Thousands of years ago, the Egyptians artificially incubated eggs by constructing two-tiered incubators made of brick and lighting fires above them.

Today, chicks on farms are almost never hatched by their mothers. Instead, they are incubated using artificial heat in large electric incubators known as incubators, devices that can hold hundreds, even thousands, of eggs at once. Electric incubators are a modern invention, but the practice of artificial incubation has existed for thousands of years.

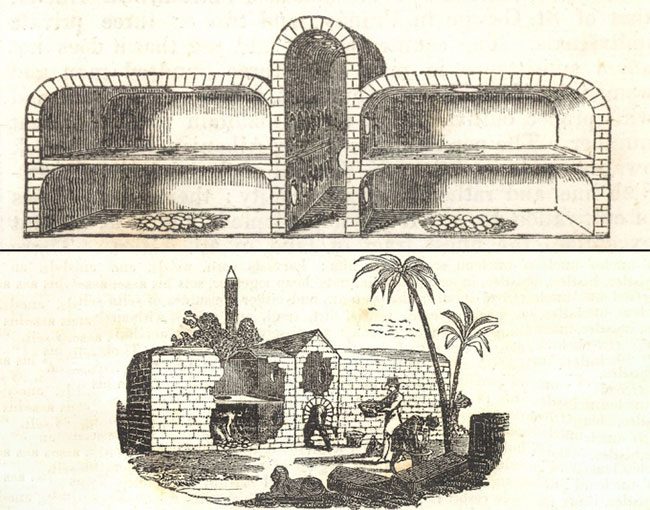

Illustration of an ancient Egyptian incubator. (Photo: Amusing Planet).

The ancient Egyptians were the first to use poultry incubators. They made a strong impression on foreign visitors who had never seen anything like it.

Many travelers left behind perplexing notes about the strange methods Egyptians used to hatch chicks. As the workings of the incubators were rarely explained in detail, they often had to guess and frequently made mistakes.

One writer suggested that the Egyptians sat on and incubated the eggs. The priest Simon Fitzsimons, who visited Egypt in the 14th century, wrote that chicks hatched from eggs due to fire, without the need for roosters or hens. He was unaware that the eggs had been fertilized traditionally before being placed in the incubator. Even the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote about incubators, suggesting that eggs were buried in piles of dung around the 4th century BC.

The first widely read travelogue that provided a relatively accurate description of Egyptian incubators was The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, published in 1356. “There is a common building in the city filled with small incubators, and the women of the city bring chicken, goose, and duck eggs to put in the incubators. The caretakers of the building cover the eggs with the heat of horse manure, without any hens, geese, ducks, or other poultry. After three weeks or a month, the women return to collect the chicks and raise them, so that the region is filled with poultry,” Mandeville wrote.

Naturalist and scientist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur provided the first accurate description of incubators in 1750. Réaumur traveled to Egypt and visited many incubators, observing the farmers at work.

A typical Egyptian incubator is a brick structure about 3 meters high, consisting of a long central corridor with rooms on either side, arranged in two tiers. The two large tiers are equal in size, with entrances large enough for a person to crawl inside. The eggs are placed on the ground floor, resting on bedding made of flax or straw. The upper rooms are used for burning fuel, utilizing a mixture of cow dung and camel dung with straw. This allows the fire to burn more slowly and in a more controllable manner.

The caretakers typically light the fire twice a day, depending on the weather, and rotate the eggs to ensure they are warmed evenly from all sides. This process continues for about two weeks, after which they extinguish the fire. At this point, the organs within the embryos have developed, and the embryos produce enough heat to continue the incubation process for another week to complete it. Ultimately, the eggs hatch on the 21st day.

Upon returning to France, Réaumur attempted to build an incubator using Egyptian methods, but due to the cooler European climate, he was not as successful as the Egyptian farmers. After Réaumur’s death, the incubator was further developed by Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, and later by Abbé Copineau, who improved Réaumur’s design by using alcohol lamps to heat the eggs. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that the first commercial incubators appeared.

A traditional Egyptian incubator using an oil lamp to heat the eggs. (Photo: Lenny Hogerwerf/Atlas Obscura).

In the 21st century, in Egypt, hundreds of incubators still use traditional methods developed thousands of years ago, although dung has been replaced by oil lamps and electric heaters. Farmers still do not use modern equipment such as thermometers or thermostats to regulate the temperature in the incubators.

Skilled incubator workers can assess the temperature by holding the eggs to their eyelids and letting their eyes feel the heat. If it is too hot, the eggs will be sprayed with water. To check the development of the eggs, the worker simply holds the egg up to a light source like a lamp. The eggshell is thin enough for them to see inside. These skills are passed down by some families from generation to generation and kept secret from outsiders.

However, traditional incubators in Egypt may soon disappear. According to a survey conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2009, all incubator owners surveyed expressed a desire to upgrade to modern incubation methods due to higher hatch rates.