The optical illusion that makes the Moon appear gigantic when near the horizon is the most famous illusion in the world, and no expert has been able to provide a definitive explanation.

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that Earth’s atmosphere magnifies the Moon when it is close to the horizon. This hypothesis has been proven incorrect. The scattering effects of the atmosphere can make the Moon appear red or orange but do not change the size of the celestial body, according to Vox.

The Moon at the horizon appears much larger. (Photo: NASA).

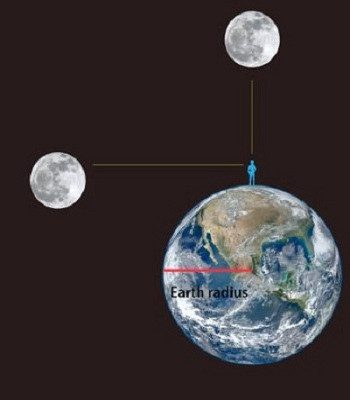

Using a tool called a theodolite, astronomers can determine that a full moon has a width of 0.52 degrees (compared to the 360 degrees of the entire sky) and remains constant throughout the night. In fact, according to precise measurements, the Moon at its zenith is about 2% larger than the Moon at the horizon, due to the greater observational distance to the horizon.

The phenomenon of the Moon appearing larger is entirely due to the human brain. “Humans are seeking a simple answer,” says Donald Simanek, a physicist who specializes in lunar illusions. “But this answer lies within the functions of the human brain, of which we know very little.”

Measurements show that the Moon at the zenith is larger than the Moon at the horizon. (Photo: Bob King).

Recently, some neuroscientists have begun using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate the cause. Although they have not yet reached a final conclusion, their research helps explain part of how the brain interprets visual information.

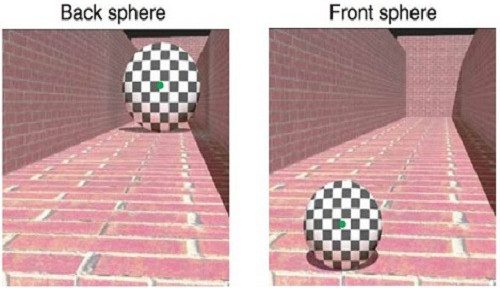

A 2006 MRI study simulated a similar illusion in a laboratory setting. A sphere on the left appears larger and further away than a sphere on the right, even though the actual sizes of both are the same. This phenomenon is similar to the illusion of the Moon appearing larger at the horizon.

The researchers proposed a hypothesis to explain this error of the brain. As a car moves farther away, its angular size decreases. Knowing that the car is not shrinking, the brain adjusts the perceived size so that we still see the car as the same size as it moves away.

The sphere on the left appears larger and further away than the sphere on the right, similar to the Moon at the horizon. (Photo: Murray).

At a much greater distance, such as with the Moon, we cannot perceive the depth accurately. If the horizon appears much further away than the zenith position, this mechanism will also deceive the brain, making the Moon seem larger than its actual size.

“If the estimated distance to the Moon is larger, the brain will perform calculations and conclude that objects must also be larger to fill the same space,” said Ralph Weidner, a German neuroscientist studying the lunar illusion using MRI experiments.

Almost everyone surveyed reported that the Moon looks both large and near, rather than distant. Researchers have updated explanations based on neuroscience studies to address this issue. According to this, our brains have two basic systems for processing visual information: one determines what you will see (ventral stream) and one identifies the position of the observed object (dorsal stream). Each system corresponds to a different area of the brain.

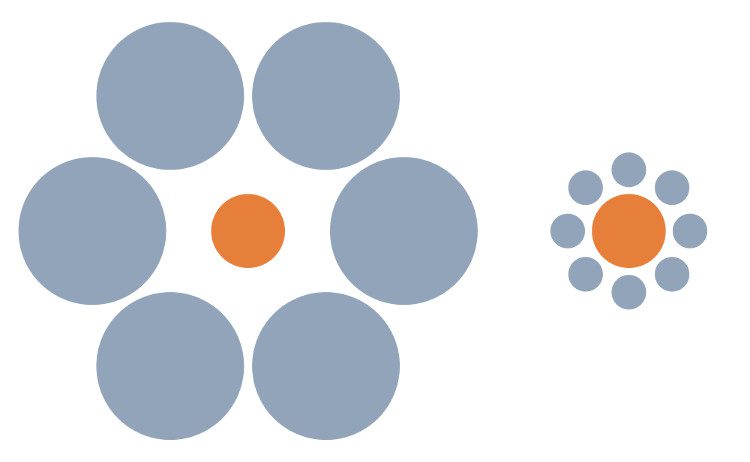

Ebbinghaus illusion, the circle on the left appears smaller than the one on the right. (Photo: Phrood~commonswiki).

The new hypothesis suggests that these two systems work sequentially to create the lunar illusion. The ventral stream processes information in the traditional way, self-adjusting for the Moon to appear larger when seen at a distance. The dorsal stream then reassesses the Moon’s position, reasoning that it appears larger than normal, indicating it must be close, Weidner states.

Weidner and colleagues tested this hypothesis by placing individuals in an MRI machine and using 3D glasses for them to see the lunar illusion, along with another illusion that operates similarly.

Participants in the experiment saw a circle moving closer or farther away, but the angle of view was always adjusted to maintain a constant value. All volunteers reported that they perceived the circle as larger when it moved away, similar to the Moon.

The researchers concluded that the ventral stream of the brain is active for both types of illusions. While not providing conclusive evidence, the experiment showed that the size-distance effect is indeed related to the lunar illusion of the larger Moon at the horizon.

When the Moon is placed next to familiar objects on the horizon, we can assess its vast size. When the Moon is high in the sky, there are no familiar objects to provide a comparative context, making it look less monumental and smaller.

However, as NASA explains, these are not perfect explanations. They note that astronauts in space also experience the lunar illusion, but they do not face the same issues with foreground objects on the horizon skewing their sense of distance and size.

Ultimately, NASA remains stumped and offers the following conclusion: “In the absence of a complete explanation for why we see the lunar illusion, we can still agree that – real or illusion – a gigantic Moon is a beautiful sight.

So, until someone decodes exactly what our brains are doing, perhaps it’s best to simply enjoy the lunar illusion and the gloomy, claustrophobic, and sometimes utterly haunting vistas it creates.”