Scientists have discovered that the concentrations of calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus in women’s bones are lower after giving birth. This change is permanent and irreversible.

One noticeable aspect of women after childbirth is the change in body shape, making them more prone to weight gain, and their skin tone may also appear different. Some individuals even experience slight changes in bone structure, with broader shoulders and hips. This is believed to be due to hormonal changes and skeletal adjustments during pregnancy and childbirth.

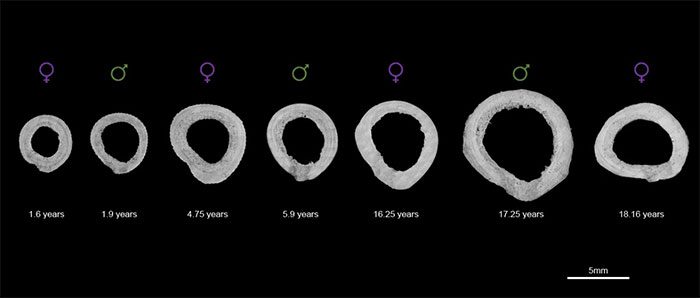

Microscopic cross-section images of 7 femurs identified by age and gender – (Image: Paola Cerrito/Timothy Bromage).

Few people realize that after each childbirth, not only does a woman’s external appearance change, but there are also significant internal changes in her bones.

A team of scientists from the Department of Anthropology at New York University (USA) has found that <strong,reproduction permanently alters women's bones in previously unknown ways. This discovery is based on the analysis of bones from primate species, clarifying earlier observations that childbirth can lead to permanent changes in the body.

Although previous studies have indicated that menopause can affect women’s bones, scientists have not fully understood how earlier life events, such as reproduction, might impact skeletal structure.

To shed light on this, the scientists examined the growth rates of the femurs of both male and female primates, tracking and recording information about their reproductive histories and correlating changes in bone composition with life events in these primates.

They also employed chemical composition measurement technology, utilizing electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis—a method for assessing the chemical composition of tissue samples—to calculate changes in calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, magnesium, and sodium concentrations in the bones of the primates.

The results showed that the concentrations of calcium and phosphorus in primates that had given birth were significantly lower than those in males and younger primates. The magnesium levels during the lactation period of these primates also decreased considerably.

Importantly, this change lasts a lifetime.

These changes further demonstrate that the skeletal system is not a static organ but a dynamic one that adjusts according to the events in an individual’s life.

The new study from New York University does not specify whether the deficiencies in calcium and phosphorus have overall health impacts on either primates or humans.

Instead, the changes in bone density after childbirth highlight the dynamic nature of bones, which continuously adjust and respond to physiological processes.