During the period when Chinese society prohibited women from receiving an education, women creatively developed and utilized a unique language to communicate and secretly express their emotions.

Women’s Script refers to a writing system known to only a few women in central China in the past.

Characters of Women’s Script on the window of a bookstore in Chengdu, southwestern China. (Photo: SCMP)

The origin of this language is unclear, but most scholars believe that Women’s Script was created in a small village in Jiangying County (Hunan Province, central China) centuries ago, during a time when Chinese society banned women from education. Women developed their own writing system to communicate with each other.

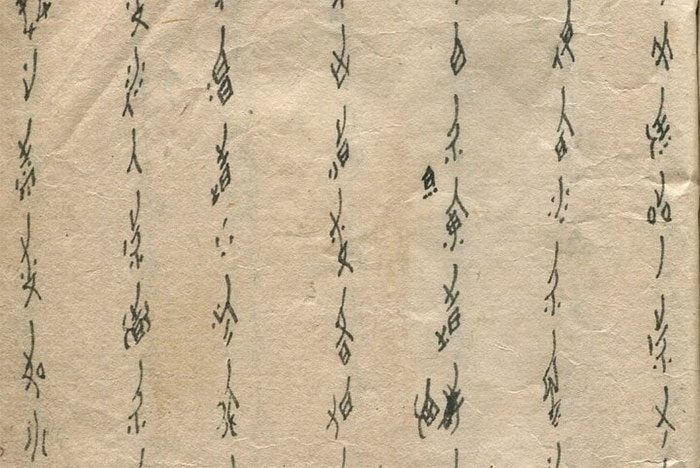

This script is soft, featuring gently curved characters that are much more compact than the modern square Chinese characters with sharp corners.

“Society didn’t allow us to go to school. So what could we do? We found ways to educate ourselves,” Xu Yan, a 55-year-old author of a textbook on Women’s Script, shared.

A sample text written in Women’s Script. (Photo: Baidu)

Women in feudal times lived under the control and arrangements of their parents or husbands. Women’s Script was sometimes likened to “teardrops,” serving as a secret tool for women to record their sorrows: unhappy marriages, domestic violence, and the longing for sisters or daughters who had married and could not return in a patriarchal society.

Xu is also the founder of the Third Day Letter, an office specializing in Women’s Script in Beijing, named after a centuries-old custom in Jiangying. The Third Day Letter is an embroidered letter gifted to a woman when she is allowed to visit her family on the third day after her marriage.

This secret world continues to resonate today as a source of empowerment for young women dissatisfied with the constraints of patriarchal norms.

Chen, a photography student at an art school in Shanghai, noted that her male professors often doubted her ability to keep up with male students due to her petite stature.

Chen felt frustrated but could not express her emotions outwardly until she discovered Women’s Script.

“I feel I have gained tremendous power, and I believe many women need this strength,” Chen said.

A woman hand-embroiders characters of Women’s Script following the custom of the Third Day Letter at an exhibition in Hunan, China. (Photo: Hunan Today)

Chen shared her desire to create a documentary about feminism and serendipitously came across Women’s Script. While researching materials for her script, Chen realized that Women’s Script not only represents tragedies but also embodies women’s strength.

Since 2022, Chen has been promoting Women’s Script. She established an online Women’s Script group, organizing writing workshops and art exhibitions across various cities in China.

Lu Sirui, 24, who works in marketing and is a member of Chen’s Women’s Script group, shared: “At first, I only knew that it was a heritage of women, belonging solely to women. As I delved deeper, I realized it was a form of strength to confront social issues.”

She mentioned that such Women’s Script communities have supported her and many women in facing domestic violence, gender inequality, mother-daughter relationship issues, and various other challenges.

She added: “It is important for women to unite, and Women’s Script serves as a bond of sisterhood. It symbolizes the timeless and boundless power of women.”

Today, Women’s Script can be found in bookstores across China, advertised on public transport, at fair booths, as tattoos, art pieces, and even on everyday items like bowls, chopsticks, and hairpins.