Engineers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have discovered that Leonardo da Vinci’s understanding of gravity was centuries ahead of his time.

In a paper published in the journal Leonardo, the research team examined one of da Vinci’s notebooks and found that the renowned polymath devised experiments to demonstrate that gravity is a form of acceleration. He even modeled the gravitational constant with an accuracy of about 97%, Phys.org reported on February 13.

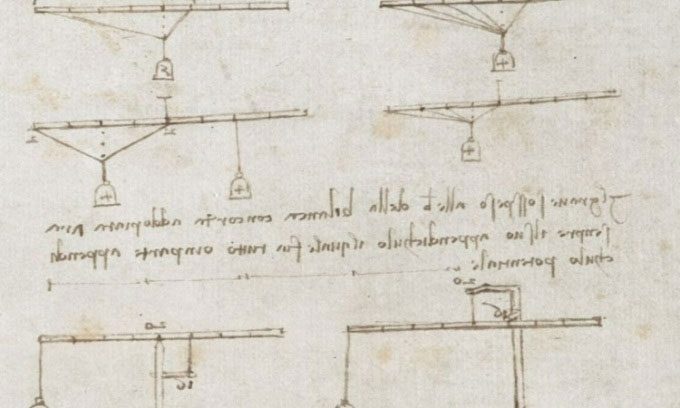

Da Vinci’s gravity experiment notes. (Photo: British Museum)

Da Vinci, who lived from 1452 to 1519, made significant strides in exploring this concept. It wasn’t until 1604 that Galileo Galilei hypothesized that the distance traveled by a freely falling object is proportional to the square of the time. It was not until the late 17th century that Isaac Newton developed the law of universal gravitation, describing how objects attract each other. The main obstacle for da Vinci lay in the limitations of the instruments available to him. For instance, he lacked the equipment to accurately measure the time it took for objects to fall.

Da Vinci’s experiments were first uncovered by Mory Gharib, a professor of aerospace engineering and medical engineering, in the Codex Arundel, a collection of da Vinci’s notes on science, art, and personal subjects. In early 2017, while studying da Vinci’s technique for displaying flow to discuss with graduate students, Gharib noticed a series of sketches depicting triangles formed by grains of sand pouring from a jar.

To analyze the notes, Gharib collaborated with colleagues Chris Roh, an associate professor at Cornell University, and Flavio Noca from the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland in Geneva. Noca provided a translation of da Vinci’s notes from Italian. In the notes, da Vinci described an experiment where a water container moves in a straight line parallel to the ground, pouring water or granular material (likely sand) during the process. He observed that the water or sand would not fall at a constant velocity. Instead, they would accelerate. Unaffected by the container, the material would cease to accelerate horizontally, and its acceleration would only be directed downward due to gravity.

If the container moves at a constant speed, the line created by the falling material will be vertical and will not form any triangles. If the container accelerates uniformly, the line formed by the collection of falling material will be diagonal, creating a triangle. Da Vinci pointed out that if the container accelerates at the same rate as the material falling due to gravity, it would create an equilateral triangle.

Da Vinci sought to describe that acceleration but was unsuccessful. By using computer modeling to conduct da Vinci’s water container experiment, the research team identified the error he made. “We found that da Vinci modeled the distance of the falling object as proportional to the second power of time instead of the square of time,” Roh stated.