-

Construction Period: 1956 – 1959

-

Location: New York, USA

Among the architects often referred to as “The Big Four“, the founding fathers of the Modernist Movement in architecture – Le Corbusier (Charles-Éduoard Jeanneret), Alvar Aalto, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright (FLW) – the latter is perhaps the most skilled in creatively utilizing geometric forms in his works. Whether in the masterful details of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1916-1922; demolished in 1968), his “Maya” geometries in the early houses he built in California like the Hollyhock House (1919-21), or the grid structures at 45-degree angles and hexagons found in some of his most famous homes, Wright proves himself a master in creating modular patterns and volumes.

Circles, as well as circular and often spiral forms, were favorites of Wright, evident from his unbuilt proposal in 1925 for the Sugar Loaf Mountain Observatory project.

|

|

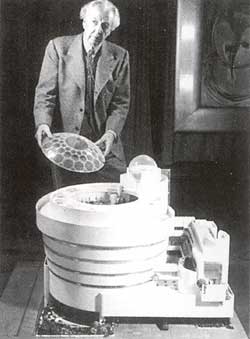

Frank Lloyd Wright with the model of the museum he designed, featuring a glass roof. |

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation in Milwaukee (1959-1961, built after Wright’s death) and the C.V. Morris shop (1948-1949) in San Francisco demonstrate Wright’s ability to transform what initially appears to be mechanical, bland geometry into dynamic, memorable spaces. Late in a long career filled with significant results, he lived from 1867 to 1959, Wright found a patron who consistently encouraged him. Solomon R. Guggenheim commissioned him to build a museum for a collection primarily of non-representational art gathered under the strict supervision of Countess Hilla Rebay, who later became the museum’s first director. This was also Wright’s first commission in New York City, with the design announced in 1944, but delayed due to World War II and the death of the founder five years later.

Location and Solution

The founder and director certainly had to tackle the unusual problem of displaying the collection. While conventional museum knowledge, even in the 1950s, seemed to favor a sequential arrangement of distinct gallery spaces, there were notable exceptions, especially in the U.S., such as Louis Kahn’s Yale Art Gallery in 1954.

Nearly 50 years earlier, Wright envisioned the massive volume of the Guggenheim Museum as well as hundreds of Roman halls illuminated from above that would later be constructed worldwide,

|

|

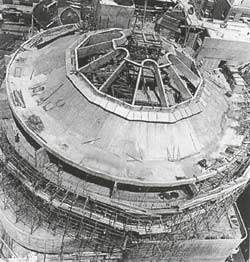

The museum under construction – reinforced concrete structure in place. |

in the design of an office building for the Larkin Order Shipping Company in Buffalo (1904, demolished in 1950). At the site on Fifth Avenue, between East 88th and West 89th Streets, overlooking Central Park, he was able to combine this concept with a compelling spiral geometry reminiscent of the historical ziggurats of the Near East, albeit in reverse. This comparison is reasonable, as Wright himself sketched this term on one of the museum’s cross-sections with a very elegant pencil drawing.

The museum was constructed of reinforced concrete, with 12 protruding structural sections connecting the corridor floors. Wright thoughtfully and skillfully designed the entrance with a low ceiling and relaxation areas, leaving visitors in awe as they stepped into a central volume branching upwards through four floors to the sky above. However, these floors were not conventional, but rather individual spiral ramps, lying on sloped walls that display most of the art collection.

Wright intended for art viewers to take an elevator to the highest floor and then descend the spiral ramp, occasionally stopping to view art displayed in less impressive rectangular exhibition rooms that open on each level.

|

|

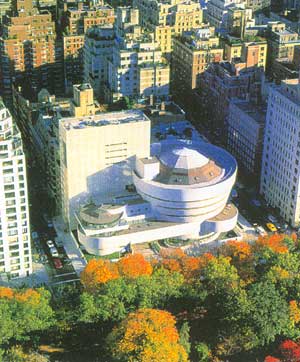

The museum is located right in the heart of New York City, directly across from Central Park. The rear extension was completed in 1992. |

There was also the option to ascend the ramp right from the entry level. In both cases, visitors would encounter a completely characteristic architectural paradox, based on Wright’s study that the Guggenheim was not the appropriate context for art. Should the paintings be displayed by hanging them horizontally or at a 10-degree angle on the ramp? Moreover, the sloping walls tend to display artwork as vertical planes, not relying on the usual framing seen on walls. The significance of each painting is further emphasized by the vertically protruding sections that form an integral part of the building’s structure, thus tending to fragment the continuous display.

These debates and many other opinions continue – since the inauguration of the Guggenheim Museum in October 1959. In 1992, the New York architects Gwathmey Siegel & Associates largely referenced Wright’s volumetric concept, creating much-needed additional corridor space and convenient museum management conditions. The recently constructed façade elevator has elevated the Guggenheim Museum’s amenities to international standards and remains a “must-see” destination for both domestic and international visitors. Some critics, including British commentator Bernard Levin, have affectionately described the museum as Wright’s ultimate practical joke on humanity, but the Guggenheim Museum continues to delight us as an opulent architectural space, as well as a venue with a world-class art collection.

Facts and Figures:

-

Ramp Width: 3m

-

Typical Ceiling Height: 2.9m

-

Exterior Finish: Concrete with cement & crushed marble plaster.

The stunning view straight up towards the sky,

and the spiral ramp going down. (Photo: lib.vt.edu)