The excavation results discovered by Belgian and Greek archaeologists at a site on the island of Cyprus are truly impressive, shedding further light on the end of the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean and the mysterious “Sea Peoples.”

This is a genuine treasure that archaeologists from Ghent University (UGent) and KU Leuven (KLeuven), in collaboration with Greek partners, have uncovered on Cyprus. The treasure consists of gold, silver, copper, and plaster, and most importantly, it provides a wealth of data that clarifies the complex history of the late Bronze Age, around 1200 BC.

Belgian and Greek archaeologists at the excavation site in southeastern Cyprus, discovering numerous artifacts from the Bronze Age. (Photo: D.R)

This period is referred to as the “years of crisis,” when the Mycenaean palaces of Greece (the final phase of the Bronze Age in Greece, lasting from about 1750 BC to 1050 BC) were destroyed, Troy was burned, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia collapsed, and many kingdoms along the coasts of Syria and Lebanon fell. At the same time, Egypt was attacked by a mysterious coalition of foreign peoples known as the “Sea Peoples.”

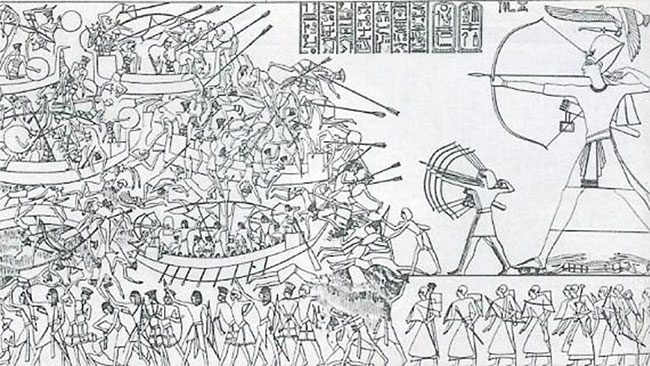

These tribes are often blamed for causing all the devastation. However, since the initial images of them were discovered on the walls of the tomb of Pharaoh Ramses III (1193-1163 BC) at Medinet Habu in Egypt, discussions have arisen about the identity and origins of the Sea Peoples.

Continuous Discoveries

Today, it appears that Cyprus played a significant role in this history. From 2014 to 2021, an expedition involving Professor Joachim Bretschneider from Ghent University (UGent), Professor Jan Driessen from KU Leuven (KLeuven), and Dr. A. Kanta from the Mediterranean Archaeological Society, in collaboration with researchers from the Cyprus Institute and Vienna, was conducted on a large hill near the village of Pyla, on the southeastern coast of Cyprus.

Peleset warriors in the Medinet Habu relief. (Photo: D.R)

This site is not far from significant areas of the Late Bronze Age, such as Enkomi, Kition, and Hala Sultan Teke. Cyprus is less than 200 km from the Syrian coast and less than 400 km from Egypt. These relatively short distances for shipping are crucial for understanding what transpired here.

In the 1980s, the renowned Cypriot archaeologist Vasos Karageorghis made some intriguing discoveries at Pyla. More recently, two Cypro-Minoan inscribed tablets were found, clearly having been stored. However, the Cypro-Minoan script has yet to be deciphered.

Since the initiation of new excavations in 2014 by the Belgian-Greek archaeological team, many significant discoveries have been made. It is evident that the entire hill is densely populated with nearly identical houses in size and design; they are surrounded by a terraced wall, flanked by towers and fortifications. The entire layout is meticulously planned and exhibits a military appearance. What is most surprising is that this site was suddenly abandoned, and all objects remained in their original positions—ceramic, copper, and stone artifacts were found throughout this complex, with no signs of later disturbance.

Even more astonishing is the observation that just before the inhabitants left, valuable items were hidden in pits and vaults. For example, Joachim Bretschneider’s team (UGent) discovered a plaster egg in a deep well. An “egg,” when opened, contained a gold plate weighing 472 grams, which is currently on display at the Larnaca Museum. Jan Driessen’s team uncovered a large plaster vase, decorated with lotus flowers, which was clearly brought from Egypt. It contained jewelry made of copper, ivory, and stone. Many of these hidden treasures have been discovered throughout the hill, a clear indication of an impending threat.

Pirate Spoils

For archaeologist Joachim Bretschneider, the Pyla site is essential for understanding the history of the late Bronze Age, as its brief period coincides with the time the Sea Peoples were active in the eastern Mediterranean before being defeated by Ramses III in a battle that took place in the eighth year of his reign, possibly around 1186 BC. These findings are highly significant.

Since the initiation of new excavations in 2014 by the Belgian-Greek archaeological team, many important discoveries have been made. (Photo: D.R)

Thus, the question arises: could the Pyla site have sheltered the Sea Peoples, from which they launched pirate attacks against the surrounding areas? Their fortified houses could easily accommodate around 7,000 people, enough to embark warriors on dozens of ships, departing from a hidden inland port at the foot of the hill. The attacks and plundering by pirates could explain the presence of many valuable possessions found in all these houses—houses where, to date, no traces of a palace or temple have been found. These goods could of course be the result of trade exchanges, but items obtained from commerce are often found in a few houses, not scattered throughout.

But who were the Sea Peoples? Professor Bretschneider noted that the Pyla site has yielded many strange artifacts: Canaanite jars, Mycenaean and Minoan pottery, Egyptian plaster vases, Sardinian jars, jewelry from Ugarit and the Hittites, and so on, not to mention many locally produced or imitated vases. Thus, it is likely that the inhabitants were formed from a mixture of various Mediterranean peoples.

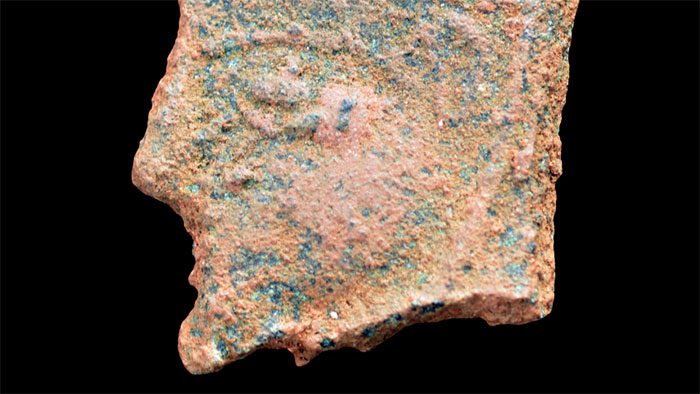

New excavations also uncovered jars shaped like ships and images of warriors similar to those depicted in the reliefs of the Sea Peoples at the temple of Ramesses in Medinet Habu. A small bronze head, found in the latest excavation campaign, represents a man wearing a feathered headdress. According to Jan Driessen, if this fragment could belong to a representation of a mythical creature—a sphinx—then “the resemblance to the feathered headdresses worn by the Peleset warriors in the Medinet Habu reliefs is also evident.”

These Peleset warriors are often considered the ancestors of the Philistines. After being defeated by Ramses III, they settled in the coastal region of present-day Israel, in the cities of Gaza, Ashkelon, Gath, Ashdod, and Ekron (Pentapolis). The origins of the Philistines have also been widely debated, as according to the Bible, they came from Kapthor, which is believed to be the island of Crete. DNA analysis of Philistine graves also shows they have origins in Southern Europe and could thus be from Greece, Crete, or Cyprus.

Today, Egyptologists, such as Professor Pierre Grandet, argue that the term for Egypt (Egype) commonly transliterated as “Peleset” should instead be read as “Poulasti.” Jan Driessen points out the phonetic similarity between Poulasti and the Mycenaean Greek Pula-Wasti, “the city of Pyla.” Could Pyla actually be the birthplace of the Poulasti tribe? Did they take the name Pyla from Greece, where the names Pyla and Pylos exist in Messenia (western Peloponnese)? These are hypotheses that tantalize archaeologists.

A small bronze head found in excavation campaigns depicting a man wearing a feathered headdress. (Photo: D.R).

The Peoples of the Earth

Joachim Bretschneider states that if the connection between the Pyla site and the Sea Peoples can be proven, then after plundering the surrounding areas, the “Pylians” may have temporarily abandoned their strongholds (hiding their valuables) and attacked Egypt, where they were ultimately defeated. Ramses III prevented them from returning to Cyprus and resettled them in what would later be known as Philistia. From the “Sea Peoples,” they would later become the “Peoples of the Land”…

Were the Sea Peoples solely responsible for the widespread devastation across the eastern Mediterranean? Probably not. In his book, “1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed,” American author Eric Cline presented and considered a range of hypotheses explaining this generalized collapse. These include global warming, followed by drought and famine, earthquakes, civil wars, and the mass movement of population groups fleeing their homelands, among others. However, there is no scientific consensus on the matter.

Therefore, it is very likely that the Maritime Peoples were merely a part of the broader crisis factors, which included a series of significant climate change events in various regions. This phenomenon led to issues with food supply and ongoing environmental migration. Consequently, the end of the Bronze Age marked the conclusion of the snowball effect or the collapse of the dominoes—essentially, a butterfly effect. However, the location of Pyla makes it a bit easier to reconstruct history.