Today, nuclear energy is a concept that is no longer unfamiliar to many people. Alongside fusion energy, solar energy, and wind energy, it is predicted to be a high-performance energy source of the future, aimed at replacing fossil fuels to limit greenhouse gas emissions, reduce pollution, and more. Throughout its development history, nuclear energy has had diverse applications, from energy production and weapon manufacturing to serving various scientific research endeavors. Now, let’s turn back to the year 1789 with the German chemist, Martin Klaproth…

Discovery of Natural Uranium Atoms

Uranium was first discovered in 1789 by the German chemist Martin Klaproth, and it was named after the planet Uranus.

Martin Klaproth, the German chemist who first discovered Uranium in 1789

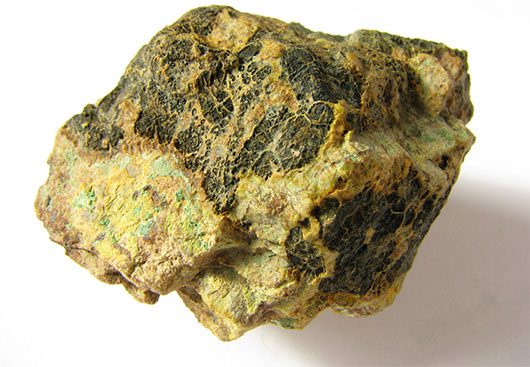

Ionizing radiation was discovered in 1895 by Wilhelm Röntgen during an experiment where an electric current passed through a glass vacuum tube, creating continuous X-rays. Following this, in 1896, Henri Becquerel discovered that pitchblende ore (a type of mineral ore containing radium and uranium) could darken photographic plates. He studied this phenomenon and demonstrated that it was due to beta radiation (electrons) and alpha particles (helium nuclei) being emitted.

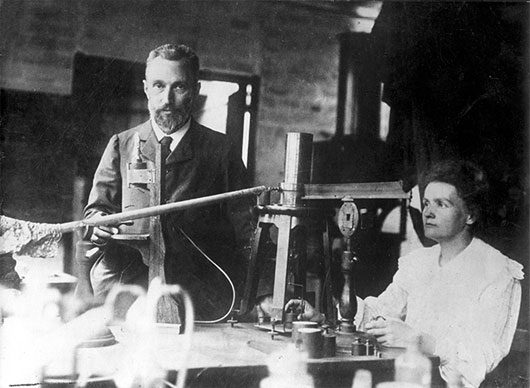

Later, French physicist Paul Villard discovered a third type of radiation from pitchblende: gamma rays, which are similar to X-rays. In 1896, Pierre and Marie Curie coined the term “radioactivity” to describe this phenomenon. Two years later, in 1898, they isolated Polonium and radium from pitchblende. In 1898, Samuel Prescott discovered that radiation could destroy bacteria in food.

Pierre and Marie Curie coined the term “radioactivity” to describe the phenomenon of nuclear decay

In 1902, New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) demonstrated that radioactivity is a spontaneous event, with alpha or beta particles emitted from the nucleus creating various elements. He (along with Soddy) proposed the theory of radioactive decay and demonstrated the formation of helium during this process. He is regarded as the “father” of nuclear physics for proposing the planetary model of the atom, laying the groundwork for modern atomic theories. From 1919, he worked at Cambridge, where he successfully carried out an experiment firing an alpha particle into a nitrogen molecule, observing that the nitrogen nucleus underwent a rearrangement and transformed into oxygen.

Pitchblende, a type of mineral ore containing radium and uranium in nature

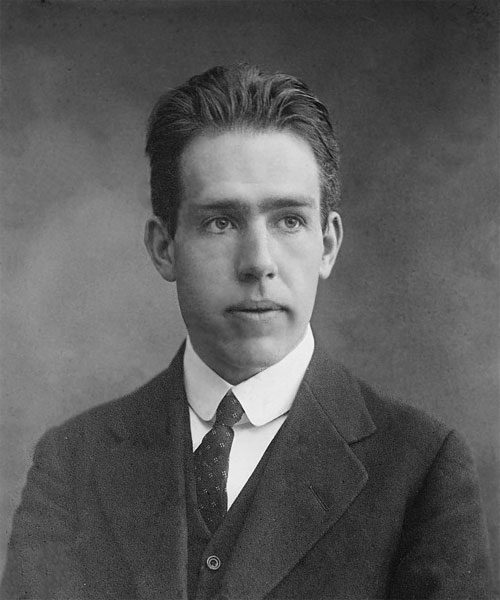

Niels Bohr (1885-1962), a Danish physicist, also made significant contributions to our understanding of the atom and the distribution of electrons around the nucleus during the 1940s. Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1922 for his important contributions to atomic research and quantum mechanics, and he is considered one of the most renowned physicists of the 20th century.

Niels Bohr (1885-1962), the Danish physicist who contributed significantly to our understanding of the atom and electron distribution around the nucleus in the 1940s

By 1911, British physicist Frederick Soddy (1877-1956) discovered that natural radioactive elements had several different isotopes (radioactive nuclides). Also in 1911, Hungarian chemist George Charles de Hevesy (1885-1966) utilized isotopes as labeled atoms to study chemical processes. An interesting point in Hevesy’s career was when Germany invaded Denmark; he dissolved the Nobel Prize medals of James Franck and Max von Laue in aqua regia so they would not fall into Nazi hands. After the war, he returned and used the preserved solution to precipitate the dissolved gold, which was later returned to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to mint new medals for Franck and Laue.

In 1932, James Chadwick discovered the existence of the neutron. Also in 1932, Cockcroft and Walton created a transformed nucleus by bombarding atoms with accelerated protons. Later, in 1934, Irene Curie and Frederic Joliot discovered nuclear transformations during bombardment that produced artificially radioactive isotopes. A year later, Italian physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-1954) found that using neutrons instead of protons for bombardment could produce many more artificially radioactive isotopes. Fermi made significant contributions to the development of beta decay and the first nuclear reactor created by humanity.

By the end of 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn (1879-1968) and Fritz Strassmann (1902-1980), in an experiment demonstrating nuclear fission, showed that they had created barium atoms with a mass that was half of the original uranium mass. Subsequently, Swedish physicist Lise Meitner (1878-1968) and her nephew Otto Frisch demonstrated that the nature of the fission process was due to the nucleus retaining neutrons, which caused strong vibrations in the nucleus, leading it to split into two unequal parts. They also estimated that the energy released from nuclear fission could reach approximately 200 million volts. Frisch continued to verify and confirm this figure in January 1939.

At the same time, Frisch’s verification confirmed Albert Einstein’s prediction about the relationship between mass and energy, which had been published over 30 years prior, in 1905.

Harnessing Energy from Nuclear Fission

The successes in nuclear fission experiments conducted by Frisch and other scientists in 1939 attracted many other scientists to pursue laboratory research. Subsequent studies by Hahn and Strassmann indicated that nuclear fission not only released a great deal of energy but also produced additional neutrons. These neutrons could continue to induce the fission of other uranium nuclei, forming a self-sustaining chain reaction that generates enormous energy exponentially. This property was subsequently confirmed by many other scientists, including Joliot and colleagues in Paris, as well as Leo Szilard and Fermi in New York.

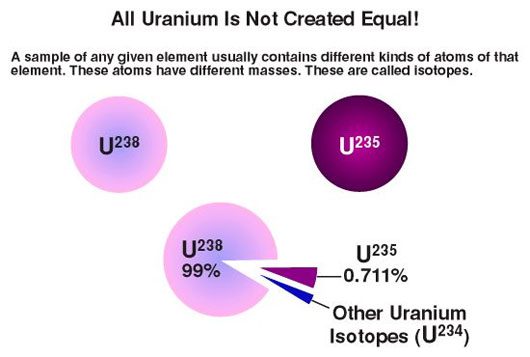

From the earliest studies, Bohr recognized that nuclear fission occurred more readily in the isotope uranium-235 compared to the isotope U-238. He also predicted that the fission process would be more efficient when using slow-moving neutrons rather than high-speed neutrons. This view was later confirmed by Szilard and Fermi, who proposed using a “moderator” to slow down the released neutrons. Bohr and Wheeler subsequently expanded on this idea, leading to the development of the most critical components in nuclear fission systems. Bohr’s research papers were published just two days before the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

Concentration of Uranium Isotopes in Nature

During this period, researchers also discovered that the U-235 isotope only comprises 0.7% of natural uranium, while the remaining 99.3% is the U-238 isotope with similar chemical properties. Given the significant disparity in proportions, separating natural uranium ore to obtain pure U-235 is not a simple task, as it requires entirely different physical methods. Increasing the percentage of U-235 is the concept of “uranium enrichment” that we often hear about.

Another significant study in the development of nuclear energy during this period was the concept of the fission bomb (atomic bomb) proposed by the French physicist Francis Perrin (1901-1992) in 1939. Perrin was the one who suggested the necessary amount of uranium required to produce a self-sustaining nuclear fission system that releases energy. Perrin’s theory was later expanded upon by Rudolf Peierls at the University of Birmingham, and the computational results significantly contributed to the eventual creation of the atomic bomb.

French physicist Francis Perrin (1901-1992), who made significant contributions to the development and construction of the atomic bomb

In Paris, Perrin’s team continued their research and demonstrated that self-sustaining reactions could be carried out in a water environment (to slow down the neutrons). The introduction of external neutrons into the reaction system was also successfully conducted in water. At the same time, the research team proved that various neutron-absorbing materials could be used to control the nuclear reaction process. All of these elements are crucial for the operation of a typical nuclear reactor.

German physicist Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976), one of the most famous physicists of the 20th century with significant contributions to the formation of quantum mechanics

Starting in April 1939, German physicist Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976) and his students began working on a nuclear energy project under the supervision of the Nazi bomb commission. Initially, the project aimed to develop nuclear weapons, but by 1942, it was officially closed with the conclusion that applying nuclear energy for military purposes was impractical.

Nevertheless, the existence of the project spurred the development of the atomic bomb in the UK and the US during wartime. Werner Heisenberg is considered one of the most renowned physicists of the 20th century and made significant contributions to the formation of quantum mechanics. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1932, and notably, the character White in the series Breaking Bad chose the name Heisenberg as a nickname for his underground activities.

The Contributions of Russia in Nuclear Physics

The development of nuclear physics in Russia began to take shape more than a decade before the Bolshevik Revolution. Research was conducted based on radioactive ores found in Central Asia since 1900. In 1909, the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences began conducting large-scale research.

Subsequently, the Russian Revolution of 1917 significantly accelerated nuclear physics research, resulting in the establishment of over 10 research institutes in major cities across Russia in the following years. During the 1920s and early 1930s, Russia implemented numerous new policies encouraging researchers abroad to return to Russia to rapidly enhance expertise in nuclear physics. Prominent scientists responded to the call, including Kirill Sinelnikov, Pyotr Kapitsa, and Vladimir Vernadsky.

From the early 1930s, several research centers specializing in nuclear physics were established and became operational. Kirill Sinelnikov returned from Cambridge in 1931 to establish a nuclear research department at the Ukrainian Institute of Physics and Technology (FTI), founded in 1928 in Kharkov. The famous physicist Abram Ioffe also established a research group at the Leningrad Institute of Physics, which later developed into a nuclear physics institute led by Kurchatov in 1933 with four separate laboratories.

By the end of the decade, numerous magnetic resonance accelerators were installed at the Leningrad nuclear research institute, which was the largest nuclear laboratory in Europe at that time. However, research activities were somewhat interrupted due to Stalin’s purges in 1939. Nonetheless, 1940 witnessed significant advancements in understanding and conducting chain fission reactions.

This led to the establishment of the “Committee on Nuclear Energy Issues” under Kurchatov’s leadership in 1940, which also explored and exploited nuclear raw material deposits in Central Asia. Subsequently, the German invasion of Russia in 1941 turned much of this research into potential military applications.

The Conception of the First Atomic Bombs

During wartime, British scientists faced immense pressure from the government to research nuclear weapons. Two physicists who fled to England, Peierls and Fisch, significantly contributed to the militarization of nuclear energy with their famous three-page record detailing the fundamental concepts of atomic bomb operations.

In the record, the researchers estimated that 5 kg of pure U-235 used to create an atomic bomb could produce an explosion equivalent to several thousand tons of explosives. In this document, the two physicists also outlined the methods for detonating an atomic bomb, how to refine U-235, and the effects of radiation following the explosion. At that time, the proposed method for enriching U-235 from natural ore was thermal separation. This record by the two researchers stimulated the development of atomic bomb construction not only in the UK but also in the US in the subsequent years.

A group of renowned scientists established the MAUD committee in the UK and conducted research under the supervision of universities such as Birmingham, Bristol, Cambridge, Liverpool, and Oxford. The fabrication of uranium gas compounds as well as pure uranium metal was successfully researched at the University of Birmingham and the British Royal Chemical Industry (ICI). Dr. Philip Baxter at ICI successfully synthesized a small amount of Uranium Hexafluoride gas in 1940. Soon after, ICI received an official contract to produce 3 kg of this material for future research activities.

During this period, the University of Cambridge also contributed two other significant studies. The first study demonstrated that chain reactions could be achieved in a mixture of uranium oxide and heavy water to slow down the neutrons, meaning that the output neutrons exceeded the input neutrons. The second equally important study, conducted by Bretscher and Feather, built on earlier work by Halban and Kowarski. When U-235 and U-238 absorb slow neutrons, the fission capability of U-235 is much greater than that of U-238.

At the same time, U-238 is more likely to form a new isotope, U-239, which quickly emits electrons to create a new element with an atomic mass of 239 and an atomic number of 94, with a longer half-life. Thus, Bretscher and Feather established the theory regarding element 94 that it can be easily fissioned by both slow and fast neutrons. This added further chemical advantages over uranium in the extraction from ore with superior properties.

This new discovery was also confirmed by an independent study conducted by American scientists McMillan and Abelson in 1940. The Cambridge research team named the new elements Neptunium with atomic number 93 and Plutonium with atomic number 94, based on the names of the planets Neptune and Pluto. Coincidentally, the research team in the US also proposed similar names for these two new elements in 1941.

The First Model Developed

Rudolf Ernst Peierls (1907-1995), who made significant contributions to the research and development of the atomic bomb

In March 1941, the first reliable confirmation of U-235 fission was achieved. This validated the initial predictions by Peierls and Frisch from 1940 that most collisions between neutrons and U-235 atoms result in fission, regardless of whether the neutrons are slow or fast, both having similar effects. Subsequently, in the verification experiment, researchers clearly recognized that slow neutrons had a significantly better reaction efficiency. This greatly contributed to the advancement of nuclear reactors. However, at this stage, the verification research also strongly stimulated the development of atomic bombs.

Peierls declared that there was no doubt about his hypothesis when it was possible to use pure U-235 to create an atomic bomb. Peierls proposed a model for the atomic bomb with a mass of 8 kg of U-235 designed in a spherical shape. However, he believed that the weight of the bomb could be reduced by using an appropriate neutron-reflecting material. Nonetheless, actual measurements to find the precise parameters still needed to be further researched. Nevertheless, the British government continuously urged the rapid development of an official model.

Report published by MAUD on the achievements in the process of atomic bomb development

The final result was two reports published by MAUD in July 1941 titled “Use of Uranium for Atomic Bombs” and “Use of Uranium as an Energy Source.” The first report indicated that it was entirely feasible to create a 12 kg atomic bomb capable of producing an explosion equivalent to 1,800 tons of TNT and releasing a large amount of radioactive material that could affect the explosion site for an extended period. It was estimated that about $5 million per day and a large skilled labor force would be required to produce 1 kg of U-235 each day. With concerns that the Germans could also create similar weapons, Britain immediately wanted to prioritize collaboration with the United States to quickly manufacture atomic bombs to meet the urgent needs of the war.

The second report from MAUD indicated that it was entirely possible to use heat to provide the initial energy for the fission process in the atomic bomb while being able to supplement a large amount of other radioactive isotopes to replace uranium in the nuclear reaction. The report also indicated that a mixture of heavy water and graphite could be used to control the reaction process. Even ordinary water could be utilized if pure U-235 was used. This was the first model of a uranium reactor still used for harnessing nuclear energy to this day. Simultaneously, MAUD requested Halban and Kowarski to move to the United States to coordinate large-scale heavy water production while in Britain, Bretscher and Feather continued to research the feasibility of using Plutonium as an alternative to U-235 for atomic bombs.

The two reports shaped the successful development of atomic bombs as well as nuclear reactors. These research reports simultaneously positioned Britain as a leader in nuclear energy technology at that time and were referred to as “the most effective method ever existing for harnessing nuclear energy.” Of course, the United States valued the achievements of the British scientists, and at that time, the research objectives of the National Academy of Sciences and many researchers shifted to pursuing nuclear energy goals.

Subsequently, the urgent need for the U.S. to quickly possess nuclear weapons became more pressing after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and the U.S. officially entered the war in July 1941 to turn the tide of the conflict. All of America’s resources were dedicated to the development of atomic bombs.

The Manhattan Project

Americans worked day and night on research and development with all available resources, and as a result, they quickly surpassed the British. Research efforts continued to expand and were frequently exchanged between the two nations. In 1942, several key British scientists visited the United States and were granted access to all information regarding U.S. research efforts.

At that time, the U.S. was conducting parallel research on three different nuclear reaction models: Professor Lawrence from the University of California proposed using electromagnetic separation techniques, E.V. Murphree suggested a centrifuge method with contributions from Professor Beams, and finally, the gas diffusion method was researched by Professor Urey from Columbia University. Simultaneously, the responsibility for researching and developing plutonium fission reactors was given to Arthur Compton at the University of Chicago. British scientists were particularly interested in the gas diffusion method.

Churchill signs with President Roosevelt at the Quebec Conference in 1943

In June 1942, the U.S. military undertook the development, design modeling, procurement of materials, and selection of a network of factories to pilot all four methods proposed by scientists to produce heavy water on a large scale (as no research had yet proven the feasibility and superiority of any one method). This caused significant obstacles for British and Canadian scientists who were jointly researching some aspects of heavy water production. Subsequently, British Prime Minister Churchill proposed information about the cost of building a heavy water plant and a nuclear reactor in Britain.

After several months of negotiations, an agreement was signed by Churchill with President Roosevelt in Quebec in August 1943. According to this agreement, the British would hand over all their nuclear research reports to the U.S. in exchange for receiving a copy of the progress report on nuclear weapons research from General Groves. Subsequent reports indicated that the U.S. spent a staggering $1 billion solely on atomic bombs without any other applications.

First nuclear bomb test in the Manhattan Project

In December 1942, Fermi conducted an experiment using graphite to control the nuclear reaction process at the University of Chicago. The success of the experiment marked the first time that a nuclear chain reaction could be controlled.

At the same time, a plutonium fission reactor was constructed at Argonne, followed by others at Oak Ridge and Hanford, along with another plant built that included a plutonium re-extraction cycle. Additionally, four heavy water production plants were established, one in Canada and three others in the U.S. The director of the Manhattan Project, physicist Robert Oppenheimer, led a research team at the secret laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to design and manufacture both U-235 and Pu-239 bombs. As a result of all these research efforts, along with contributions from British researchers, a large amount of high-purity U-235 and Pu-239 was successfully enriched. Most of the uranium ore originated from the Congo.

The first nuclear device was successfully tested at Alamagordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. The device utilized plutonium produced in a nuclear reactor. The team decided that there was no need to test the U-235 bomb model due to its simpler operating principle. The first atomic bomb, containing U-235, was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The second bomb, containing Pu-239, was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9 of the same year. On that same day, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and finally, on August 10, 1945, the Japanese government surrendered.

The Soviet Bomb

Initially, Stalin did not pay much attention to the development of nuclear weapons or atomic bombs until receiving intelligence about the research activities of Germany, Britain, and the United States. In 1942, with the advice of military leaders, Stalin eventually accepted the development of nuclear weapons, estimating that it would not take long and would not require many resources. Igor Kurchatov, a young and previously unknown researcher, was chosen to pursue the project in 1943 and became the director of Laboratory No. 2 established on the outskirts of Moscow. Later, the laboratory was renamed the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy, with the overall responsibility for researching the fabrication of atomic bombs.

Research was conducted in three main areas: controlling the chain reaction, finding methods for isotope separation, and designing bombs from enriched uranium and plutonium. Initial efforts successfully created a chain reaction using graphite rods and heavy water to regulate the reaction. Isotope separation methods tested included thermal diffusion, gas diffusion, and electromagnetic separation.

Igor Kurchatov, a physicist who made significant contributions to the development of the atomic bomb in Russia

After the Nazis surrendered in May 1945, German scientists were recruited for the atomic bomb program to find effective methods for isotope separation in uranium enrichment. In addition to the three methods previously researched, scientists proposed a centrifuge method for uranium enrichment. However, the successful test of the atomic bomb by the United States in July 1945 influenced the Soviet efforts significantly. At that time, Kurchatov was making optimistic progress in the development of uranium and plutonium bombs. He began designing an industrial-scale plutonium production reactor while other scientists focused on separating U-235 isotopes based on advancements in gas diffusion methods.

Building on the successes of uranium enrichment technology from 1945, the Soviet Union decided to construct the first gas diffusion enrichment plants in Verkh-Neyvinsk, located 50 km from Yekaterinburg. Subsequently, the nuclear weapons design bureau and a series of plants were established with the support of many Russian and German scientists. In April 1946, the bomb design work was transferred to Design Bureau 11, located 400 km from Moscow. Many experts were tasked with participating in the program, including metallurgist Yefim Slavsky, who was assigned to immediately produce pure graphite to use as control rods in nuclear reactors. The first control rods were officially used in December 1946 at laboratories 2 and 3 in Moscow (now the Institute of Experimental Physics).

Based on intelligence information and studies of the bomb at Nagasaki combined with earlier research, a test bomb model was finally established in August 1947 at Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, and was ready for a test explosion. However, it was two years later that the first bomb, named RSD-1, was officially tested there. Nevertheless, as early as August 1949, a group of leading scientists, including Igor Tamm and Andrei Sakharov, began research aimed at developing the next generation: the hydrogen bomb.

The Revival of Nuclear Reactors for Peaceful Purposes

After World War II, earlier research on nuclear weapons began to be reconsidered for peaceful purposes. Although nuclear weapons remained a dividing factor between the two sides of the “Iron Curtain” in Europe, significant resources were still invested to develop nuclear energy for steam and electricity. During the arms race, both Western countries and the Soviet Union purchased numerous technologies surrounding nuclear energy, and during their research, scientists discovered the potential of harnessing nuclear energy directly to generate electricity. This opened up vast possibilities for nuclear energy, from supplying national electricity grids to powering submarines.

In 1953, U.S. President Eisenhower proposed the “Atoms for Peace” program, calling for nuclear research aimed at electricity generation while establishing the development of the civilian nuclear power industry in the United States.

In the Soviet Union, various research initiatives were also undertaken at power plants across the country to improve nuclear reaction processes and develop new applications. In May 1946, the Institute of Electrical Engineering was established with the goal of developing nuclear power technology. Nuclear power plants were founded based on earlier principles of using graphite and heavy water to control the reaction process. This basic model was initially used for military purposes during wartime to enrich plutonium, including the infamous Chernobyl nuclear plant. The AM-1 safe nuclear reactor achieved an electricity output of 30 MWt and continued to generate electricity until 1959. After that, until 2000, it served as a research center and produced radioactive isotopes in Russia.

Commercialization of Nuclear Energy

Entrance to the Yankee Rowe commercial nuclear reactor

In the United States, Westinghouse designed the first commercial pressurized nuclear reactor with a capacity of 250 MWe. The plant, named Yankee Rowe, began construction in 1960 and officially went into operation in 1992. At the same time, a boiling water reactor (BWR) with a 250 MWe capacity was developed by Argonne National Laboratory. The first plant to implement BWR technology, named Dresden-1, was officially designed and built by General Electric in 1960. By the end of the 1960s, orders for both PWR and BWR models increased, with capacities rising to 1000 MWe. From the 1970s to 2002, the nuclear energy industry faced several downturns and stagnations. A few reactors were ordered, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that this number increased by over 30%, with utilization efficiency also rising to 60%.