A rare fossilized plant has been preserved with leaves that exhibit a structure unlike any known plant species, providing evidence of the evolution of plant life.

New research reveals that this uniquely preserved plant fossil belongs to a peculiar shrub species unearthed in southeastern Canada. These plants are unlike anything scientists have previously encountered and could represent an example of evolutionary experimentation.

A computer-generated model illustrating the plant structure of Sanfordiaaulis, a species known from a 350-million-year-old fossil.

An earthquake that occurred 350 million years ago toppled trees and buried them in mud, leaving near-perfect impressions of their trunks and leaves in sediment at the bottom of what was then a lake. Geologists discovered the first fossilized tree while excavating a quarry in New Brunswick in 2017, and later unearthed four additional nearly identical specimens.

The lead author of the study, Robert Gastaldo, an emeritus professor of geology at Colby College in Maine, shared: “We were surprised; it is quite unusual to find a fossil plant species of tree size still with its leaves preserved attached to the trunk in a crown-like shape.”

Preserved leaves in fossil form, showing remnants of the canopy.

Typically, only the trunks of ancient trees are preserved in the fossil record. However, this new discovery reveals a dense canopy comprising over 250 leaves clustered around the top of a slender, unbranched trunk measuring about 30 inches (75 cm) in diameter and approximately 2.7 meters tall. According to the study published on Friday (February 2) in the journal Current Biology, the leaves can reach up to 9.8 feet (3 meters) in length and extend from the trunk in a “tightly coiled spiral.”

The researchers state in the study that the trees named Sanfordiaaulis likely developed this spiral structure to maximize the amount of sunlight captured by the leaves for photosynthesis. Their shorter stature also suggests that these trees represent some of the earliest examples of smaller plants growing beneath taller canopies.

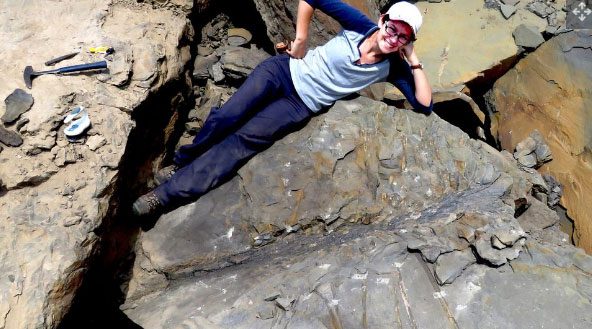

Olivia King, a participant in the discovery of the new fossil, reclining beside one of the Sanfordiaaulis specimens.

Gastaldo noted that reconstructing these trees “distorts our perception of how trees are organized and grow.” He continued: “Their growth structure is similar, but distinctly different from two tree models found in today’s tropics,” which include a small number of ferns, gymnosperms (seed plants with exposed seeds), and flowering plants. However, these modern trees have fewer leaves in their canopies, ranging from 15 to 20 leaves for ferns and palm trees, he added.

Gastaldo mentioned that Sanfordiaaulis might stand out among the Carboniferous vegetation (359 million to 299 million years ago) similar to Aloidendron dichotomum, formerly known as Aloe dichotoma and the modern baobab Adansonia.

He stated: “We regard these as oddities compared to the rest of the angiosperms (flowering plants). Such oddities existed for a long time in other plant groups before flowering plants appeared on the planet, but we have no clues unless a very rare event occurs to preserve an entire plant species.

According to the study, plant diversity was very high during the Devonian (419 million to 359 million years ago) and the Carboniferous. Gastaldo suggested that these unusual fossils could serve as an example of an evolutionary experiment from this period. He said: “The evolutionary process of the plant kingdom has undergone many different forms of experimentation that succeeded for several million years or more, but did not withstand the test of time.”