Further references and explanations regarding the development process of the Lucky Iron Fish and its benefits.

The Lucky Iron Fish Helps Prevent Anemia

Following the publication of the article “The Lucky Iron Fish helps prevent anemia for people in poor countries with difficult living conditions“, there have been questions about its validity. Can the Lucky Iron Fish actually supplement iron for people? Is it safe to use? This article aims to provide additional references and clarify the development process of this fish as well as the benefits it offers.

“You can have the best treatments in the world, but if people don’t use them, they are useless.”

Canadian Doctor Christopher Charles and the Lucky Iron Fish he developed

Recognizing that a simple iron plate was not appealing to the locals, Charles and his research team decided to shape the iron into a lotus flower. However, the villagers continued to reject this shape. After consulting with the village elders, Charles discovered that the image of a fish was considered a symbol of luck, health, and happiness by the local residents. Thus, they used iron to create the shape of a fish and succeeded in gaining acceptance.

The villagers became more fond of this product, and after a period of use, the Lucky Iron Fish quickly led to an increase in iron levels in the blood, with cases of anemia being completely eliminated.

Clinical trials continued from September 2008 to February 2009, and results showed that the iron levels in the blood of those using the Lucky Iron Fish increased for at least three months.

However, continued usage did not significantly elevate blood iron levels. The study was conducted from the end of the rainy season to the beginning of the dry season, during which the villagers stored rainwater for use during the dry season. In the study area, the team found that the water pipes led to high concentrations of arsenic and manganese, affecting the presence of iron, thereby isolating it from being absorbed by the body through food. Noticing the difference in water quality as a confounding factor, they conducted a second study to address this issue.

Ultimately, the research team concluded that compared to pre-trial blood iron levels, individuals using the Lucky Iron Fish had increased blood iron levels after 12 months of use, with anemia rates decreasing by 43%.

Production costs are $5 per fish. Sold for $25, with 3 fish donated for free to the people of Cambodia for each purchase.

In December 2012, biomedical scientist Gavin Armstrong at the University of Guelph officially established the Lucky Iron Fish Project to commercialize the iron fish. The company utilized scrap iron from a local factory, recycling it to produce the Lucky Fish.

The company then intensified product promotion in rural villages starting in October 2013 and launched a marketing campaign in Kandai province, Cambodia, in January 2014.

By 2011, the production cost of each fish was about $1.20. By May 2014, the company announced it had raised over $690,000 and would produce the Lucky Fish in bulk at a cost of $4 each. After receiving $1.1 million from private investors, the company supplied 11,000 fish to non-governmental organizations in the first five months of 2014.

They sell the fish to everyone, who can buy them for personal use or as gifts. Additionally, they plan to sell the Lucky Fish in Canada for $25 each.

On April 28, 2014, the company announced in a press release that it had achieved B Corporation certification and established a non-profit organization headquarters in the United States.

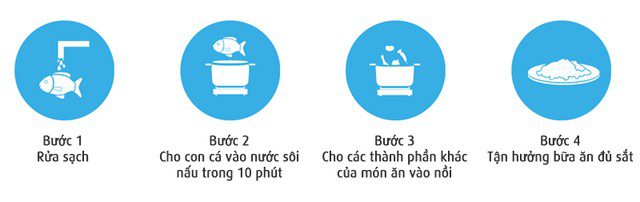

How to Use: Boil for 10 minutes with food, adding lemon to increase iron absorption in the intestine.

Each Lucky Iron Fish is 7.6 cm long and weighs 200 grams. It is placed in the cooking pot with a bit of lemon added and boiled for 10 minutes with 1 liter of water. Lemon juice will enhance iron absorption in the intestine. The fish can also be cooked with rice or stews if desired.

The percentage of people using the fish regularly reached 92%, and many of them even recommended it to friends and family as a symbol of good luck. The iron blocks are designed to maximize iron diffusion during cooking, thereby maximizing the amount of iron transferred from the fish to the food or water consumed by the people.

This is considered its unique feature: when exposed to high temperatures for the right amount of time, it releases an amount of iron equivalent to the recommended daily dietary intake.

Results show that on average, those using the fish ensure 75% of the recommended daily iron intake. They report that the iron does not alter the taste of food or water.

The project hopes to engage young people in Cambodia to expand outreach, as the older population often has high illiteracy rates, especially in remote rural areas.

Question: Can other iron objects be used in place of the Lucky Iron Fish?

Browsing through the comments, I see many people questioning whether the $25 Lucky Iron Fish (approximately 500,000 VND) is still too expensive for many people’s income. Interestingly, some suggest why not just use a regular iron block, pieces of iron, or even nails in their cooking pot.

Firstly, according to the research above, if households use cast iron or iron cookware for cooking, combined with consuming iron-rich foods, they can reduce iron deficiency rates, thus keeping their anemia rates low. Many impoverished individuals in Cambodia and elsewhere cannot access such alternatives and hence rely on the Lucky Iron Fish. That is the case with cast iron cookware.

However, using ordinary iron bought from stores, even nails, cannot guarantee health. Why? Besides iron, these industrial products may contain additional heavy metals such as lead, nickel, cobalt, and arsenic, all of which are toxic to the human body.

Moreover, the design of the fish has been optimized so that when exposed to heat, the amount of iron released into food is precisely what is recommended in nutritional guidelines, meaning that substituting with a different shape without prior calculations will likely result in reduced effectiveness.

A Brief History

Statistics show that approximately 60% of pregnant women in Cambodia suffer from anemia primarily due to iron deficiency in their diets, leading to premature birth and other complications. This increases the incidence of developmental issues in children. Iron deficiency is classified as the “most common nutritional disorder” in Cambodia, affecting 44% of the population and causing an annual loss of $70 billion in GDP.

In May 2015, Christopher Charles graduated with a degree in biomedical science from the University of Guelph, Canada. At that time, Charles received funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) to conduct epidemiological research in Cambodia. He chose Cambodia for its need for volunteers and researchers to develop a diet rich in iron. Upon arriving in Cambodia, Charles worked at the Preak Russei research center and began collecting blood samples from villagers in Kandai province.

In the past, it has been known that cast iron cookware is one of the ways to supplement iron in food during cooking. However, for many people in rural Cambodia who earn less than $1 a day, this is truly a luxury item. Even foods that are good sources of iron, such as red meat, iron-rich beans, or iron supplements, are often out of reach.

As a solution, the research team provided iron plates to the local community and asked them to place the plate in the pot while cooking soup or boiling drinking water. However, many women in the area showed hesitation towards the request to use the iron plate while cooking. In fact, many even refused to use it. Charles shared that this posed a challenge in social marketing.

A few weeks before completing his research and returning to Canada to finish his master’s program, Charles called his advisor, Dr. Alastair Summerlee, to ask for an extension. Dr. Summerlee advised Charles to focus on the anemia research project, and unexpectedly, this topic would also become the subject of Charles’s doctoral defense.