Our prehistoric ancestors from the Paleolithic era practiced cannibalism. Homo sapiens did it. The Neanderthals did it. Homo erectus and Homo antecessor did it. It is highly likely that most hominins engaged in cannibalism in some form. The only questions are “why” and “how much”?

Evidence of the “Cannibalism Era”

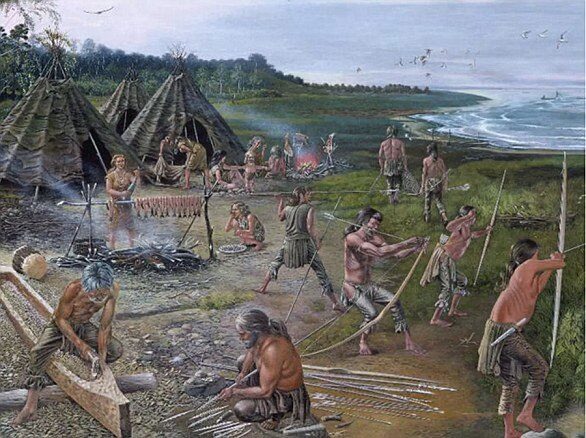

From our privileged position today as the dominant species in the food chain on Earth, with a relatively abundant supply of plant and animal food compared to earlier times, cannibalism elicits disgust among most people. But did this aversion exist among our ancestors? Scientists often regard cannibalistic practices in the Paleolithic era as exceptions rather than the norm, but that may just be a fantasy. It is perhaps more fitting to envision our ancient relatives as benevolent hunter-gatherers rather than as brutal opportunistic cannibals.

Did prehistoric people resort to cannibalism out of hunger?

As Dr. James Cole, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of Brighton, noted in a 2017 study, “Given the sparse nature of the hominin fossil record, the fact that we have direct evidence of cannibalism suggests that this behavior may have been more common in prehistoric populations than the number of archaeological sites indicates.”

Cole described several clear signs on fossilized human bones that suggest cannibalistic practices: “absence of cranial bases (to access the brain) on complete or nearly complete skeletons”; “almost no vertebrae (due to crushing or boiling for marrow and fat)”; “cut and chop marks”; “comparable techniques for butchering human corpses as well as animal remains (food)”; “treatment of hominin remains similar to that of animal remains”; “evidence of cooking in the form of burned bones”; “human bite marks.”

These indicators have been discovered at ancient human sites around the world, dating from 10,000 to nearly 1 million years ago. At the Goyet Cave in Belgium, researchers found evidence that about 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals butchered and then consumed some corpses of their own kind, using their bones as tools. In Gough Cave in the UK, anthropologists uncovered bite marks on 15,000-year-old Homo sapiens bones, as if ancient cannibals were trying to scrape every millimeter of nutritious muscle. They also discovered hundreds of filleting marks and ritualistic cuts on the bones, and even skulls that appeared to have been modified for use as… cups.

Why Cannibalism?

So, did humans consume others to avoid “wasting food” after the death of a group member? Was it truly necessary in times of scarcity? Or were humans in rival groups hunting each other like they would deer or wild boar? Cole attempted to answer this question by calculating the caloric yield from “feasting” on an adult male. He found it to be approximately 143,771 calories, enough to sustain a group of about 25 adults for half a day.

He argued that this nutritional yield would not be significant, especially compared to hunting horses, aurochs, or mammoths, thus dismissing the notion that ancient humans frequently hunted one another. Cole wrote: “Just one large animal provides more calories without the difficulties associated with hunting intelligent and agile groups of hominins.”

This suggests that cannibalism in the Paleolithic era was likely opportunistic, driven by necessity or perhaps for ritualistic purposes, Cole added. This practice certainly existed in ancient civilizations, but we may forever leave it shrouded in darkness.

The Korowai Tribe is one of the last tribes in the world known to have practiced cannibalism.

The Korowai, or Koroway, Kolufo are an indigenous people residing in the forests of the far east of Papua province in Indonesia. The Korowai were discovered in the 1970s. They live in a tribal social organization and are one of the most primitive tribes in the world, known for their unique tree-dwelling lifestyle, isolated from the outside world for centuries. According to the Indonesian census, this tribe has nearly 3,000 members scattered throughout the forests of Papua.

The Korowai once practiced headhunting and cannibalism, and they are considered a ferocious and reclusive cannibal tribe. Members of the Korowai tribe specialize in living in treetops, maintaining primitive customs. A group of these people hunts in a remote forest in Indonesia, officially recognized as the first tree-dwelling tribe, speaking their own language and surviving on the flora and fauna of the forest.

Ethnologists report that the Korowai were discovered in the 1970s, at which time they still practiced customs like headhunting and cannibalism. They would eat human brains immediately after killing. It remains unconfirmed whether the tribe has completely abandoned cannibalism. However, some opinions suggest that, unlike the horrific tales propagated, the Korowai only engaged in this practice as punishment for wrongdoing. Traditionally, the family of the victim was entitled to kill and eat those who committed evil against the tribe. Today, they no longer adhere to this terrifying custom, but the skeletal remains—dark remnants of Papua New Guinea’s past—are still preserved by descendants of the tribe, and anthropologists believe that contact with the outside world has ended this practice in recent years.

In reality, the main diet of the Korowai consists of various wild game; they primarily eat wild boar, deer, sago palms, bananas, and various insects and plants. Sago is the primary food in their meals, and the sago palm is harvested 4-6 weeks before it is processed into food. After harvesting, it is left to rot in the swamp where larvae can develop. After 4-6 weeks, the palm will be split open to retrieve the larvae of the Capricorn beetle, which is a favorite delicacy among the Korowai. They can eat them raw or cooked. The larvae have a rich, fatty flavor and an enticing aroma. They provide a significant source of fat for the tree-dwelling Korowai. Korowai women collect the larvae from the sago tree and then grind a sago palm branch into a fine powder, which is a staple in their meals.