Analysis of Fragrances from Ancient Vessels in Egyptian Tombs Reveals They Contained Beeswax, Fruits, and Dried Fish for the Deceased.

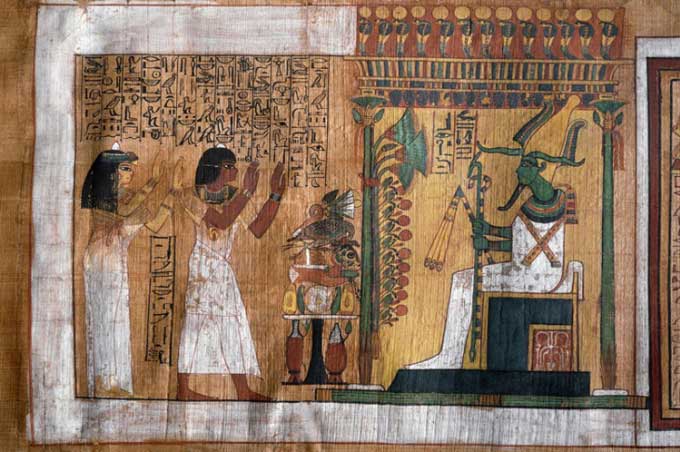

A painting in the tomb depicting Kha and Merit worshipping the god of the afterlife, Osiris. (Photo: Leemage/Corbis)

More than 3,400 years after the two ancient Egyptians were laid to rest, the food vessels meant to nourish their eternal souls continue to emit fragrances. A team of chemists and archaeologists conducted analyses of these scents to clearly identify the components within the vessels, as reported by Nature on April 1. The new study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The discovery of the intact tomb of architect Kha and his wife, Merit, in the Deir el-Medina cemetery near Luxor in 1906 marked a significant milestone for Egyptologists. Their tomb is the most complete non-royal tomb ever found in Egypt, revealing crucial information about how high-status individuals were treated after death.

Interestingly, at that time, the archaeologists who discovered the tomb did not open the sarcophagus or examine the contents of the sealed jars and vessels, even after they were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy. The contents of many of the jars remained a mystery, with only a few clues available. “When speaking with museum curators, we learned that there was a hint of fruity scents in the displayed jars,” said Ilaria Degano, a chemical analyst at the University of Pisa (Italy).

Degano and her colleagues placed several artifacts, including sealed jars and uncovered cups containing ancient decomposed food, into plastic bags for a few days to collect the volatile molecules that evaporated. Subsequently, the team employed mass spectrometry to identify the scent components of each sample.

They discovered aldehydes and long-chain hydrocarbons—indicators of beeswax, trimethylamine associated with dried fish, and other aldehydes commonly found in fruits. “Two-thirds of the artifacts yielded results. It was an exciting surprise,” Degano shared.

One of the jars analyzed using mass spectrometry. (Photo: J. La Nasa et al./Journal of Archaeological Science).

This new discovery will contribute to a larger project aimed at reanalyzing the tomb and creating a more comprehensive picture of burial customs for non-royals during the period when Kha and Merit lived, approximately 70 years before Tutankhamun ascended the throne.

This is not the first time that scents have revealed important information about ancient Egypt. In 2014, researchers extracted volatile molecules from linen dating back 5,000 to 6,300 years, used to wrap remains in several ancient Egyptian cemeteries. This confirmed the presence of embalming substances with antibacterial properties, suggesting that Egyptians experimented with embalming 1,500 years earlier than previously thought.

Scent analysis is a relatively unexplored field in archaeology, according to Stephen Buckley, an archaeologist and chemical analyst at the University of York (UK), who was part of the 2014 research team. “Archaeologists have often overlooked volatile substances, believing they would disappear from artifacts. But if you want to understand ancient Egyptians, you really want to delve into the world of scents,” he stated.