On the Friday before Easter in Huanchaquito, a coastal village in northern Peru, the thumping beats of dance music drifted from cafes just a few hundred feet from the water’s edge. The bass rhythm of the song pulsed like a heart beating with anticipation.

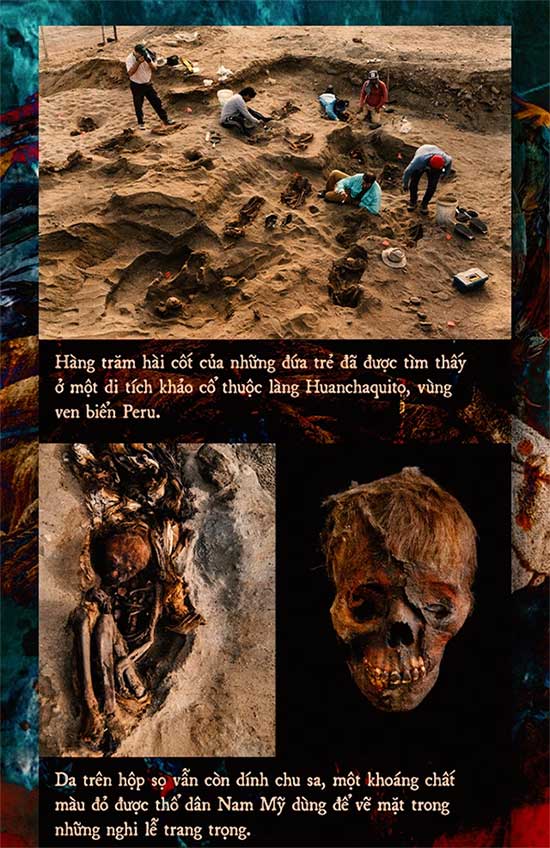

Amidst this, the sound of shovels “chúp” “chúp” was heard from a group of local workers in a vacant lot littered with garbage. Here, they were assisting archaeologists in uncovering a site buried beneath sand, rocks, plastic bottles, and even shell casings.

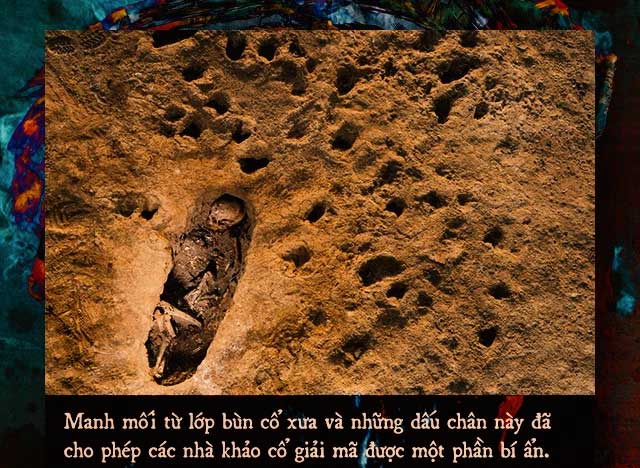

As the ancient mud was revealed, two archaeologists lay flat and began to excavate with their specialized trowels. The shape of a small tomb started to emerge. At its center was the top of a child’s skull, still adorned with a tuft of black hair.

At this point, the archaeologists switched from trowels to brushes. They carefully swept away the dust, revealing the intact remains of the skull. Soon, the neck and shoulder bones began to emerge beneath a rough cloth. Finally, the entire body of the child was uncovered, curled up beside the remains of a llama.

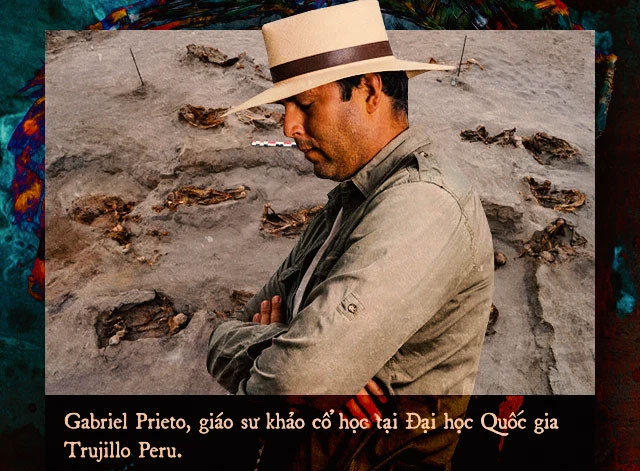

Gabriel Prieto, a professor of archaeology at the National University of Trujillo, looked into the tomb and nodded. “Ninety-five,” he said. This was the 95th child Prieto had found in this mass grave in Huanchaquito.

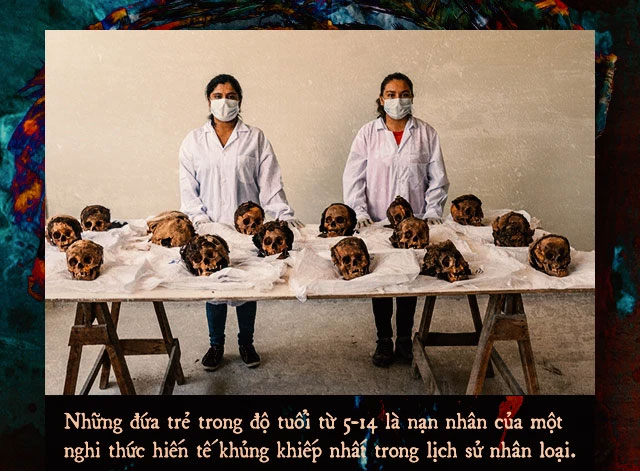

In total, combined with another nearby site, 269 children aged 5 to 14 have been discovered. The skeletons, dated to be over 500 years old, reveal a horrifying truth: All of these children were killed in an unprecedented sacrificial ritual in world history.

“This is unbelievable,” Prieto exclaimed once again, shaking his head in disbelief. This phrase seemed to have become a comforting mantra for the archaeologist and also a father, each time he uncovered another body.

Prieto struggled to find meaning in the events that unfolded here. In our time, the painful death of even one child can haunt a community. Only the most ruthless hearts remain unaffected; the specter of mass murder terrifies everyone.

So why, here, 500 years ago, could people so callously kill hundreds of children? What desperate circumstances could explain such an unimaginable act for our modern society?

The Archaeologist’s Burden

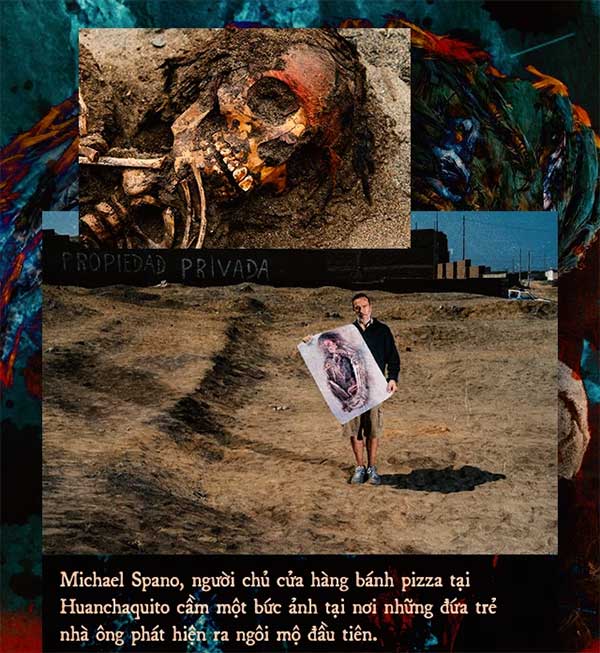

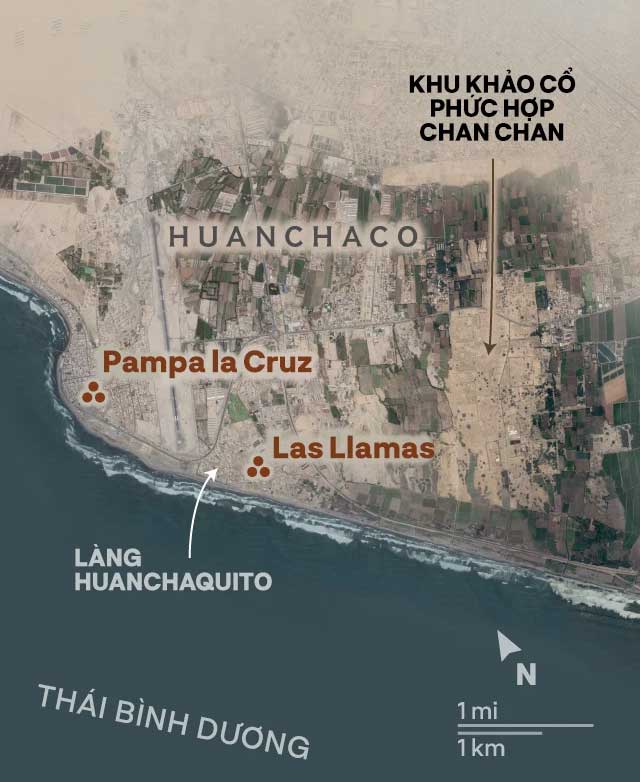

The archaeological site in Huanchaquito-Las Llamas was first discovered in 2011 by a group of local children. While playing on the beach, they and their dogs stumbled upon some bones protruding from the sand.

The frightened children ran home to tell their parents, prompting one of them, the owner of a pizza shop, to contact the police and request Prieto to investigate. He suspected that the bones were human, and thought it prudent to consult Prieto, who had grown up in the area.

Prieto was born in Huanchaco (pronounced wan-CHA-co), the town where Huanchaquito is located. From a young age, Prieto displayed a passion for exploring ancient sites. He often spent afternoons climbing the highest hill in town to hunt for beads outside a 16th-century Spanish colonial church.

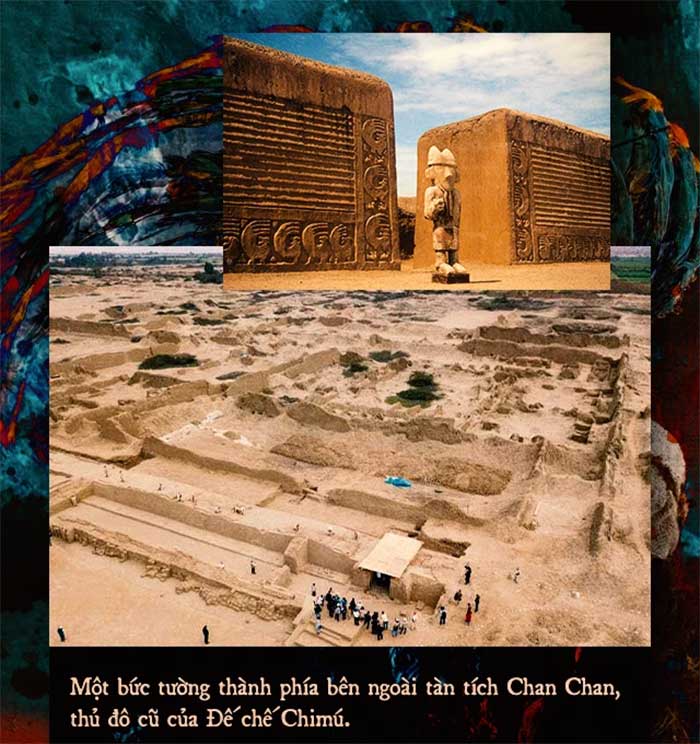

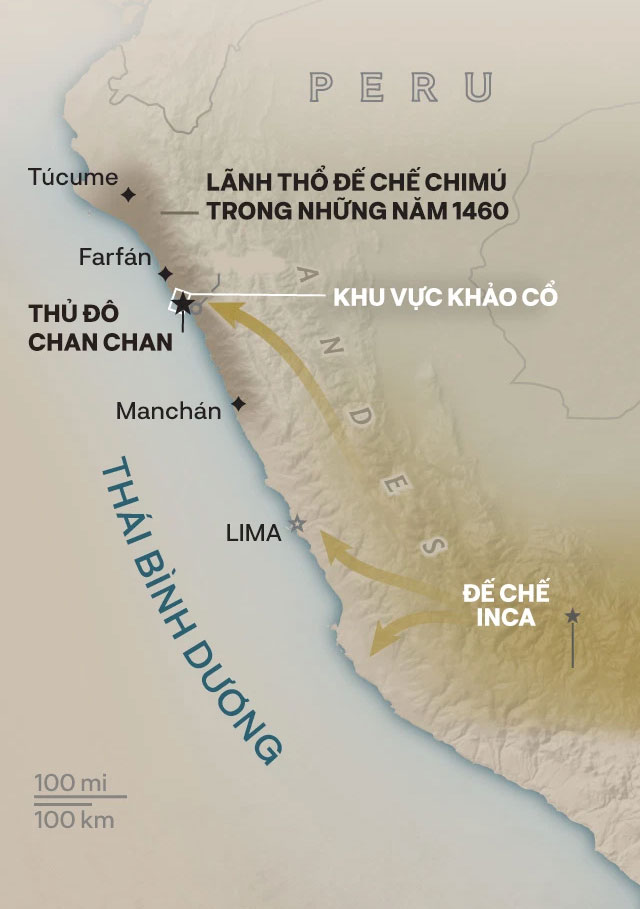

He also ventured to the southern edge of town to explore the Chan Chan ruins, the ancient capital of the Chimú people. At its height in the 15th century, Chan Chan was one of the largest cities in the Americas, serving as the power center of an empire that stretched approximately 300 miles along the coast of Peru.

All these childhood experiences inspired Prieto to become an archaeologist, and while waiting for his PhD at Yale University, he returned home to excavate a 3,500-year-old temple. That was when he was alerted by the pizza shop owner about the graves near the beach.

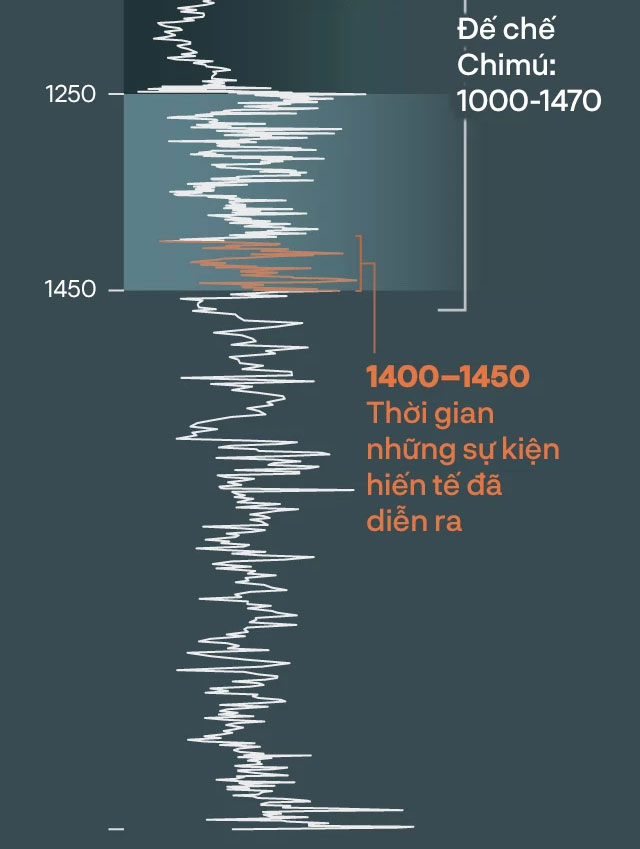

Initially, Prieto thought the remains were simply from a long-forgotten cemetery. However, after discovering the remains of several children wrapped in burial cloth — carbon dating indicated they dated from 1400 to 1450 AD — the archaeologist realized this was a much larger discovery.

Prieto observed that this burial pattern did not resemble typical Chimú funerals. The children appeared to have been bound in unusual positions — lying on their backs or sides instead of sitting upright as was customary. The burial goods also lacked the jewelry, ceramics, and other significant items typically found in Chimú graves.

Instead, many of the children were buried alongside very young llamas. As important sources of food, fiber, and transportation, these animals were among the most valuable assets to the Chimú.

Finally, and most troubling: Many of the children and animals showed clear cut marks on their sternums and ribs. There was no hesitation evident from the knife. Prieto stated that the children had been killed and their hearts removed. “It was a ritual slaughter, and it was very systematic,” he said.

A Forgotten Empire

Reconstructing the Chimú sacrificial rituals is incredibly difficult, primarily because archaeologists and historians know very little about this culture. The Chimú empire may have been the greatest empire that few have ever heard of.

This civilization existed between two much more well-known periods: the Moche empire, known for its stunning murals depicting the bloody sacrifices of war captives, and the Inca empire, which defeated the Chimú around 1470 but soon after collapsed under Spanish colonial invasion.

Strangely, historians have been unable to find any written records about the Chimú empire, despite the fact that they were a highly prosperous civilization, comparable to the Moche and Inca.

The scant clues appear in the chronicles of the Spanish, but even those are indirect accounts. They wrote that during the king’s coronation or death, the Incas would perform sacrificial rituals involving hundreds of children. However, to date, no archaeological evidence has confirmed this.

In contrast, the graves at Huanchaquito provide archaeological evidence for a similar sacrificial ritual of the Chimú, yet there are no written records. This raises seemingly unanswerable questions: Why did they sacrifice hundreds of children in an unprecedented scale ritual? And on what occasions did they do so?

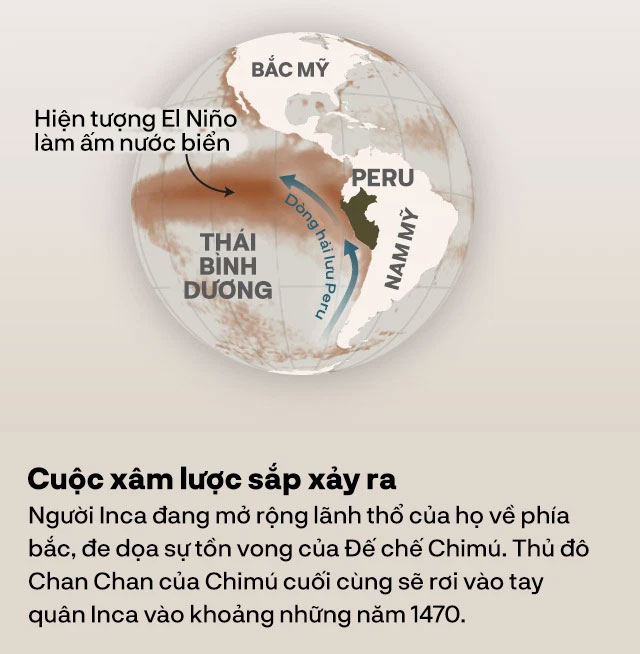

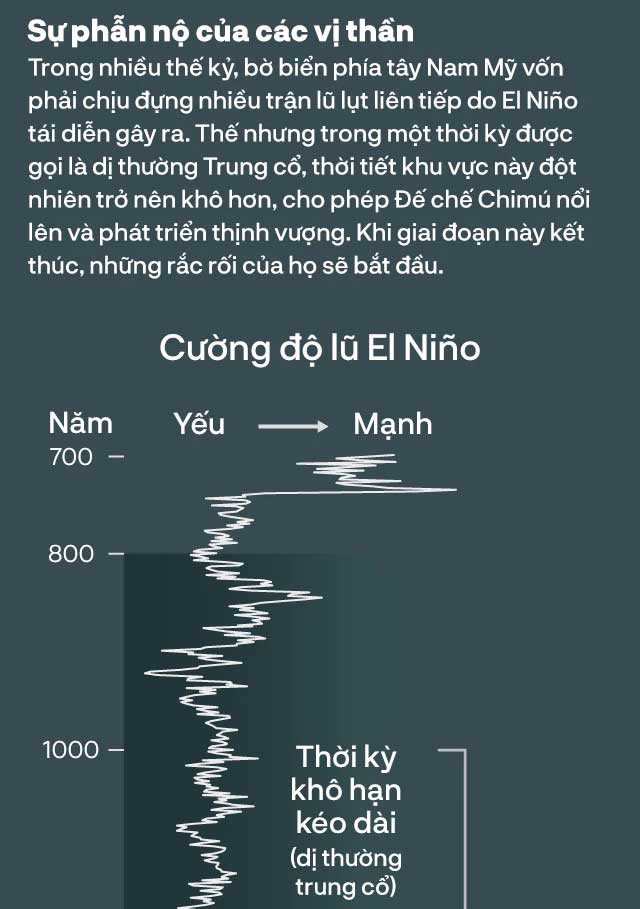

A single clue to what happened in Huanchaquito turns out to be the ancient mud layer that had dried and hardened. It indicates that the bodies of the children were buried beneath the mud. Deep mud implies heavy rainfall. In a parched coastline like northern Peru, “such rains typically only occur with El Niño,” Prieto explained.

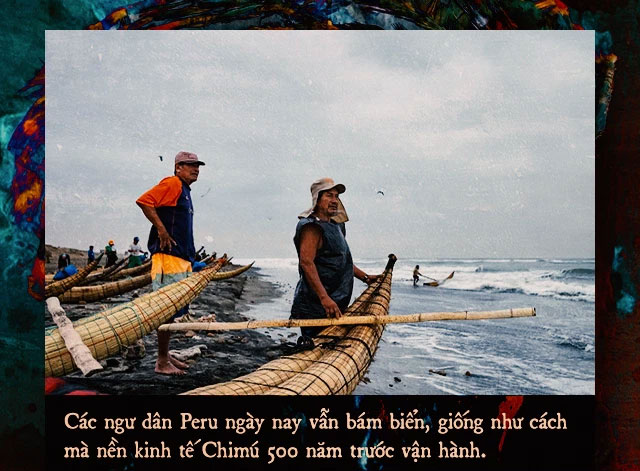

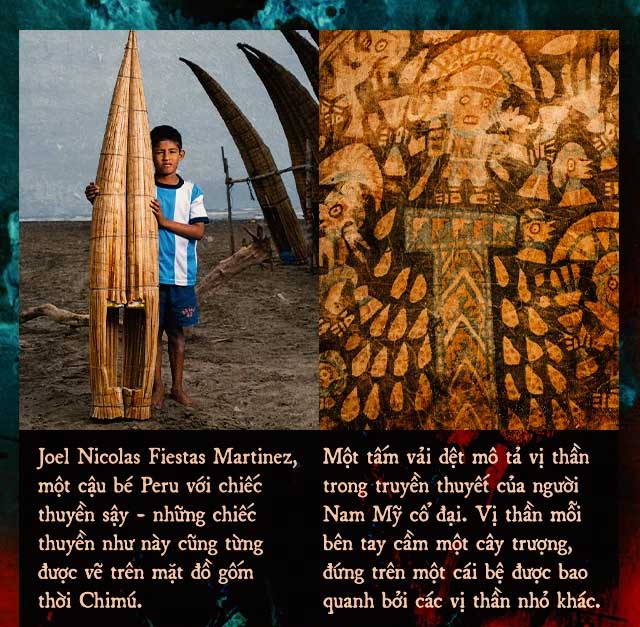

Like other South American empires, the Chimú maintained their population and prosperity in the capital Chan Chan through fishing and managed irrigation systems. Both could be disrupted when ocean waters warmed and intense rainfall occurred due to climate change.

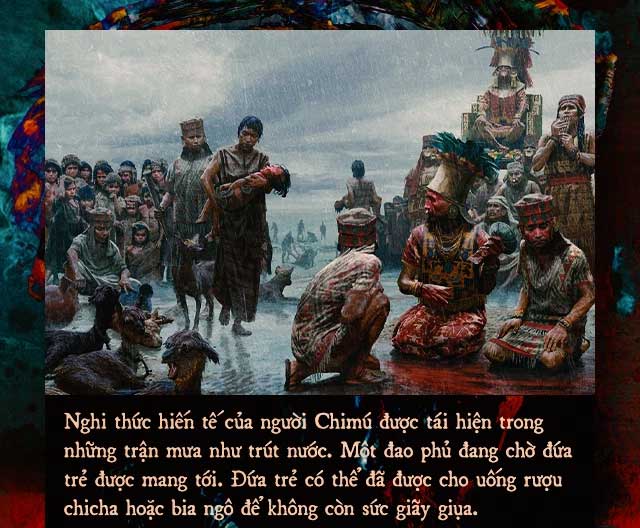

Researchers hypothesize that a severe El Niño event may have destabilized the political and economic stability of the Chimú kingdom. Consequently, priests may have ordered mass sacrifices in a desperate attempt to appease the gods.

“Based on the number of children and animals sacrificed, it must have been a significant investment on behalf of the empire to the deities,” Prieto said.

An Unprecedented Horrific Ritual in History

Jane Eva Baxter, a professor of anthropology at DePaul University who specializes in the history of children, agrees that the Chimú may have regarded their children as one of the most valuable offerings they could present to the gods.

When a family decides to sacrifice their child, and a society chooses to offer hundreds of children, they are sacrificing the future and all potential of what they possess. All the energy and effort dedicated to maintaining their family and society is now devoted to the other world.

Offering children may also represent an evolution in the rituals of pre-colonial societies in northern Peru. This evolution only occurred when they were desperate in their efforts to gain the favor of the gods.

Haagen Klaus, an anthropology professor at George Mason University, believes that children only became sacrificial victims after the collapse of the Moche civilization (the culture preceding the Chimú) in the ninth century.

Previously, the Moche had sacrificed a large number of adult warriors captured at a site known as the Temple of the Moon, just a few miles from where the Chimú ruled in the capital Chan Chan, after several centuries.

When the rituals of sacrificing prisoners and adults by the Moche failed, the Chimú empire may have thought that their offerings had lost their effectiveness. The gods seemed to have become more demanding, and they needed to continue negotiations with more valuable sacrificial items. “This is how the Chimú interacted with the universe in a way they understood,” Klaus said.

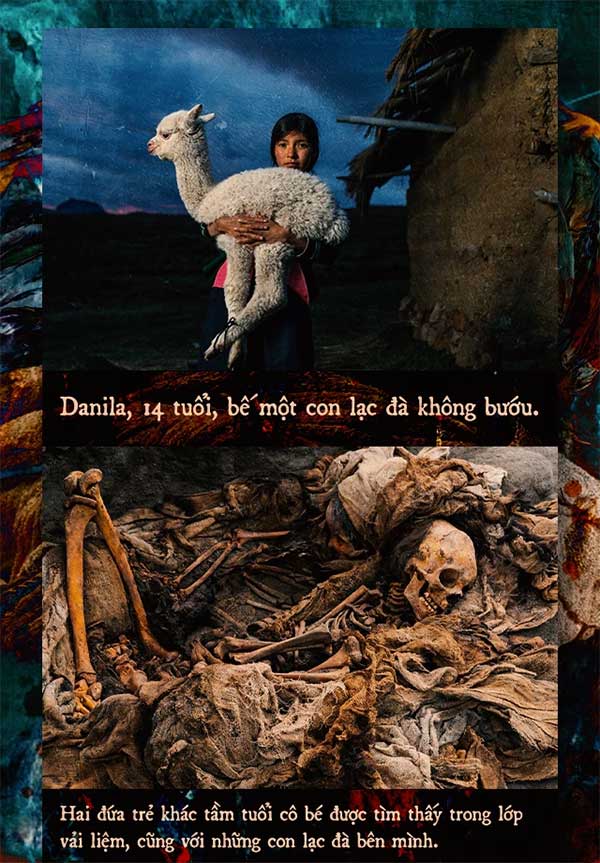

The need to appease the spirits and prevent rain may have been urgent, but the mass sacrifice itself seems to have been carefully orchestrated. Another valuable resource was the young Bactrian camels that were meticulously selected from herds owned by the empire.

Nicolas Goepfert, a camel expert at the French National Center for Scientific Research, analyzed the burial wrappings of the camels. He found that the Chimú might have chosen the animals for sacrifice based on their age and color. For instance, dark brown Bactrian camels were often raised alongside light brown camels, while no white or black animals were sacrificed.

“We know from Spanish chronicles that the Incas had a color code for sacrificial Bactrian camels. Perhaps the Chimú also selected camels in that way,” Goepfert explained.

However, how the children were selected for their terrible fate remains a mystery. Studies have found that both male and female children were killed at Huanchaquito, all well-cared for, with few signs of malnutrition or illness.

Isotope analysis of their teeth shows they came from various regions of the vast Chimú empire. The backs of some skulls were unusually elongated, evidence of a deliberate skull modification procedure typically performed in remote highland areas.

But many questions remain unanswered. Did the children come from noble families or impoverished ones? Without burial goods, this question essentially remains unresolved.

How many families lost children in the ritual? Were they willing to give up their own offspring in the face of impending disaster, or were they forced by violence to let go? Currently, archaeologists have no answers.

But signs and forensic clues are helping them piece together part of the sequence of events.

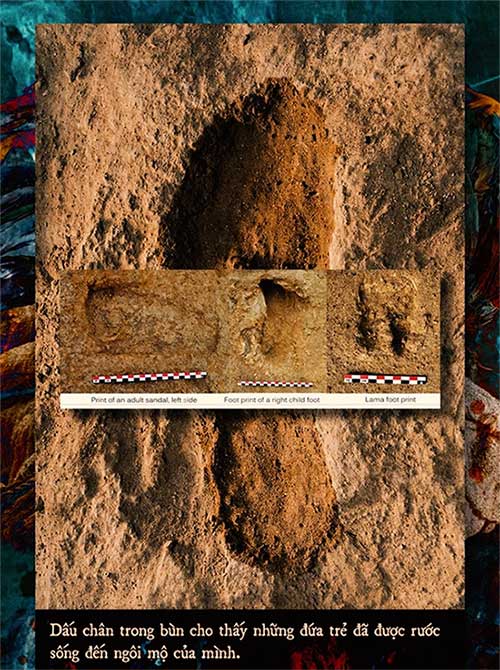

Footprints and traces preserved in the dry mud indicate that there was an official procession to the sacrificial site. The tiny bare footprints of both people and camels led Prieto to believe that the victims were led alive to their own grave, where they would all be killed.

No insects were found with the remains, indicating that the children were carefully wrapped in shrouds and quickly buried along with the camels.

Two adult women may have directly wrapped the shrouds and performed final rites for the children. They were later also killed and buried with a strong blow to the head.

Nearby, archaeologists also found the remains of an adult man, lying on his back under a pile of stones. His unusually robust body led them to wonder if he might be the executioner.

Ultimately, did this horrific ritual save the Chimú from the wrath of the gods? There is currently no evidence to answer that question. But based on the timing of its execution, perhaps the Chimú lost both children and a significant amount of wealth right before their civilization fell into ruin.

“This is when you have the most to lose and you are giving the most,” Baxter said. Just a few decades later, Inca warriors would reach the very walls of the capital Chan Chan and topple the entire Chimú civilization.

Lives Worth More Than Gold

Months after the excavation at Huanchaquito concluded, Prieto continued to find more children and Bactrian camels at another sacrificial site known as Pampa la Cruz. The new site is a vacant lot on a high hill, where a large wooden cross stands. This cross was erected by a fisherman in gratitude for surviving a miraculous drowning.

Further south along the coast, a new monument has been erected to honor the victims sacrificed at Huanchaquito. There, a statue of a boy and a Bactrian camel is surrounded by newly planted palm trees, each palm symbolizing a person.

In total, Prieto has discovered the remains of 132 Chimú children, most executed with the familiar horizontal cut across the chest, and buried in simple shrouds. The total number of victims found at both sites now amounts to 269 children, 3 adults, and 466 Bactrian camels.

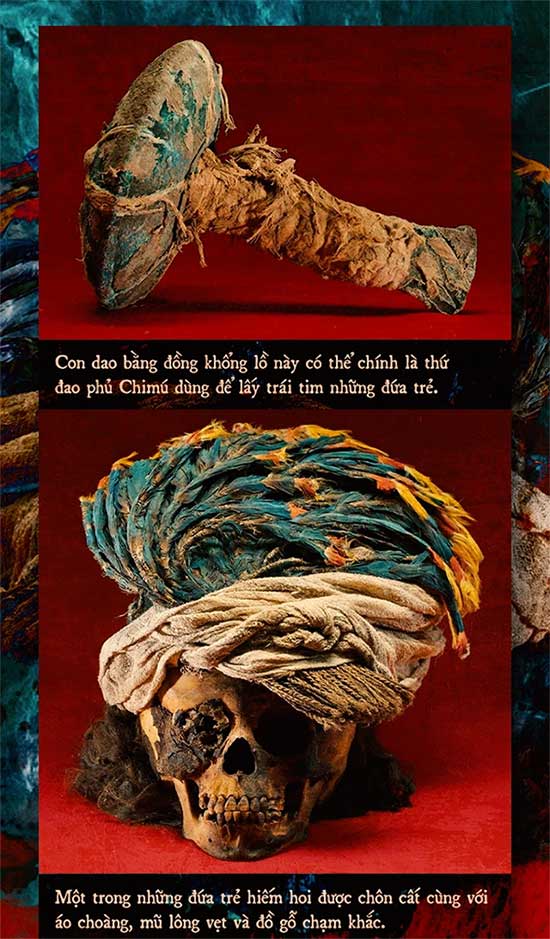

But what confounds Prieto the most is 9 graves concentrated on the hilltop right next to the ruins of a Moche temple facing the sea. These graves also contained Chimú children, but they were buried in elaborate cloaks and headdresses adorned with feathers and carved wood.

None of the 9 victims had chest cuts; only the skull of one child had been severely damaged by a fatal blow to the head.

Prieto later unearthed a massive bronze knife with a clattering sound at one end, unlike anything previously discovered by any archaeologist. “My God, what is this?” he exclaimed upon finding it. Could this knife be what was used to kill the children buried here?

As for the rest, Prieto is still struggling to understand the motives and logic behind the Chimú’s mass sacrifice. But one afternoon during a lunch break, he shared an old story that somewhat diminishes the brutality of this ancient civilization.

Spanish colonial chronicles record that after conquering the land, they captured Don Antonio Jaguar, a rare surviving leader of the Chimú empire. Jaguar escorted his new Spanish lords to a priceless treasure.

According to legends in Huanchaco, Don Antonio directed them to a site called peje chico – meaning the smaller treasure. As for peje grande – the greater treasure, it remains undiscovered to this day.

“I want to believe that the children are indeed that great treasure, that they are the most precious thing to the Chimú people</em,” Prieto reflected. “Their lives must be worth more than gold.”