The underwater mountain range is located at a depth of about 4,000 meters, formed under the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a current that affects sea-level rise.

A team of scientists aboard the research vessel Investigator discovered the underwater mountain range during an expedition in the Southern Ocean, organized by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), as reported by Newsweek on December 18. The initial goal was to study the Antarctic Circumpolar Current – the strongest ocean current in the world – to understand how it contributes to rising sea levels. Specifically, they examined how the current transmits heat toward Antarctica.

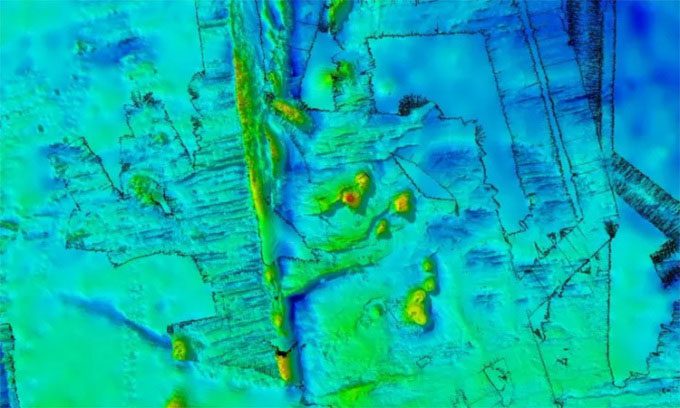

The newly mapped area with underwater mountains. (Photo: Focus/CSIRO).

During the expedition, the scientists scanned an unmapped marine area stretching 370 km west of Macquarie Island. They found that beneath the powerful swirling current, at a depth of about 4,000 meters below the surface between Tasmania and Antarctica, lies an underwater mountain range.

This remarkable ancient underwater mountain range consists of 8 inactive underwater volcanoes with peaks approximately 1,500 meters high, according to CSIRO geophysicist Chris Yule. One of the mountains even features a double caldera.

This area is located near the Macquarie Ridge Fault, where tectonic activity is still ongoing. The mountains likely formed from a “hotspot” beneath the Earth’s crust around 20 million years ago. Discoveries like this are crucial for enhancing our understanding of ocean dynamics, according to Helen Phillips, a member of the expedition team.

During the research, the team utilized a new satellite developed by NASA and the French National Centre for Space Studies (CNES). This allowed them to scan seabed images with high resolution.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current flows clockwise, from west to east, around this continent. It is not only the strongest ocean current in the world but also the only current that connects all the oceans globally. Therefore, studying this current is particularly important, helping scientists understand what is happening to the oceans due to climate change.

“The ocean absorbs over 90% of the heat from global warming and about 25% of human CO2 emissions. We are working at a ‘gateway’ where heat is transmitted to Antarctica, contributing to ice melt and rising sea levels. We need to understand how this gateway operates, how much heat is transmitted, and how this may change in the future,” said Benoit Legresy, the lead scientist of the expedition.