Approximately 200 ancient stone fortresses in Europe exhibit vitrification due to heating, puzzling archaeologists for the past 250 years.

During the Bronze Age and Iron Age, Europeans constructed numerous stone fortifications on hills. About 200 such structures show signs of having been affected by high temperatures. The walls were burned at such high temperatures that the stones partially melted and fused together, a phenomenon known as vitrification. For the past 250 years, vitrified forts have remained a mystery to archaeologists.

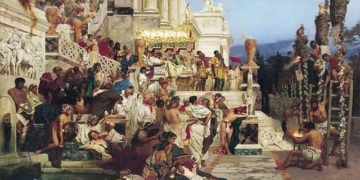

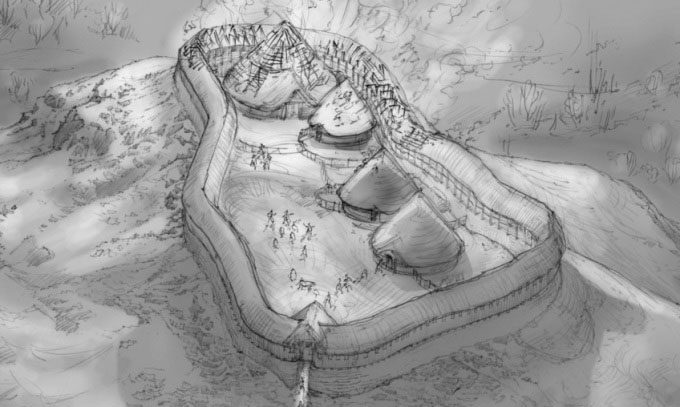

Illustration of the vitrified fort Dun Deardail in Glen Nevis, Scotland. (Photo: Scotsman).

Initially, the vitrification process was thought to be a result of past battles. However, it is peculiar that vitrification is the only thing holding the stone walls together. These forts contain no binding materials such as mortar or lime. Some evidence suggests that the stones were stacked in a dry state and then intentionally burned, causing them to fuse into a solid mass.

Currently, scientists propose two hypotheses. The first hypothesis suggests that the melting of the stone walls was an unintended consequence of another activity, such as metalworking, kiln firing, or signaling fires. The second hypothesis posits that this was the result of an extraordinary construction effort.

In a pioneering experiment conducted by engineer Wallace Thorneycroft and archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe in the 1930s, a wall measuring 1.8 m x 1.8 m was built using stones interspersed with horizontal wooden beams and then burned. The fire lasted for three hours, after which the wall collapsed. Thorneycroft and Childe found that the rubble had vitrified with wooden fragments mixed in. They estimated that the fire reached temperatures of about 1,200 degrees Celsius.

According to another study by expert E. Youngblood at the Smithsonian Institution and colleagues, published in the journal Archaeological Science in 1978, burning a wall mixed with wood was insufficient to explain the intense vitrification of the ancient forts. The research team suggested that the fire causing this vitrification could have burned for several days, maintaining temperatures above 1,000 degrees Celsius.

This could only occur if the fire was controlled, for instance, by filling the gaps between the stones in the wooden frame with earth, clay, and flammable materials like peat. It is unlikely that the walls were unintentionally burned or set ablaze by enemies, indicating that the act of burning was deliberate. But why would ancient people do this?

Vitrified fort at Sainte-Suzanne, France. (Photo: jp.morteveille/Wikimedia).

One plausible explanation is to increase the durability of the stone structure. This explanation has been rejected by many researchers because heating typically weakens stone structures, creating small cracks due to the differential expansion of the stone. However, a study published in the journal Archaeological Science in 2016 argued that this does not apply to sandstone—a common building material for forts. This type of stone increases in strength under heat as the small particles within the stone combine into a solid glass mass. If this is correct, the ancient vitrified forts are indeed remarkable constructions.

Initially, researchers believed that vitrified forts existed only in Scotland. However, they have also been found in several other areas of Western and Northern Europe. There are over 200 such structures across Europe, with 70 located in Scotland.