Scientists Suggest That Extinct Pathogens Led to the Collapse of Ancient Civilizations.

Thousands of years ago, across the Eastern Mediterranean, many Bronze Age civilizations underwent a significant downturn at the same time.

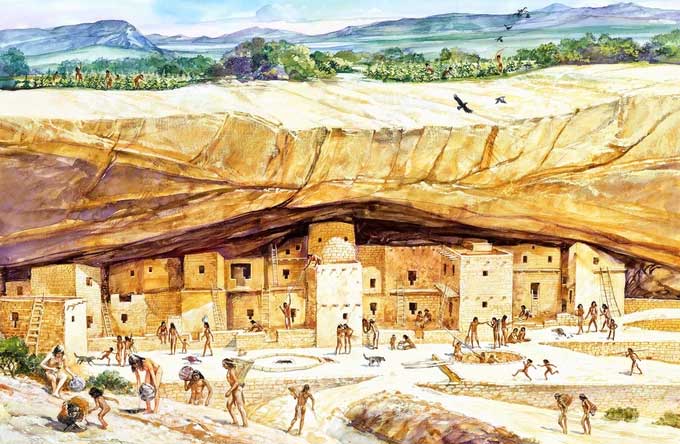

Alongside climate change and migration, disease also contributed to the collapse of many ancient civilizations (Photo: History).

The Ancient Egyptian Kingdom and the Akkadian Empire both fell during a widespread social crisis throughout the ancient Near East and Aegean, characterized by population decline, frozen trade, and significant cultural changes.

As is often cited, the primary reasons for this collapse are climate change and the loyalty of generals to the kings of these civilizations. However, scientists have recently uncovered a new culprit through the study of several ancient human remains.

A research team led by paleogeneticist Gunnar Neumann from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany analyzed skeletons excavated from a burial site in the Hagios Charalambos Cave on the island of Crete, Greece, and found genetic evidence of the bacteria responsible for two of history’s most significant diseases – typhoid fever and plague.

According to experts, the spread of diseases caused by these pathogens can no longer be dismissed as a contributing factor to the widespread social changes around 2200 to 2000 BCE.

“The emergence of these two harmful pathogens at the end of the early Minoan period in Crete emphasizes the need to reintegrate infectious diseases as a supplementary factor that may have contributed to the transformations of early complex societies in the Aegean and beyond,” the authors stated.

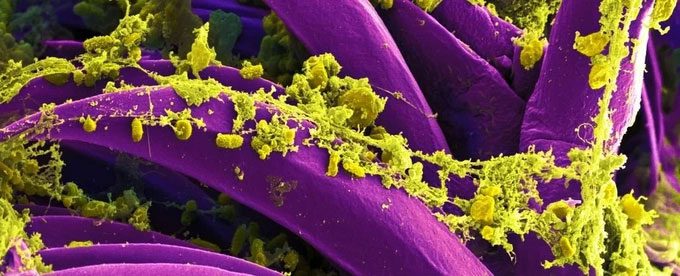

Yersinia pestis is the bacterium that causes plague, resulting in tens of millions of deaths primarily during three catastrophic global pandemics spanning centuries.

Thus, it is challenging to assess its impact before the onset of the Justinian plague, which began in 541 CE. However, thanks to recent advancements in science and technology, particularly in the recovery and sequencing of ancient DNA from old bones, some lost history is being revealed.

Experts suspect that this bacterium has been infecting humans since at least the Neolithic period.

Last year, scientists revealed that a hunter-gatherer from the Stone Age likely died from plague, well before we had evidence of the disease and its spread into a pandemic.

However, the genetic evidence recovered so far has primarily come from colder regions. Little is known about its impact on ancient societies in warmer climates, such as those in the Eastern Mediterranean, due to DNA degradation at higher temperatures.

The bacterium Yersinia pestis is responsible for the plague (Photo: NIH).

Therefore, Neumann and his team excavated bones recovered from a site on the island of Crete known for its stable and cool conditions. They recovered DNA from the teeth of 32 individuals who died between 2290 and 1909 BCE and found genetic data indicating the presence of the bacteria.

This included Yersinia pestis and two lineages of Salmonella enterica – a type of bacterium often causing typhoid fever. This discovery indicates that both pathogens were present at this time and could have been transmitted in Bronze Age Crete.

The challenge in this research is that each lineage (of the bacteria) identified is now extinct, complicating the identification of infectious diseases that might have affected the communities at that time.

The lineage of Yersinia pestis they discovered likely could not be transmitted through fleas – one of the characteristics that made other bacterial strains highly transmissible among human populations.

Flea vectors carry versions of the plague; humans become infected when the bacteria enter the lymphatic system through a bite. Thus, the transmission route of this ancient bacterium may differ and could cause a different form of plague.

Researchers noted that the Salmonella enterica strains also lack key features that contribute to severe illness in humans, meaning the virulence (the method by which the bacteria initiate infection and cause disease) and transmission routes of both pathogens remain unclear.

However, the findings indicate that they existed and circulated, particularly in densely populated areas of Crete, potentially leading to widespread outbreaks.

While it is uncertain whether Yersinia pestis or Salmonella enterica were the sole culprits behind the observed social changes in the Mediterranean at the end of the 3rd millennium BCE.

The authors suggested: “We propose that evidence from the studied ancient DNA carrying infectious diseases should be regarded as a supplementary contributing factor leading to the collapse of civilizations, alongside climate issues and migration.”

Because diseases like plague and typhoid do not leave traces on bones, they are not often recorded in the archaeological record.

The research team suggests that more detailed genetic screening of many ancient remains from the Eastern Mediterranean could help uncover the extent of these diseases’ impact on the civilizations living there.

The study has been published in the journal Current Biology.