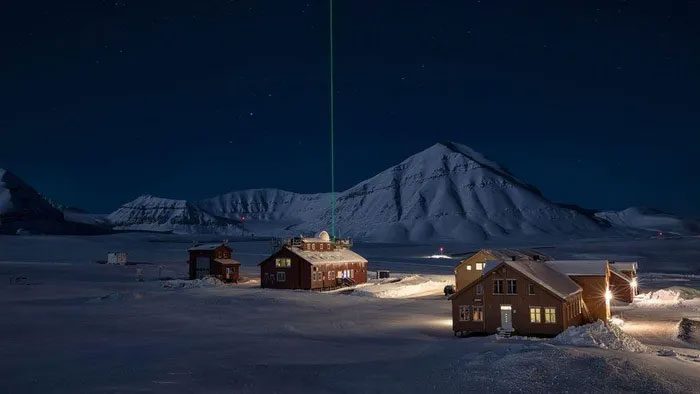

The town of Ny-Ålesund on Spitsbergen Island, part of the Svalbard archipelago. (Photo: Roger Goodwin).

No Wi-Fi, No Phones

From 1916 to 1962, Ny-Ålesund was a coal mining town. After a mining explosion that killed 21 people, the Norwegian government closed the coal mine. Since then, Ny-Ålesund has become a hub for scientific research.

In 1989, the Zeppelin research station was established on the slopes of Mount Zeppelinfjellet at an altitude of 472 meters, about 3 km from the town of Ny-Ålesund. This facility is used to monitor atmospheric pollution levels. In recent years, Zeppelin has played an essential role in measuring greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

The residents of Ny-Ålesund are primarily scientists from around the world, including France, Germany, the UK, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the USA, and China.

Each week, there are only two flights to Ny-Ålesund from Longyearbyen, another town in the Svalbard archipelago.

In Ny-Ålesund, there are about 30 buildings named after major cities like Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City. This serves as a reminder of the importance of maintaining friendly relations between nations in such a remote, harsh environment.

All mobile phones and Wi-Fi broadcasting devices are banned in Ny-Ålesund. To maintain the quietest environment possible, Ny-Ålesund also prohibits radio broadcasting. Anyone wishing to use radio transmission devices must obtain a special permit.

A laser beam used to measure air pollution levels in Ny-Ålesund. (Photo: Anna Filipova).

Extreme weather poses a challenge for anyone living and working in Ny-Ålesund. Temperatures frequently dip below freezing, with the coldest recorded temperature reaching -37.2 degrees Celsius. However, last March, temperatures hit a record high of 5.5 degrees Celsius, surpassing the previous record of 5 degrees Celsius set in 1976.

The Svalbard archipelago is the natural habitat of polar bears, which often venture near residential areas. Therefore, Ny-Ålesund residents must adhere to the rule of never locking building doors, allowing anyone to seek shelter in case of an encounter with a polar bear or during an emergency.

“Bears like to walk along rivers; they often travel the path from Ny-Ålesund to Zeppelin. At times, bears appear at the observation station, and we have to wait for them to pass before leaving the workplace,” said Christelle Guesnon, a researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

After work hours at 4:30 PM, residents of Ny-Ålesund mainly stay indoors. Due to the lack of communication devices, any community activities or social interactions in the evenings are typically scheduled in advance.

The town’s cafeteria is where people often gather for lunch or dinner, sharing stories about the auroras or polar bears they encounter.

Long-term workers in Ny-Ålesund report significant changes in the natural landscape, attributed to global warming.

“Warmer water from the Atlantic is increasingly changing the ecosystem of the fjord outside Ny-Ålesund. This affects polar bears, forcing them to alter their diet. Previously, bears only hunted seals on the ice. Now, we see many polar bears hunting eggs from bird nests and catching seals on land,” said Rune Jensen, Director of the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Pollution Begins to Infiltrate

Despite its clean air, signs indicate that air quality in Ny-Ålesund is being affected. Atmospheric currents sometimes carry polluted air from Europe and North America to Svalbard. Concerns also arise about new forms of pollution being brought to Svalbard by the wind.

“Zeppelin is located in a remote, pristine area, far from pollution sources. If pollution can be measured here, it means that pollution has spread globally,” said Ove Hermansen, an air quality expert at the Norwegian Research Institute.

Five days a week, a staff member from the Norwegian Polar Institute takes a cable car to Zeppelin to collect air samples and replace the filter of the equipment. Situated in a remote area above atmospheric layers that can trap pollutants emitted from the town of Ny-Ålesund, Zeppelin is an ideal location to create a comprehensive picture of the Earth’s atmospheric condition.

The cable car to the Zeppelin observation station. (Photo: Anna Filipova).

In addition to greenhouse gases, sensors at the observation station also measure chlorine-based gases like CFCs, heavy metals in the air, organic pollutants such as pesticides, and pollutants from fossil fuel combustion like nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and ultrafine particles.

“Observations at Zeppelin cover many issues. Environmental toxins have a significant impact on the Arctic, and measuring greenhouse gases and dust is particularly important to construct a global picture of the effects of climate change,” Hermansen stated.

The Zeppelin observatory can also provide early warnings about ongoing changes in the air.

For example, methane levels in the air at Zeppelin have increased since 2005, reaching a record high in 2019. There are growing concerns that human methane emissions threaten the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Scientists at Zeppelin are also observing increases in sulfate, ultrafine particles, and metals like nickel and vanadium in the air in Ny-Ålesund during the summer due to the rising number of tourist ships visiting the Arctic.

Industrial plants in Russia on the Kola Peninsula also emit heavy metals into the air, such as nickel, copper, and cobalt, with emissions sometimes reaching the Arctic during winter and spring.

Yet amidst the deluge of bad news, there are positive signals. Scientists have noted a reduction in heavy metal concentrations like lead and mercury due to stricter waste and industrial regulations in the EU, the USA, and Canada.

Efforts to reduce the use of phosphorous pesticides have also led to a decrease in harmful chemicals found in Arctic air.

Recently, scientists have begun to detect an increase in microplastic particles in snow samples collected at Zeppelin. Microplastics can travel great distances from their source via wind.

“Microplastics consist of durable polymers containing various chemical mixtures. We are very concerned that microplastics could bring harmful chemicals to the Arctic, which, on their own, wouldn’t travel that far, potentially destroying the fragile ecosystem here,” warned Dorte Herzke, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research.

Conservation and Research – A Noble Mission in the Arctic

With the goal of preserving the environment, Ny-Ålesund is not open to tourists. Only scientists and research station staff are allowed to visit. Photographer Anna Filipova is one of the few people granted special permission to document life and work in Ny-Ålesund.

The Kronebreen glacier.

This was her first time visiting this remote town to take photographs, and it is among the wildest and closest places to the Arctic she has ever worked.

Filipova remarked: “The Arctic is one of the most fascinating places on Earth, but it is also one of the most dangerous.” The continuous changes in the Arctic due to melting, regeneration, and disappearance have created an excellent environment for observing the impacts of climate change.

Although Ny-Ålesund is far from populated areas, it is not immune to the influence of air pollution from Europe and North America. Air pollution follows atmospheric currents, affecting even the cleanest areas in the world.

Filipova hopes that her photographs will help viewers understand the fragility of the Arctic. She highlighted a concerning example: the nearby Blomstrandhalvøya peninsula was once considered a peninsula in the 1980s, but within a decade, it became an island due to the shrinking Blomstadbreen glacier. Filipova’s images carry a powerful message about Arctic change and the urgent need to protect this region.