- Construction Period: 1563 – 1584

- Location: Northwest of Madrid, Spain

The Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, mentioned by the metaphysical poet John Donne in his 1611 poem “Funeral Elegie”, serves as an embodiment of vast scale, continually captivating visitors with its sheer size. At first glance, one is astonished that this monumental estate was conceived, undertaken, and completed within the lifetime of its founder, King Philip II of Spain.

We are fortunate to have a comprehensive contemporary description of the Escorial Monastery by the learned cleric Jose Siguenza, published in 1605, who later became the abbot of the monastery.

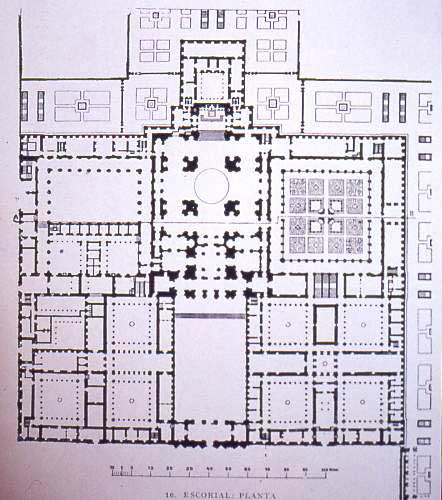

Blueprint of Escorial Monastery (Image: unav)

Concept

King Philip II’s initial plan was to construct a mausoleum worthy of his father, Emperor Charles V, and for himself and his descendants. This mausoleum needed to be situated within a grand monastery where continuous prayers could be offered for the soul of the deceased king. The intention was to dedicate it to St. Lawrence, a Spanish martyr whom Philip revered since childhood, as a thanksgiving for Spain’s victory over the French at St. Quentin in 1557 on the feast day of St. Lawrence, August 10. However, the often-repeated story that the floor plan of the Escorial Monastery was inspired by the iron bed of the martyr St. Lawrence is merely a myth.

|

Marble Tomb (Image: lunapark) |

Initially, the Escorial Monastery served as both a mausoleum and a monastery, but within the rectangular layout, it was designed to incorporate a range of other functions. About a quarter of the floor plan (on the East and Northeast sides) was allocated for the royal palace. Typically located in Madrid, the royal court often retreated to Escorial for its cooler weather, as it stands at an altitude of 1,125 meters, making it a sensible choice given its proximity to the small village of El Escorial at the foot of the Sierra de Guadarrama.

Another reason for choosing this location was the availability of educational and medical facilities. The Council of Trent (1545 – 1563) suggested that each major religious institution should establish a university, teaching both laypeople and training Christian clergy. These facilities were situated in the Northwest section of the complex, while the Southwest corner housed guest rooms, infirmaries, and rest areas, along with a pharmacy capable of providing substantial medical supplies.

Design and Construction

The architect chosen by King Philip II was Juan Bautista de Toledo, who had served for 11 years as an architect and engineer in the royal court of the Viceroy of Naples and previously worked as the second architect after Michelangelo on St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The final plan was approved by the king in 1562, mandating construction according to the geometric system of Vitruvius, which involves equilateral triangles inscribed within a circle. A detailed study of the floor plan indicates a formation of numerous internal divisions; Juan Bautista employed a module of 1/6 of 100, approximately 5 meters.

The outlined plan consists of a main rectangular building measuring 204 meters long (North-South) and 160 meters wide (East-West), featuring projections toward the East (the king’s apartments) and Southwest (the rest area). Surrounding the main structure and integrated into the design are terraced lands creating pathways or gardens approximately 30 meters wide. The original design by Juan Bautista envisioned 10 towers around the perimeter of the building, but this number was reduced to 6, with 1 tower at each corner and 2 towers along the sides following design changes in 1563 and 1564.

Aerial view of Escorial showing the multifunctional complex from the west.

The layout from Juan Bautista in 1562 remained unchanged, but he had to modify the elevation twice. The first change occurred in 1563, shortly after construction began, when the church design was altered to accommodate a radical proposal from an Italian consulting architect, Francesco Paciotto of Urbino. The second change in 1564 required raising the height of the western half of the building by an additional floor to provide extra accommodation when Philip II agreed to increase the number of clergy from 50 to 100.

Key Measurements:

- Main building: 204 x 160m

- Terraced land: 30m wide (60m towards the west)

- Number of towers: 6

The sudden death of Juan Bautista in 1567 shocked everyone. However, the foundations were completed, and many walls were under construction. The architect left behind a wooden model and complete drawings that had been approved by the king. Juan de Herrera (1530 – 1597) took over some additional phases of work. He was a regular soldier who, while serving in 1564, assisted Juan Bautista as a design draftsman. After Juan Bautista’s death, Herrera retained control of the design office, thus likely influencing the construction process.

|

| Panorama of Escorial Monastery from the southwest, with a square pond in the foreground and stone arches designed to contrast with the upper wall, which has 259 windows (Image: umwelt-verkehr) |

Recently, he has been recognized for redesigning significant details of the Escorial Monastery, including the church and the grand staircase within the monastery, but these estimates conflict with statements from José de Siguenza, who certainly must have known what transpired. He clearly stated that the church’s construction had to follow the design by Francesco Paciotto of Bergamo, and through other evidence, we know he was an experienced staircase designer. However, Herrera certainly redesigned the roofing, which is, in fact, the only design contribution he personally acknowledged.

At various points during the 21 years of construction, many craftsmen and laborers were directly hired by the monastery under contract, while at other times, specific construction phases were put to tender, both methods receiving mixed reviews.

All exterior walls were completed and clad in locally quarried granite – a gray Guadarrama stone that harmonizes with the overall layout. Transporting the stone from the quarry to the site using ox-drawn carts was highly efficient; each cart pulled by a pair of oxen required a total of 200 trips to complete the delivery, with a senior cleric assigned to provide medical care for them.

The Escorial style, decided by the king, is a style of the later Renaissance period, combined with influences from various architects in Italy, such as Giorgio Vasari and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola. Contemporaries like Siguenza viewed the style as Vitruvian, and it is certain that the structure contains numerous elements related to principles from ancient Roman architectural teachings. The competition to build in the classical style was the main ambition of patrons and architects during the Renaissance; by early 1578, the Escorial Monastery was being referred to as the octavo molagro or Eighth Wonder of the World, surpassing the other seven wonders.

The exterior facade of the main building has been criticized for its unattractive appearance; however, this does not acknowledge the architect’s intention to create a contrast between the ordinary walls and the adjacent spaces – the terraced gardens with fruit trees and the park below, located to the south and east, with the west and north featuring extensive terraced land that extends the alignment of the walls at the facade into a third dimension through patterned paving. Similarly, the typical elevation of the courtyard contrasts and thus highlights the richly decorated interiors of the structure.

The sanctuary and main altar of the Escorial church viewed from the intersection. (Image: lunapark)

Interior Decoration

Philip II was highly invested in the decorative paintings and sculptures of the interior of the Escorial monastery, as well as in its architectural design. The frescoes feature comprehensive themes painted by Luca Cambiaso and Pellegrino Pellegrini (Tibaldi) within the church, monastery, and main library. Many details on the altars were commissioned from Italian and Spanish artists, including the image of St. Lawrence by Titian and St. Maurice by El Greco. However, the work by El Greco was removed by the king for not aligning with the more inspirational representation of the Spanish artist Nararrete; the details of El Greco’s altar did not evoke a sense of piety. Philip II’s successors continued his tradition of illustrating the monastery’s design, which was reflected in the monks’ meeting rooms, featuring works by Tintoretto, Rubens, and Velázquez.

Every detail of the design and decoration of the Escorial monastery had to be consulted and approved by Philip II. He even participated in discussions about which types of trees to plant in the gardens, ensuring that the selected trees would flourish by the time the project was completed. Construction was one of his primary concerns, at least since he was 14 years old when he first began studying architectural texts. Some described him as someone who should have been an architect. Among his titles was King of Jerusalem, which meant he was considered the successor to six kings of Israel, with gigantic statues overlooking the entrance courtyard known as the Patio de los Reyes.

Panorama of the Escorial monastery (Photo: faculty-staff)