The Ouroborous-3 rocket can self-ignite its HDPE plastic body, providing fuel for missions and reducing space debris.

A research team at the University of Glasgow has developed a rocket that can self-ignite its body as fuel and tested it at Machrihanish Airbase in the UK. The research was presented at the AIAA Science and Technology Forum in Orlando, Florida, USA, on January 10.

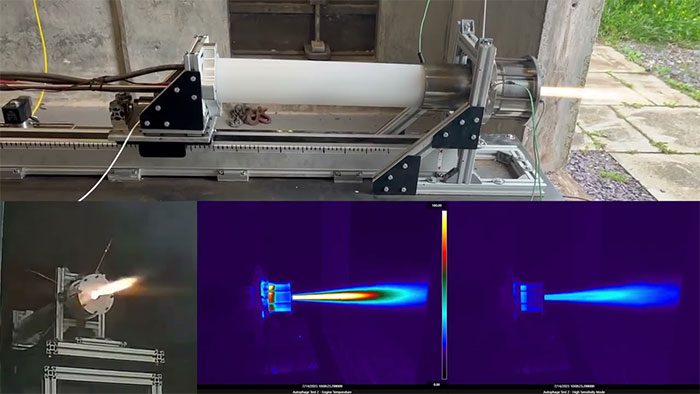

Prototype of the self-igniting rocket. (Video: University of Glasgow).

For seven decades, as humans have launched satellites, the space surrounding Earth has become cluttered with space debris. Fast-moving debris poses significant threats to satellites, spacecraft, and astronauts. While many expert groups are developing methods for space debris removal, Professor Patrick Harkness’s research team at the University of Glasgow has developed a rocket that uses its own body as fuel, thus eliminating the need to discard parts into space.

Harkness’s team collaborated with researchers at the National University of Dnipro in Ukraine to test the self-consuming rocket (a “self-eating” rocket). The concept of a self-consuming rocket was proposed and patented in 1938. Traditional rockets often carry empty fuel tanks that no longer serve any purpose, but a self-consuming rocket can utilize them to provide additional energy for missions. This capability allows the rocket to carry more cargo into space than traditional rockets, paving the way for launching multiple nano-satellites in one go instead of having to wait and divide into multiple launches.

The self-consuming rocket can use them to provide additional energy for missions.

Harkness’s team named their self-consuming rocket engine Ouroborous-3 and used high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipes as supplemental fuel to burn alongside the primary propellant – liquid propane and oxygen gas. The waste heat from the combustion of the primary fuel melts the plastic and feeds it into the combustion chamber along with the main fuel.

The prototype rocket was first tested in 2018. However, with the collaboration of Kingston University, the research team has now demonstrated that stronger liquid propellants can be used and that the plastic pipes can withstand the forces that propel them into the rocket engine.

In tests conducted at Machrihanish Airbase, the Ouroborous-3 generated a thrust of 100 Newtons. The rocket prototype also showed stable combustion, with the body providing one-fifth of the total fuel needed. This is a crucial step in developing a rocket engine that can operate effectively in real-world conditions.