Methane is a greenhouse gas that accounts for nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Nearly 40% of human-caused methane emissions come from the extraction and use of oil, gas, and coal.

Satellite illustration monitoring methane. (Photo: MethaneSAT LLC).

Google plans to utilize satellite data, AI technology, and computing power to map methane emissions. Starting in March 2024, Google will use a satellite named MethaneSAT, which will orbit the Earth 15 times a day to monitor methane leaks from oil and gas companies, with hopes of making the findings public by the end of the year.

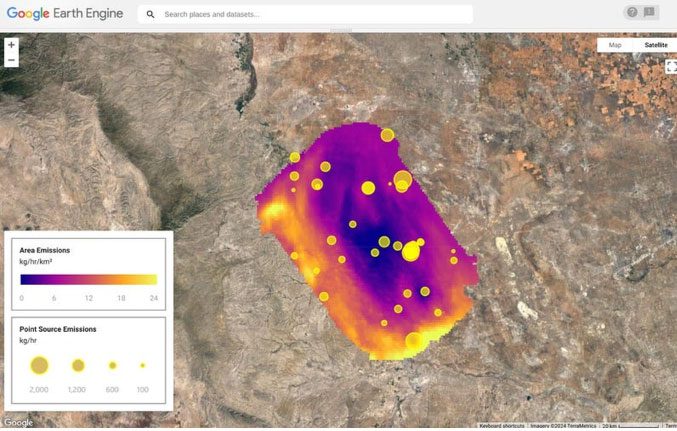

Google intends to use satellite data, AI technology, and computing power to map methane emissions. (Photo: Google).

This will be the result of a collaboration between Google and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) in the United States, marking a new era of accountability for global climate action.

Scientists say that reducing methane emissions is one of the fastest ways to slow down the climate crisis, as methane has a warming potential 80 times greater than carbon dioxide over a decade.

Dr. Steve Hamburg, EDF’s chief scientist and project director for MethaneSAT, stated, “The need for environmental protection is more urgent than ever, and reducing methane emissions from fossil fuel use and agriculture is the quickest way for us to slow the ongoing warming process.”

Agriculture has long been considered a major source of methane emissions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) argues that livestock farming is the largest source of methane emissions among human activities, followed by the energy sector.

Oil, gas, and coal extraction and use account for up to 40% of global methane emissions. The IEA suggests prioritizing the energy sector, as reducing methane leaks can enhance cost efficiency. Leaked gas can be captured and sold, and the technology to do this is relatively inexpensive. However, it is quite challenging to monitor methane in real-time.

The MethaneSAT is a next-generation satellite designed to detect methane sources almost anywhere in the world. When combined with Google’s computing technology and artificial intelligence, the data provided by this satellite will be invaluable for analyzing and mapping oil and gas infrastructure.

Traditionally, measuring methane leaks has been costly, requiring the use of aircraft and handheld infrared cameras. This method only provides a snapshot at a given time, and it takes years to compile and research before results can be published. Mapping oil and gas facilities is also difficult. The locations of drilling rigs, industrial pumps, and storage tanks change rapidly, necessitating frequent updates to the maps. A satellite can meet this requirement.

Using the same AI technology that Google employs to search for plants and roads, they can now monitor oil and gas infrastructure. MethaneSAT will continuously provide updated data to identify the most leak-prone machinery and facilities.

Yellow spots indicate sources, while purple, orange, and dark yellow spots indicate emission levels across a large area. (Photo: Google).

Global Commitment to Methane

This satellite is being launched as countries and oil and gas companies aim to significantly reduce methane emissions by 2030 to address the environmental crisis.

At the United Nations summit in Dubai in 2023, companies producing 40% of the world’s oil and gas pledged to eliminate nearly all methane leaks from their operations within this decade.

Previously, at least 155 countries signed the Global Methane Pledge, which calls for a 30% reduction in emissions. This commitment was announced in 2021, but since then, methane emissions have continued to rise.

To alter this emission trajectory, last year, the United States and Europe enacted regulations to reduce methane emissions from fossil fuel infrastructure. The European Union’s regulations have gone further by targeting imported oil and gas. Approximately 80% of the energy Europe uses is imported, including imports from the United States. By 2027, these import sources will be required to meet methane emission standards equivalent to those of Europe.

Dr. Hamburg mentioned that Japan and South Korea, both reliant on imported energy, are also moving towards establishing similar regulations.

“This means that reducing methane emissions is no longer just a legal issue but is becoming a competitive matter within the industry. To achieve real results, governments, the public, and industrial facilities need to know exactly how much methane is leaking, where it is coming from, who is responsible, and how it is changing over time. We need data on a global scale,” Dr. Hamburg emphasized.

By the end of this year, Google will publicly and freely provide this data on the Google Earth Engine platform.