New research indicates that the Atlantic Ocean currents are weakening, disrupting tropical monsoon patterns for at least 100 years, resulting in shorter rainy seasons and more storms.

The Atlantic currents, which transport heat to the Northern Hemisphere, may be coming to a halt due to climate change. A new study from the Technical University of Munich in Germany suggests that this will lead to disruptions in the tropical monsoon system for at least a century.

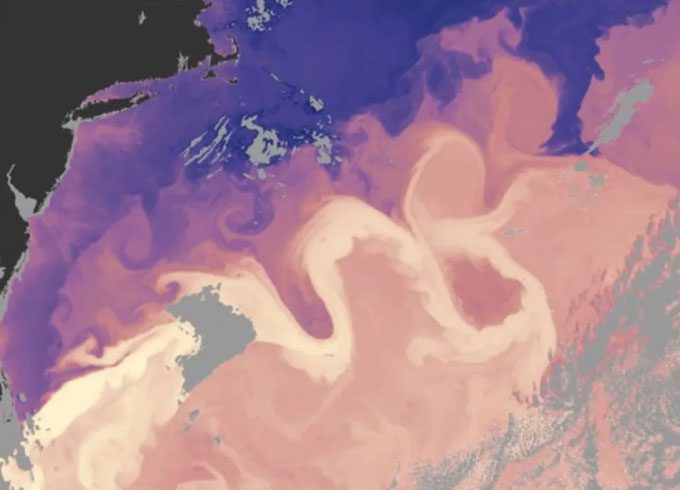

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a massive current system, including the Gulf Stream, that pumps heat and salt from the South Atlantic to the North Atlantic. Maya Ben-Yami, a climate researcher specializing in climate tipping points at the Technical University of Munich and the lead author of the study, compares AMOC to a ventilation fan. Thus, the collapse of AMOC could significantly impact heat transport in the Earth’s system. The collapse of AMOC is likely to cause global climate changes, particularly affecting the Northern Hemisphere and tropical monsoon regions, according to Ben-Yami. Researchers have long suspected that the weakening of AMOC would disrupt the tropical monsoon system, but the new study provides a much clearer picture of what may happen.

The Gulf Stream current provides heat and salt to the North Atlantic (light pink) based on satellite data recording sea surface temperatures. (Photo: NASA).

Global warming threatens AMOC due to melting ice and glaciers, leading to freshwater flowing into the North Atlantic. This dilutes the salinity of the upper water layers and prevents them from sinking to the ocean floor, where they typically drive the southward flow.

Tropical monsoons occur in a narrow band of low-pressure atmospheric conditions surrounding the Earth near the equator. Trade winds from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres blow into this band, known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), resulting in heavy rains and storms during certain months of the year.

Ben-Yami states that the ITCZ is linked to ocean temperatures and, therefore, is connected to AMOC. The ITCZ forms from warm air rising from the sea, so it develops over the hottest areas on Earth, fluctuating seasonally along the equator.

“As the Earth is tilted, the warmest areas shift up and down. Therefore, the vast rainband around the planet also shifts up and down,” Ben-Yami explains.

If AMOC slows down or stops, it will not provide the same amount of heat to the Northern Hemisphere, meaning sea temperatures there will be colder. If the Northern Hemisphere cools, the hottest areas on Earth will shift further south. The ITCZ will follow, still fluctuating but closer to the South Pole, bringing along significant rainfall. “Currently, we have areas accustomed to very heavy rainfall during the rainy season,” she said, adding that this may not last as the entire system shifts southward.

To simulate the impact of AMOC collapse on tropical monsoons, Ben-Yami and her colleagues used eight modern climate models to conduct experiments known as “watering.” She explained that watering is equivalent to pouring freshwater into the North Atlantic to model the effects of melting ice, and the researchers conducted this over a simulation period of 50 years until AMOC declined. The research team published their findings on September 3 in the journal Earth’s Future.

The models indicate that the collapse of AMOC will disrupt the tropical monsoon system globally. In West Africa, India, and East Asia, the rainy season becomes shorter and less intense as the ITCZ shifts southward. Ben-Yami noted that these results align with previous predictions, but the climate changes in South America surprised the researchers.

Heavy rains during the monsoon can cause floods and damage. The photo shows residents of Hoa Binh village, Trung Gia commune, Soc Son district, Hanoi, struggling as floodwaters inundate their yard by about 2 meters. (Photo: Nguyen Dong).

Ben-Yami mentioned, “The more interesting results are for the Amazon.” There, the model predicts a significant delay in the annual monsoon as well as a reduction in rainfall. “A three-month delay in the rainy season could be very detrimental to the ecosystem,” she said.

When AMOC collapsed in the models, the researchers turned off the watering simulation and observed the system for another 100 years. Despite the absence of freshwater inflow, the tropical monsoon did not return to its original state, indicating that the impact of AMOC collapse is irreversible for at least a century.

Ben-Yami stated, “The impacts we present in this paper are irreversible for 100 years,” adding that this is a long time frame.

Previously, a study by author Johannes Lohmann from the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen warned that AMOC could reach a “tipping point” much earlier than expected, and its consequences could be catastrophic.

Accordingly, the increase in freshwater from melting ice in Greenland is at alarming levels and poses a major threat to AMOC. If this current system completely stops, tropical monsoon patterns will change, rainfall in the Northern Hemisphere will decrease, and the North Atlantic will experience more storms. It also raises concerns about other climate tipping points, such as the collapse of ice sheets at both poles or the drying out of tropical rainforests in the Amazon.