Before the emergence of Silicon Valley, scholars in ancient Iraq created a knowledge center that encouraged innovation.

Throughout history, collaboration has been regarded as the primary driver of innovation in science and technology. Consequently, some of the most significant scientific advancements have originated from knowledge centers. Today, when we think of a hub that concentrates numerous organizations and encourages collaboration, Silicon Valley often comes to mind. However, this was not the first place to realize this idea; many centers paved the way for it, among which Baghdad, Iraq, during the Islamic Golden Age in the 4th century AH (10th century CE) is notable.

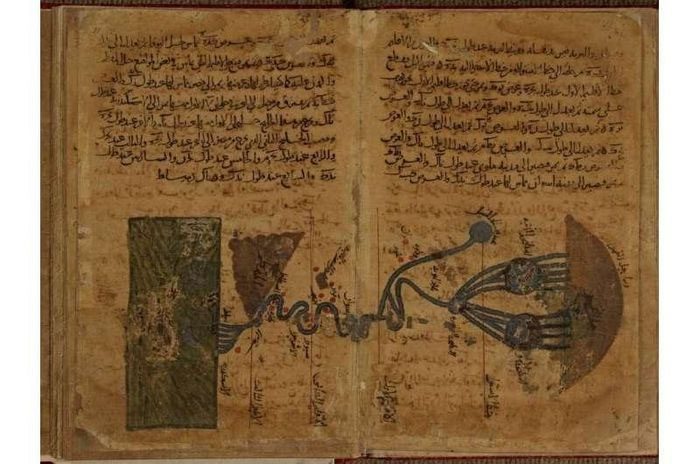

Illustrations by Al-Khwarizmi in the book Kitab Surat-al-ard (11th century) are considered the earliest maps of the Nile River. (Photo: Wiki Commons).

During this period, while Europe was experiencing the “Dark Ages,” The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) was established. Here, many great works from Persia, China, India, and Greece were collected and translated into Arabic, including the works of Aristotle and Euclid.

The cultural and linguistic diversity fostered lasting legacies of innovation in fields such as algebra, geography, astronomy, medicine, and engineering.

Automated Machinery

Existing for about three and a half centuries, The House of Wisdom was home to some of the greatest thinkers. Among them were the Banu Musa brothers – three Persian scholars living in Baghdad during the 9th century, each with their own specialization: one was a mathematician, another an astronomer, and the third an engineer.

They translated works from various languages into Arabic, assisted other translators, and invested money in acquiring rare manuscripts. They were also involved in urban infrastructure development and even had talents in music.

However, their most notable contribution was automata, or automated machines. In a work published in 850 CE, The Book of Ingenious Devices, also known as The Book of Tricks, they described machines considered precursors to modern robots.

These automata included mechanical musical instruments and a steam-powered robot that could play the flute. Teun Koetsier from Vrije University Amsterdam regards this mechanical “musician” as the first programmed machine in the world.

Genius Scholars

Another scholar who lived in The House of Wisdom at that time was Mohammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, whose name inspired a term we commonly use today: “algorithm.”

In fact, the term “algebra” also derives from the title of one of his books – Kitab fi al-Jabr wa al-Muqabala – a manual on computation using completion and balancing.

This is one of the (if not the) earliest publications in the world that addresses algebraic rules. He also made significant contributions to geography and astronomy. Al-Khwarizmi collaborated with al-Kindi, who is also known by his Latin name Alkindus.

Al-Kindi was an Abbasid scholar. He was a citizen of the Abbasid Empire, which spanned the Arabic-speaking regions from present-day Pakistan to Tunisia, and from the Black Sea to the Indian Ocean. He was a mathematician, a student of cryptanalysis, and a pioneer in music theory, who integrated Aristotle’s philosophy with Islamic theology.

Al-Kindi is credited with introducing Indian numerals to his colleagues in the Arabic-speaking community. Together with al-Khwarizmi, he developed the Arabic numerals that we all use today (i.e., the numbers 0-9).

He also authored the oldest known book on cryptanalysis and the use of statistical reasoning (a type of data analysis). Statistician Lyle Broemeling describes this as one of the earliest examples of both methods.

Al-Kindi’s personal library was so vast that it seemed to inspire jealousy in the Banu Musa brothers, prompting them to conspire against him, expel him from The House of Wisdom, and seize his library, making it their own.

Vanishing Without a Trace

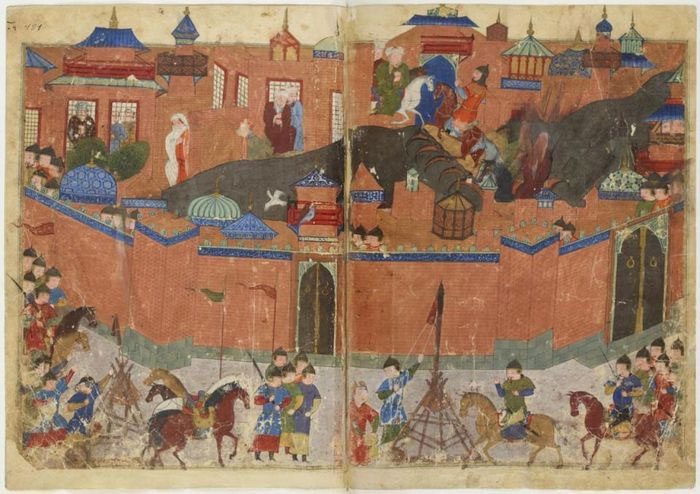

After centuries of “nurturing” wisdom and advancing science and technology, The House of Wisdom was destroyed by the Mongols during the Siege of Baghdad in 1258 – leaving no trace behind.

A painting by Persian historian Rashid al-Din Hamadani depicts the siege of Baghdad in 1258 by the Mongols. The Mongol army was led by Hulagu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan. (Photo: National Library of France).

The absence of any recorded archaeological evidence has led some scholars to doubt its existence. Some believe that The House of Wisdom did not exist as a physical location but rather as a state of mind.

In his book Greek Thought, Arabic Culture, Dimitri Gutas suggests that The House of Wisdom was likely romanticized into an “ideal national repository.” However, Islamic studies expert Hossain Kamaly argues that this view is unconvincing.

Nonetheless, Gutas himself acknowledged that from 800 to 1000 CE, there was a large-scale translation movement in the Middle East, which resulted in many complete and systematic translations of non-literary Greek works into Arabic. Translators were highly regarded. Their social prestige, along with that of the elite, helped increase funding for translation activities.

Renowned science communicator and theoretical physicist Jim al-Khalili summarized in his book The Pathfinders:

[I]t was indeed The House of Wisdom […] that significantly expanded its scope from a mere palace library […] to become a center of original scientific scholarship.

In other words, The House of Wisdom may have been a small space, but it was a crossroads of interdisciplinary knowledge in a diverse and dynamic environment. It left a valuable legacy for modern science.

Scholars often received financial support from various caliphs – the political and religious leaders of Islamic nations. In other words, scholars focused on receiving “scholarships” rather than seeking grants. Moreover, all methods of learning to acquire knowledge were equally respected, rewarded, and encouraged, leading to social stability and prosperity.

Although there is still much we do not know about The House of Wisdom, we recognize that rich ideas have historically emerged in a dynamic, interdisciplinary environment. This leads us to wonder: does the clear division of disciplines, as we often do – assuming that science and technology and social sciences are two opposing fields unrelated to each other – hinder innovation?