This waterfall is renowned as the highest in the world, with a flow rate nearly 25 times that of the Amazon River, but unfortunately, it is very difficult to witness it in person.

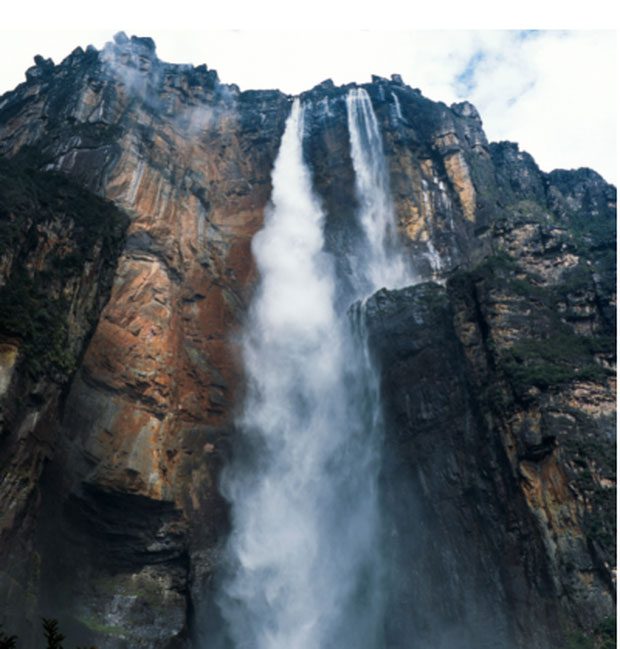

If someone were to ask which waterfall is the highest in the world, many would immediately think of Angel Falls in Venezuela. But is it really the tallest waterfall on Earth?

To be precise, Angel Falls in Venezuela is not the highest waterfall in the world. (Image: Baidu)

In fact, Angel Falls is considered the tallest waterfall above ground. However, beneath many ocean regions, there are numerous waterfalls that not everyone is aware of. Considering these underwater waterfalls, Angel Falls can no longer hold the top position. Instead, a waterfall located beneath the Denmark Strait is recognized as the highest underwater waterfall in the world. This waterfall has even been officially recognized by the World Record Union (WorldKings). So, what is this waterfall?

The “Hidden” Waterfall

This waterfall is located in the western part of the Denmark Strait in the Atlantic Ocean, between Iceland and Greenland. Scientists have named this gigantic waterfall the Denmark Strait cataract. It is also referred to as the Denmark Strait glacial melt.

The Denmark Strait waterfall has been confirmed as the highest underwater waterfall in the world. (Image: Baidu)

On April 10, 2021, based on the world record proposal from the Europe Records Institute (EURI) and decision number WK/USA.INDIA/679/2021/No.135, the World Record Union (WorldKings) officially announced the Denmark Strait waterfall as the highest underwater waterfall in the world on April 10, 2021.

This waterfall has a width of approximately 200 meters. It descends 3,505 meters from the Greenland Sea to the Irminger Sea, making it three times taller than Angel Falls. It averages a flow of 5 million cubic meters of water per second, nearly 25 times the flow rate of the Amazon River.

More than 100 years ago, scientists discovered giant waterfalls beneath some oceans. However, it wasn’t until after the 1960s, with advancements in science, that they began to study this peculiar phenomenon.

During a measurement of ocean current speed, a team of oceanographers from Greenland accidentally discovered this underwater waterfall. (Image: Baidu)

During a measurement of ocean current speed along a waterway off the coast of Greenland, a team of oceanographers stumbled upon the hidden Denmark Strait waterfall beneath the seabed. At that time, they had lowered a current meter to the ocean floor and noticed that the readings were extremely chaotic.

After calculations and real observations, they realized that the chaotic current was caused by the water. From the underwater cliffs, they discovered a massive waterfall. Unfortunately, because this waterfall is hidden beneath the ocean’s surface, those who love travel and exploration find it very difficult to witness the Denmark Strait waterfall in person without technological assistance.

The special feature of the Denmark Strait waterfall is its formation. This waterfall occurs due to the density difference between the water regions of the Greenland Sea and the Irminger Sea. Because molecules in cold water are less active and occupy less space than in warm water, they are denser. Therefore, when the two bodies of water meet, the colder, denser water flows downward beneath the warmer, less dense water.

This underwater waterfall helps maintain the salinity and climate of the ocean. (Image: Baidu)

Of course, waterfalls always have cliffs or slopes, and the Denmark Strait is no exception. A slope of 3,500 meters at the ocean floor near the southern tip of Greenland was formed by a glacier 11,500 to 17,500 years ago during the last Ice Age. The water at the ocean floor flows southward through the strait, rushing over the edge of the slope and cascading down its side, creating a waterfall beneath the warmer surface water of the Irminger Sea.

Even though the ocean floor descends more than 3,500 meters, the overflowing water is only about 2,000 meters high, double the height of Angel Falls, as it pours into a deep lake containing cold, dense water. This waterfall is impressive because, unlike waterfalls on land, according to Mike Clare, head of the marine geological systems group at the UK National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, for example, the flow is as wide as the Denmark Strait, meaning it spreads over 480 km of the ocean floor. As a result, the water flows down at a rate of only about 0.5 m/s, much slower than walking speed and far less than the flow rate at Niagara Falls (109 km/h) or 30.5 m/s.

The cold water flowing through the Denmark Strait is part of the ocean current system known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which brings warm water northward and cold water southward in a long circular path in the Atlantic Ocean. After leaving the Denmark Strait, the cold water continues its journey southward to Antarctica, gradually warming and rising to the surface (known as upwelling) before returning to complete the cycle in the Arctic.

Although the Denmark Strait waterfall lies at the ocean’s bottom and seems unrelated, it quietly affects our lives. This underwater waterfall plays a crucial role in maintaining the salinity and climate of the ocean. It also influences marine biology. Specifically, the Denmark Strait waterfall promotes a continuous flow of cold, saline seawater from the Arctic Sea to warmer regions near the equator.

The formation of underwater waterfalls also maintains the balance of deep seawater while impacting climate change and biological growth.

Aside from the Denmark Strait waterfall, there are other underwater waterfalls around the world, such as the Faro waterfall in Iceland, the deep plain waterfall in Brazil, and waterfalls in the South Shetland Islands, among others.