Plant fossils from over 400 million years ago exhibit irregular structures, differing significantly from most plants today that follow the Fibonacci spiral.

The arrangement of leaves on branches, the structure of pine cones, the petals of sunflowers, and the scales of pine cones are excellent examples of mathematical patterns found in nature. A common characteristic among most plant species today is their spiral structures, adhering to the Fibonacci sequence.

These spirals, simply known as Fibonacci spirals, are prevalent in plants and have captivated famous scientists, from Leonardo da Vinci to Charles Darwin.

The prevalence of Fibonacci spirals in today’s plants is regarded as a representation of ancient and highly conserved traits, appearing from the early stages of plant evolution to the modern era.

However, a new discovery by biologist Sandy Hetherington from the University of Edinburgh and paleobotanist, PhD student Holly-Anne Turner at University College Cork could overturn that understanding.

The research team examined the spirals on the leaves and reproductive structures of a fossilized plant dating back 407 million years. They were astonished to find that all observed spirals in this unique species did not follow the same rule. Today, there are very few plants that do not conform to the Fibonacci spiral.

What is the Fibonacci Spiral?

Spirals are commonly found in nature, visible in leaves, animal shells, and even in the double helix structure of human DNA. In most cases, these spirals relate to the Fibonacci sequence—a series of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21…).

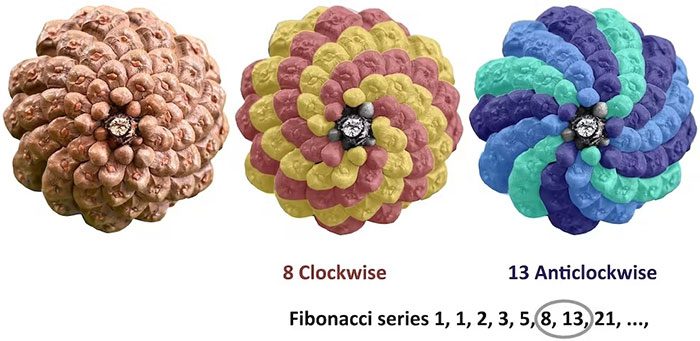

Patterns commonly seen in plants can even be recognized by the naked eye. If you pick up a pine cone and look at the base, you can see the scales forming a spiral converging at the point attached to the branch.

A digitized image of a pine cone, colored to identify 8 clockwise Fibonacci spirals and 13 counterclockwise Fibonacci spirals. (Photo: Sandy Hetherington).

At first glance, you will notice spirals in one direction. But upon closer inspection, you can see both clockwise and counterclockwise spirals. If you count the number of spirals in both directions, in many cases, the number of spirals will be an integer in the Fibonacci sequence.

This is not an exception. According to a study analyzing 6,000 pine cones, 97% exhibit Fibonacci spirals. Additionally, this structure is common in other plant organs such as leaves and flowers.

If you look at the top of a tree, such as the shoots of the Araucaria araucana, you can see leaves arranged in a spiral starting from the top and gradually curling around the trunk. A study of 12,000 spirals from over 650 plant species found that Fibonacci spirals were present in over 90% of cases.

Based on the frequency of occurrence in living plant species, it has long been believed that Fibonacci spirals are an ancient and highly conserved trait across all plant species.

Non-Fibonacci Spirals in Primitive Plants

To test this hypothesis, scientists studied the arrangement of leaves and reproductive structures in ancient plant groups related to modern lycopods (Lycopodiopsida).

Specifically, Sandy Hetherington and Holly-Anne Turner examined the fossils of the extinct plant Asteroxylon mackiei. The fossils are held in museum collections in England and Germany, originally collected from Rhynie chert—a prehistoric sedimentary deposit located in northern Scotland.

Holly-Anne Turner, the lead author of the study, creating 3D digital models of Asteroxylon mackiei at the University of Edinburgh. (Photo: Luisa-Marie Dickenmann).

The scientists photographed thin sections of the fossils and then used digital reconstruction techniques to visualize the arrangement of Asteroxylon mackiei leaves in 3D and identify the spirals.

Based on this analysis, the authors discovered that the leaf arrangement in Asteroxylon mackiei was highly variable. In fact, non-Fibonacci spirals were the most common arrangement.

The discovery of non-Fibonacci spirals in such an ancient fossil is surprising, as they are quite rare in most living plant species today.

Differentiated Evolutionary History

These findings change our understanding of Fibonacci spirals in terrestrial plants. They demonstrate that non-Fibonacci spirals existed in ancient lycopods, reversing the notion that all leaf-bearing plants began growing leaves according to the Fibonacci pattern.

A reconstructed image from the fossil of Asteroxylon mackiei. (Photo: Hetherington).

Furthermore, the new discovery indicates that the evolution of leaves and Fibonacci spiral structures in lycopods has a distinct history compared to other living plant groups today, such as ferns, conifers, and flowering plants. It suggests that Fibonacci spirals arose multiple times, independently throughout the evolutionary history of plants.

This work also adds another piece to the important evolutionary question: Why are Fibonacci spiral structures so prevalent in today’s plants?

This question continues to spark debate among scientists. Various hypotheses have been proposed, including maximizing the amount of light each leaf receives or efficiently packing seeds.

The findings of Sandy Hetherington and Holly-Anne Turner open up further insights into fossils, demonstrating that plants like mosses may provide crucial clues in the search for answers.