Thanks to the use of the latest advanced imaging techniques, scientists at Stanford Medicine have mapped a part of the human body.

According to a study published in the journal Nature, researchers at Stanford Medicine conducted examinations of eight regions of the small intestine and colon from nine deceased organ donors.

The small intestine averages about 6 meters long, nearly four times the length of an average human. This is considered the largest internal organ in the human body.

Experts utilized a technology called CODEX (also known as code-based multiplexing) to capture images of these areas. Specifically, intestinal tissue was stained and washed multiple times with fluorescent antibodies that bind to proteins, facilitating easier imaging.

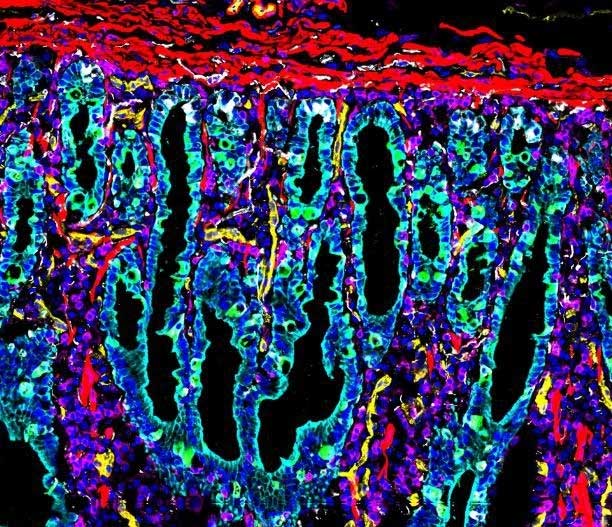

This is the first map of the human intestine. (Photo: Stanford Medicine).

By utilizing CODEX and imaging technologies, combined with new sequencing methods, scientists were able to map adjacent intestinal regions at the level of individual cells. This achievement had not been accomplished in previous studies.

In fact, when the intestines were mapped, experts identified 20 distinct neighborhoods of intestinal cells within the human digestive system.

Researchers found that these include epithelial cells that form the intestinal lining, connective tissue cells, nerve cells, immune cells, and blood vessels.

This detailed image shows muscle cells in red surrounded by bright red immune cells, along with cyan proteins and endothelial cells forming blood vessels (shown in yellow). (Photo: Stanford Medicine).

The research team hopes that these images will be used to aid in diagnosing conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and early-stage colorectal cancer. This way, doctors can compare and analyze images of healthy and unhealthy digestive systems.

Ultimately, the team of scientists aims to create a three-dimensional map of the intestine to gain a deeper understanding of the neural and vascular structures of the digestive system. This will assist in diagnosing and treating various gastrointestinal diseases.

For the first time, scientists map the human intestine

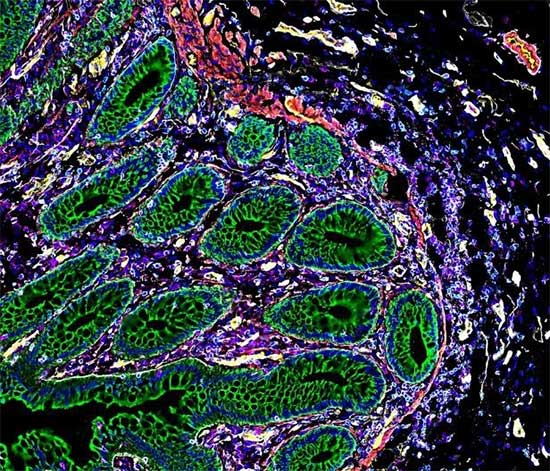

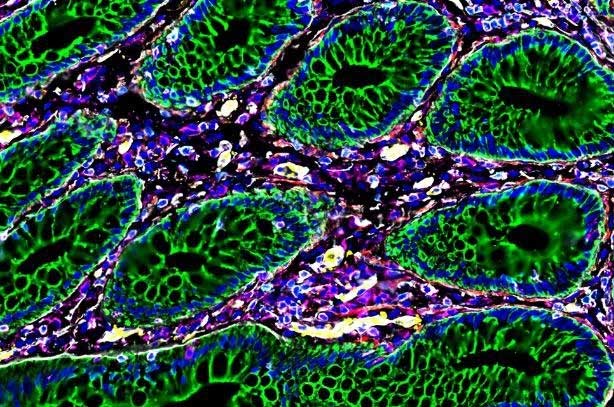

In this image, the regions marked in green are cytokeratins. These proteins allow the cells to withstand the mechanical stress of the digestive process. This type of protein is surrounded by immune cells (in bright red) and standard cell nuclei (in blue). (Photo: Stanford Medicine).

Professor Michael Snyder at Stanford Medicine stated: “This is the first time we’ve mapped the human intestine at a single-cell level. It feels like discovering a new planet, where we don’t know exactly what types of cells we will find or how they will be organized.”

The intestine contains many types of cells, including epithelial cells that form the intestinal lining, connective tissue cells, nerve cells, and immune cells. With the new maps, scientists can not only identify the location of each cell type but also determine other cells they are connected to.

Professor Garry Nolan at Stanford added: “Looking at the presence or absence of a single cell doesn’t tell us much. We need to look at how cells are interconnected to determine their function.”

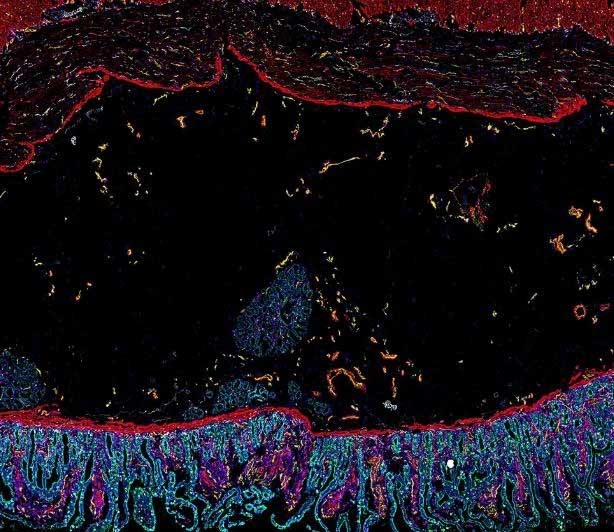

Close-up of proteins, bacteria, and immune cells. (Photo: Stanford Medicine).

In addition to creating a reference for healthy tissues, the new maps also reveal some intriguing clinical connections. For instance, researchers found that organ donors with higher body mass indexes had significantly increased levels of M1 macrophages, which are associated with inflammatory conditions.

Experts suggest that individuals with higher body mass indexes, particularly above certain thresholds, are at greater risk for gastrointestinal diseases. Many of these are linked to chronic inflammation.

In this study, all nine intestinal samples came from adult donors. Most were male and of Caucasian descent.

Professor Snyder stated: “One of our next steps is to increase the diversity of our samples. Our goal is to have a more comprehensive sample group that includes diversity in ethnicity and age groups.”