Scientists have extracted DNA from eight of the nine hammerhead shark species and used it to examine their relationships. The results left them astonished.

Hammerhead sharks are known for their strange appearance. They look as if someone has grabbed their skull at the eye sockets and stretched it out to the sides, while the rest of their body resembles that of a typical shark.

You might wonder – what are the advantages of having this hammer-shaped head? And how did hammerhead sharks acquire such a distinctive “maritime rogue” appearance?

Gavin Naylor is a scientist who has been studying sharks for nearly 30 years. The answers to some of these questions surprised even him.

Hammerhead sharks are known for their strange appearance.

Benefits of the Hammer

Scientists believe that hammerhead sharks have three main advantages.

The first is enhanced vision. For example, if your eyes are facing in two opposite directions, like towards your ears, you will have a much wider field of view. Each eye sees different parts of the world, allowing you to perceive more of your surroundings. However, it becomes difficult to gauge how far apart things are.

The second advantage is that to compensate for this trade-off, hammerhead sharks possess special sensory organs known as Lorenzini ampullae, which are scattered along the underside of their hammer. These pore-like organs can detect electric charges.

These pores essentially function like a metal detector, sensing and locating prey buried under the sand on the ocean floor. While sharks generally have these sensory organs, hammerhead sharks possess more of them. The greater the distance between these sensory organs on the extended head of the hammer, the more accurately they can pinpoint the location of food.

Finally, scientists believe the hammer helps sharks turn more quickly while swimming. If you’ve ever walked in strong winds with an umbrella or flown in a plane, you know how large surfaces can move powerfully. If you are a hammerhead shark and your intended dinner swims by quickly, you can turn your head to catch it faster than other sharks can.

Hammerhead Shark Lineage

It would be wonderful if we could examine fossils and trace the evolutionary development of hammerhead sharks over time. Unfortunately, the fossil records of hammerhead sharks consist almost entirely of their teeth. This is because sharks do not have bones; their bodies are made of cartilage, similar to our ears and noses. Cartilage breaks down much faster than teeth or bones, making it rare for it to fossilize. And tooth fossils don’t tell us much about the evolution of the hammerhead skull.

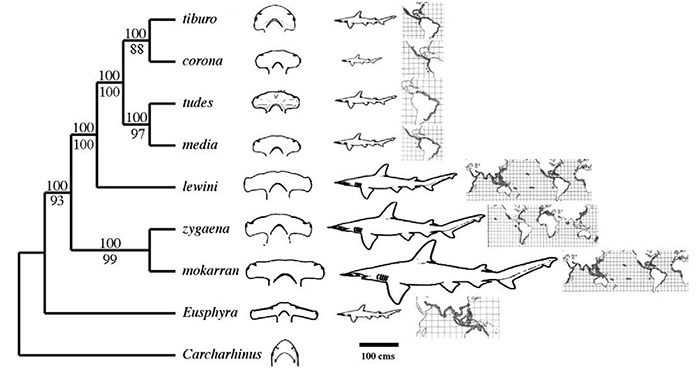

There are nine different species of hammerhead sharks swimming in today’s oceans. They vary in both size and shape of their heads. Some have heads that are very wide relative to their bodies, including the Great Hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran), Smooth Hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena), Scalloped Hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini), and Carolina Hammerhead (Sphyrna gilberti).

Other species have smaller hammers in proportion to their bodies, such as the Bonnethead Shark (Sphyrna tiburo), Spoonhead Shark (Sphyrna media), Small-eyed Hammerhead (Sphyrna tudes), and Winghead Shark (Sphyrna corona).

Scientists have long believed that the earliest hammerhead sharks did not have hammers in the strictest sense, but over time, some species gradually evolved larger hammers. We think that the different hammerhead shark species alive today are snapshots from various points in their evolutionary history – with the Small Hammerhead being the oldest in the lineage and the Great Hammerhead the most recently evolved.

Since we do not have fossils to examine, scientists explored this idea by using DNA. DNA is the genetic material found in cells that carries information about the shape and function of a living organism. It can also be used to see how living organisms are related.

Scientists extracted DNA from eight of the nine hammerhead shark species and used it to examine their relationships. The results were not what we expected. It turns out that the older species have larger hammers while the newer species have smaller ones.

Where Will Hammers Evolve Next?

It turns out that the older species have larger hammers while the newer species have smaller ones.

When scientists think about evolution, we often assume that living organisms change gradually, slowly adjusting to better take advantage of their environment. This process is known as natural selection. But it does not always work that way, as the evolution of the hammer of the hammerhead shark has shown.

Sometimes, an animal may be born with a genetic defect that turns out to be beneficial for its survival. As long as the abnormality can survive and the animal can mate, that trait may be passed on. Gavin Naylor believes that is exactly what happened with hammerhead sharks.

The earliest branching hammerhead species is the Scalloped Hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini), which has one of the widest heads. Over time, natural selection has actually reduced the size of the hammer. It turns out that the most recent hammerhead species is the Bonnethead (Sphyrna tiburo), which has the smallest hammer of all.

|

Hammerhead sharks are the common name for species in the family Sphyrnidae, within the order Carcharhiniformes in the subclass Elasmobranchii, class Chondrichthyes. These species are easily recognizable by their unique cartilaginous structure at the flattened head, which extends out to the sides forming a shape known as a “cephalofoil”. Hammerhead sharks belong to two genera, Eusphyra and Sphyrna, with most species classified under the genus Sphyrna, while the genus Eusphyra contains only one species, the Winghead Shark (Eusphyra blochii). The habitat of hammerhead sharks is warm marine areas along coastlines and continental shelves, most commonly found in the waters of Malpelo Island (Colombia), Cocos Island (Costa Rica), the Hawaiian Islands (USA), and Southern and East Africa. Hammerhead sharks reproduce only once a year. Males will bite females until they agree to mate. Each time they give birth, hammerhead sharks produce about 12 to 15 pups (the non-grooved hammerhead can give birth to 20 to 40 pups). The young hammerhead sharks do not receive parental care; they must swim together towards warmer waters until they grow large enough to hunt individually. The diet of hammerhead sharks includes fish, squid, octopus, crustaceans, and even relatives like stingrays. Their unique head is used as a weapon while hunting. Hammerhead sharks use their heads to disable the defensive capabilities of stingrays, causing them to weaken. The larger and more aggressive species is the Great Hammerhead, which is an opportunistic feeder that includes all squid, octopus, and may even cannibalize other hammerhead sharks and their young. According to the International Shark Attack File, humans are the subject of 17 recorded unprovoked attacks by hammerhead sharks of the genus Sphyrna since 1580 AD. No fatalities have been reported. Great Hammerheads and Scalloped Hammerheads are listed as endangered in the 2008 Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), while Small-eyed Hammerheads are listed as vulnerable. This status is a result of overfishing and the demand for their fins, a costly delicacy. |