When we think about the habitability of exoplanets, the role of magnetic fields in maintaining a stable environment is something to consider alongside factors like the atmosphere and climate.

Radiation belts are magnetic structures shaped like rings that envelop a planet, filled with electrons and high-energy charged particles.

First discovered around Earth in 1958 with the Explorer 1 and 3 satellites, radiation belts are present throughout the Solar System: all large-scale magnetic planets—Earth, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—possess them. However, until now, no radiation belt has been clearly observed beyond our Solar System.

The magnetic field helps preserve life on a planet – (Image: Internet).

Today, a small group of astronomers led by Melodie Kao, formerly from Arizona State University and now a researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, along with Professor Evgenya Shkolnik from the U.S. Institute for Earth and Space Exploration, discovered the first radiation belt outside our Solar System. The results were published in the journal Nature on May 15.

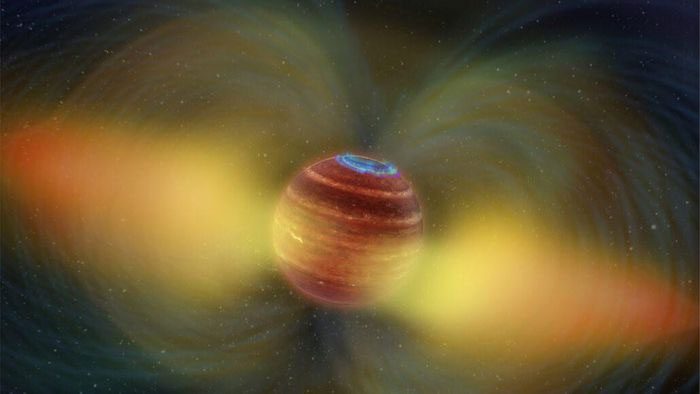

The discovery was made around the “brown dwarf” LSR J1835+3259, which is roughly the size of Jupiter but much denser. Located just 20 light-years away in the Lyra constellation, it is not massive enough to be a star but too heavy to be a planet. Because radiation belts have never been clearly seen beyond our Solar System, we do not know if they can exist around other objects like exoplanets.

Professor Evgenya Shkolnik, who has researched magnetic fields and the habitability of exoplanets for many years, stated: “This is an important first step in searching for more such objects and honing our skills to seek out increasingly smaller magnetic fields, ultimately allowing us to study Earth-sized habitable planets.”

Although invisible to the human eye, the radiation belt discovered by this research team is a gigantic structure. Its outer diameter extends at least 18 times the diameter of Jupiter, with the brightest regions inside measuring nine times Jupiter’s diameter (for reference, the diameter of the Sun is only 10 times that of Jupiter). Composed of particles moving near the speed of light and emitting strongly at radio wavelengths, this newly discovered radiation belt outside the Solar System is nearly 10 million times more intense than that of Jupiter. At the same time, it is also millions of times brighter than Earth and contains more high-energy particles than any planet in the Solar System.

The research team captured three high-resolution images of radio-emitting electrons trapped in the magnetic field of the brown dwarf LSR J1835+3259 over the course of a year using a renowned observational technique that we used to photograph the black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

By coordinating 39 radio dishes spanning from Hawaii to Germany to create an Earth-sized telescope, the team resolved the dynamic magnetic environment of the brown dwarf, known as the “magnetosphere”, allowing them to observe the magnetic field of an object outside the Solar System for the first time. They could even see the shape of this magnetic field clearly enough to infer that it likely has a dipole structure similar to that of Earth and Jupiter.

Professor Jackie Villadsen from Bucknell University, a member of the research team, stated: “By combining radio dishes from around the world, we could create extremely high-resolution images to see things that no one has seen before. The strength of our observational system can be compared to a person in Washington D.C. being able to read the top line of an eye chart located in California.”

In fact, Kao’s team had previously suspected they would find a radiation belt around this brown dwarf. At the time the team made these observations in 2021, radio astronomers had detected LSR J1835+3259 emitting two types of detectable radio emissions. Kao herself confirmed six years ago, while in another research group, that its periodic pulsing radio emissions, similar to a lighthouse, were auroras at radio frequencies.

However, the brown dwarf LSR J1835+3259 also has more stable and weaker radio emissions. Data showed that these fainter emissions could not come from stellar flares and closely resembled the radiation belts of Jupiter.

This group’s discovery indicates that such phenomena could be more common than initially thought—not only occurring on planets but also on brown dwarfs, low-mass stars, and possibly even very massive stars.

The area around a planet’s magnetic field, or magnetosphere—including Earth’s magnetic field—can protect the atmosphere and surfaces of the planet from being ravaged by microwave particles from the Sun and space.

Kao remarked: “When we think about the habitability of exoplanets, the role of the magnetic field in maintaining a stable environment is something to consider alongside factors like the atmosphere and climate.”

In addition to the observed radiation belt, Kao’s team’s research indicates differences in the “shape” and spatial location of auroras (similar to Earth’s auroras) compared to the radiation belt from an object outside our Solar System.

Kao stated: “Auroras can be used to measure the strength of a magnetic field, but not its shape. We designed this experiment to introduce a method for assessing the shape of magnetic fields on brown dwarfs and ultimately on exoplanets.

The specific characteristics of each radiation belt tell us something about the energy source, magnetism, and particles of that planet: how fast it spins, how strong its magnetic field is, how close it is to its parent star, whether it has moons that could provide more particles, or whether there are ring systems like that of Saturn that could absorb them, etc. I am excited for the day when we can learn about exoplanets with magnetospheres, which means the potential for preserving life.”