This terrifying otter monster weighs up to 200 kg and was excavated from the Shungura and Usno formations in the Lower Omo Valley, Northwestern Ethiopia.

A research team led by Dr. Kevin Uno, a geochemist from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in the United States, has described this fearsome otter from fossil remains that include teeth and femur bones.

According to Sci-News, named Enhydriodon omoensis, this giant creature coexisted with our famous ancestor, the Australopithecus, between 3.5 and 2.5 million years ago.

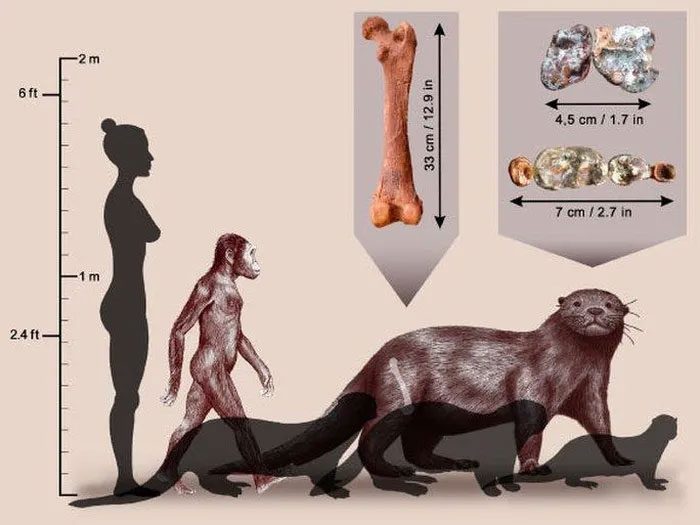

Portrait of the “monster” otter and Australopithecus, alongside shadows of other otter species and the shadow of modern humans – (Image: Sabine Riffaut / Camille Grohé / Palevoprim / CNRS – Université de Poitiers)

This is a new species belonging to the extinct genus Enhydriodon. This giant otter lineage inhabited the Eurasian and African continents during the Miocene epoch, approximately 6 to 2 million years ago.

Weighing up to 200 kg, with a body size comparable to that of a lion, Enhydriodon omoensis is the largest otter species ever found on Earth.

“Interestingly, aside from its gigantic size, isotopes in its teeth indicate that it was not semi-aquatic, unlike all modern otter species. It had a diet of terrestrial animals,” Dr. Uno stated.

Its relatives, the Enhydriodon otters, were all semi-aquatic animals that primarily consumed mollusks, catfish, and also preyed on other amphibians such as turtles and crocodiles, which were common in Africa’s freshwater environments.

Dr. Uno and his colleagues tested this idea by analyzing the stable oxygen and carbon isotopes in the enamel of Enhydriodon omoensis, finding that it was similar to that of terrestrial mammals, particularly large cats and hyenas from the Omo fossil deposits.

Thus, it seems that it did not favor fish, and while it was capable of hunting crocodiles and turtles on land, it may have supplemented its diet with a variety of terrestrial animals.

The Enhydriodon otters went extinct in Africa around the Plio-Pleistocene transition, along with many large, specialized carnivorous species.

The study has been published in the journal Comptes Rendus Palevol.