Like any pirate, William Dampier (1651 – 1715) was fascinated by gold. However, what captivated him even more was the natural world. With a thirst for exploration, he overcame numerous challenges, becoming the first natural scientist and leaving behind a colossal legacy of knowledge for future generations.

Dampier’s natural exploration legacy is a great treasure. (Photo: Classicalimages.com).

Love for Nature Over Gold

Dampier was born and raised in East Coker, England, the second son of a tenant farmer. Orphaned at an early age, he was cared for by his mother, who ensured he received an education, allowing him to read and excel in mathematics. In 1673, at the age of 22, Dampier joined the Royal Navy but had to leave early due to a serious illness.

Feeling disheartened, Dampier traveled to North America in search of fortune, trying various jobs but finding none to his liking. Suddenly, he jumped aboard the ship of pirate Bartholomew Sharp (1650 – 1702) and became a pirate.

Initially, Dampier refused to acknowledge his piracy. In his journal, he wrote that he only boarded a merchant ship to practice woodcutting. This ship had 250 crew members, and they “were either chopping trees, sawing, cutting logs into neat pieces, or collecting tree sap…” Furthermore, they had gunpowder and often used it indiscriminately.

The portrait of the first naturalist, William Dampier. (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

Although assigned to saw wood, Dampier rarely used the saw. Almost all day, he wandered in the forest, observing various plant species and watching animals. Of course, the pirates didn’t let him “sit idle,” but with his cloud observation skills and wind direction recognition, Dampier soon found a “high-paying, light job” in weather forecasting. Thanks to his tendency to hide and explore, he also accidentally discovered enemy positions, which led to him being assigned the role of a scout.

The most brutal raid while Dampier was aboard Sharp’s ship was the attack on the fort protecting the town of Alvarado in Veracruz. More than ten pirates were killed, but when they entered the town, every house was “abandoned” as the residents fled with their riches. While other pirates were angry or desperate, Dampier was overjoyed to find domesticated parrots with bright yellow and red feathers before him.

In 1678, Dampier returned to England, marrying Judith, a maid of the Duchess of Grafton. Just a few months after the wedding, he returned to North America to continue his pirating ways. For nearly the next 20 years, Dampier served under various pirate captains, and although he had to pillage like a pirate, he never ceased observing and researching the natural world, ultimately compiling his findings into his first book, A New Voyage Round the World.

Failed Commander and Great Naturalist

Dampier became a pirate as it was the only way he thought he could travel the world. (Photo: Sciencehistory.org).

The acclaim of A New Voyage Round the World absolved Dampier of his pirate crimes. It was regarded by the Royal Society as “the most fascinating and detailed account of people, places, objects, plants, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals.”

In 1698, Dampier was granted command of the Roebuck, a heavy warship with 12 cannons, by the Navy Board to explore the eastern coast of Australia under orders from King William III.

On January 14, 1699, Dampier set sail. On August 6 of the same year, he arrived in Western Australia and immediately began investigating and documenting the flora and fauna of Australia. Assisting him was his secretary and artist James Brand.

Throughout the last four months of 1699, Dampier and Brand actively explored islands, bays, and charted straits. In February 1701, the Roebuck encountered a storm and sustained severe damage. Dampier had no choice but to return to England. The result of over a year of natural investigation in Australia was a thick dossier, including records of flora and fauna, sea charts, monsoon data, and ocean currents.

Although much was lost when the Roebuck encountered disaster, he managed to retain some specimens, including many plant samples that Australia later borrowed from England in 1999 to commemorate the 300th anniversary.

In 1701, Dampier was appointed commander of the St George, a warship with 24 cannons and a crew of 120, to combat the Spanish. He engaged in several battles with the Spanish navy, but never achieved victory, ultimately returning to England in defeat in 1707.

In 1708, Dampier once again boarded a warship, this time as a crew member. However, he still did not achieve any notable victories against the Spanish navy. Around early 1715, he died under unclear circumstances, leaving behind only debts of nearly £2,000.

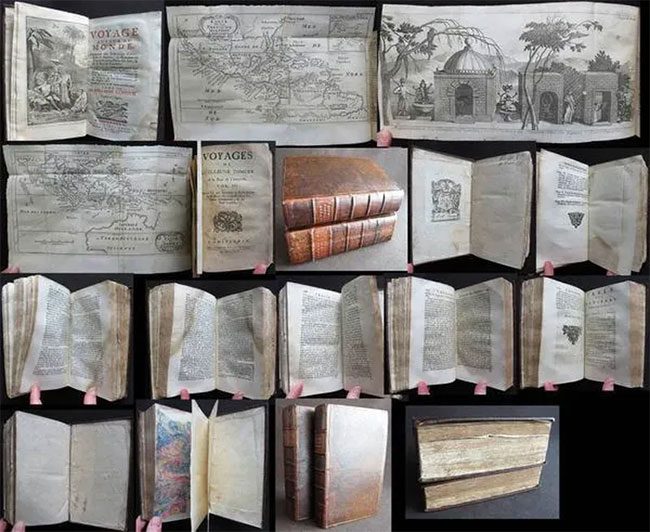

Contrary to his declining career as a pirate or naval officer, Dampier’s career as a naturalist was incredibly bright. In 1699, he published his second book, Voyages and Descriptions, providing additional information about his first circumnavigation of the globe, particularly his experiences in recognizing winds. He was the first to realize that tropical cyclones and hurricanes are the same phenomena, only differing in their names.

In 1703, Dampier published his third book, A Voyage to New Holland, recounting his adventures exploring Australia funded by the British government. Throughout his life, he circumnavigated the globe three times, comparing and contrasting the flora and fauna worldwide.

In addition to these three main works, Dampier also published several appendices and other books. Thanks to him, the contemporary world gained a deeper understanding of the seas and lands, animals and plants, cultures and geography… Even today, his legacy of natural and cultural exploration remains an endless source of knowledge and inspiration for researchers and creators.