This is the world’s first reactor that will provide energy for Earth through nuclear fusion, similar to the Sun.

According to Euronews.com, at the center of Provence in France, some of the world’s leading scientists are laying the groundwork for the largest and most ambitious scientific experiment globally.

The scientists aim to create the largest nuclear fusion device in the world by harnessing energy from a reaction similar to that which powers the Sun.

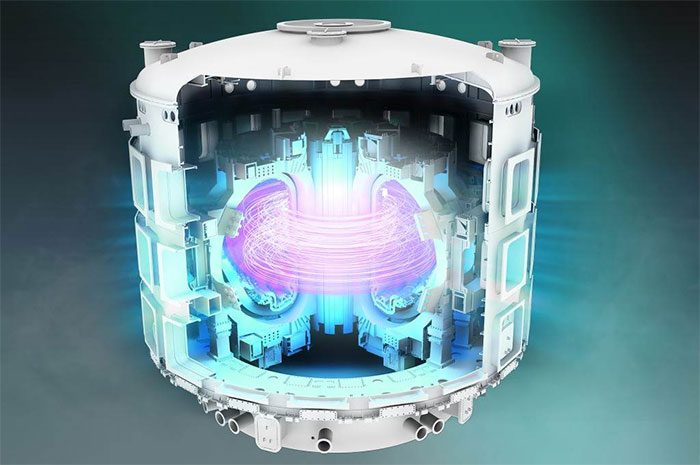

This image represents the concept of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) aimed at demonstrating the industrial feasibility of nuclear fusion energy. (Photo: iter.org).

Laban Coblentz, Communications Director of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), stated: “We are building the most complex device ever designed.”

The immediate mission is to demonstrate the feasibility of harnessing nuclear fusion on an industrial scale—the reaction that powers the Sun and stars.

To achieve this, the largest magnetic confinement vessel in the world, known as a tokamak, is being constructed in southern France to generate accumulated energy.

The ITER project agreement was officially signed by the United States, the EU, Russia, China, India, and South Korea in 2006 at the Élysée Palace in Paris.

Currently, more than 30 countries are collaborating in the effort to build the experimental device, which is expected to weigh 23,000 tons and withstand temperatures of up to 150 million degrees Celsius upon completion.

Mr. Coblentz indicated that, in a way, this is like a national laboratory, a large research facility, but it is actually a convergence of national laboratories from 35 countries.

How Does Nuclear Fusion Occur?

Nuclear fusion is the process in which two light atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, releasing a tremendous amount of energy.

In the case of the Sun, hydrogen atoms in its core are fused together due to immense gravitational forces.

Meanwhile, on Earth, two main methods are being explored to achieve fusion reactions.

Mr. Coblentz explained: “The first method involves firing lasers at a very small amount—about the size of a pepper grain—of two forms of hydrogen: deuterium and tritium. This way, a small amount of matter is converted into energy according to the formula E = mc² (E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum).”

ITER’s project focuses on a second viable method: Magnetic Confinement Fusion.

“In this case, we have a very large vessel, 800m³, and we place a very small amount of fuel—2 to 3 grams of deuterium and tritium—and we raise the temperature to 150 million degrees Celsius using various heating systems,” Mr. Coblentz said.

He further explained: “At that temperature, the velocity of these particles is so high that instead of repelling each other due to their positive charge, they combine and fuse. When they fuse, they release energy.”

In the tokamak, charged particles are trapped by magnetic fields, except for high-energy neutrons that are released and collide with the vessel walls, transferring heat and thus heating the water surrounding the tokamak. Theoretically, energy will be harnessed through steam generated to turn turbines.

Richard Pitts, head of ITER’s science department, further elaborated: “This is the legacy product of a long line of research devices.”

“The field of tokamak physics has been researched for about 70 years, since the first experiments were designed and built in Russia in the 1940s and 1950s,” Mr. Pitts noted.

According to Mr. Pitts, early tokamaks were small devices. Over time, they have become larger to produce fusion energy.

Overview of the ITER area. (Photo: iter.org).

Advantages of Fusion Energy

Nuclear power plants have been around since the 1950s, harnessing fission reactions, where atoms are split in reactors, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in the process.

Fission has the clear advantage of being a tested and proven method, with over 400 fission nuclear reactors currently operating worldwide.

However, despite nuclear disasters being rare in history, the catastrophic incident at reactor number 4 in Chernobyl in April 1986 serves as a strong reminder that they are never entirely without risk.

Moreover, fission reactors face challenges in safely managing large amounts of radioactive waste, often buried deep underground in geological repositories.

In contrast, ITER notes that a fusion power plant of similar scale would generate energy from much smaller amounts of fuel input, only a few grams of hydrogen.

Mr. Coblentz noted: “The safety efficiency is incomparable. We only need 2 to 3 grams of material. Moreover, the materials used in the fusion plant, deuterium and tritium, and the byproduct, non-radioactive helium and neutrons, are all fully harnessed. Therefore, there is no leftover, and the amount of residual radioactive material is extremely small.”

Challenges of the ITER Project

However, Mr. Coblentz emphasized that the challenge of fusion is that these nuclear reactors are still extremely difficult to construct.

“We are trying to heat something up to 150 million degrees Celsius. That is truly a hard feat to achieve,” he said.

Certainly, the ITER project has struggled with the complexity of this monumental task. The original timeline for the ITER project set 2025 as the date for the first plasma (ionized gas) launch, with full system operation marked for 2035.

However, component challenges and delays related to COVID-19 have led to a revised operational timeline and skyrocketing budgets. The initial estimated cost for the project was €5 billion, but it has risen to over €20 billion.

In terms of international collaboration, ITER also faces pressure from “headwinds” of geopolitical tensions among many participating nations.

Mr. Coblentz noted: “Clearly, the participating countries do not always share ideological alignments. Although they have committed to 40 years of collaboration, nothing is certain. There is never certainty that some conflict won’t arise.”

In conclusion, given the scale of the challenges posed by climate change, it is no surprise that scientists are racing to find a carbon-free energy source to power our world.

However, abundant fusion energy remains a long way off, and even ITER acknowledges that their project represents a long-term answer to energy concerns.

In response to the viewpoint that fusion energy will arrive too late to meaningfully help combat the climate crisis, Mr. Coblentz asserts that fusion energy could play a significant role in the future.

He stated: “If sea levels rise to the point where we need to consume energy to relocate cities, that is indeed a clear answer.”