Under record-breaking heat, the lives of residents in Jacobabad (Pakistan) are in crisis, especially for vulnerable groups like young children and pregnant women.

Pregnant woman Sonari struggles to move under the scorching sun in fields scattered with yellow melons in Jacobabad, which became the hottest city in the world in May.

Waderi, Sonari’s 17-year-old neighbor, gave birth a few weeks ago. She is returning to work in conditions where temperatures can exceed 50 degrees Celsius. The young mother has to place her newborn in the nearby shade to feed him when he cries, according to Reuters.

“We feel stressed as the heat comes while we are pregnant,” Sonari, in her twenties, stated.

According to an analysis of 70 studies conducted since the mid-1990s, pregnant women exposed to high temperatures for extended periods face a higher risk of complications.

According to a meta-analysis by the Global Climate and Health Education Association at Columbia University, published in the British Medical Journal in September 2020, for every 1 degree Celsius increase, the rate of stillbirths and preterm births rises by about 5%.

Sonari exhausted from working outdoors in the heat while pregnant.

The rising temperature in poorer countries affected by extreme weather due to climate change particularly impacts women. Many have little choice but to work during pregnancy and immediately after giving birth.

Moreover, women in conservative societies like Pakistan often cook for their families over hot stoves or ovens in cramped rooms without ventilation or cooling systems.

Extreme Heat

The South Asian region has faced unusual heatwaves in recent months. According to scientists at the international research collaboration World Weather Attribution, the recent severe heatwaves in India and Pakistan are 30 times more likely to occur due to climate change.

About 200,000 residents of Jacobabad are well aware that they live in one of the hottest cities in the world.

“If we go to hell, we’ll take a blanket with us,” is a joke many share with one another.

Sonari and Waderi work alongside about a dozen other women, some of whom are pregnant, in the melon fields located about 10 kilometers from the center of Jacobabad.

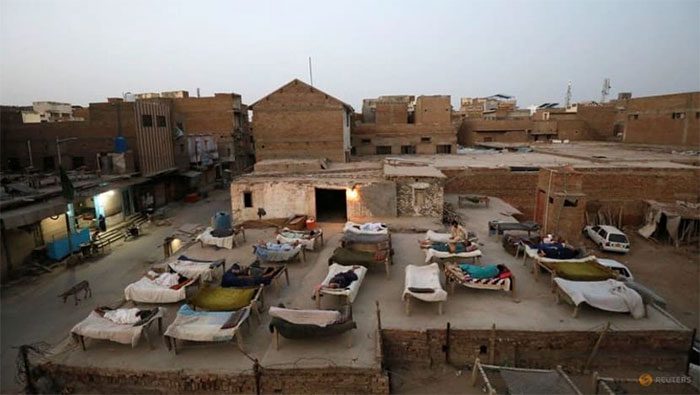

Record heat making it difficult for many residents, especially women in Jacobabad.

They start working at 6 AM, take a short break at noon to manage household chores and cooking, then return to work until sunset. Many face leg pain, fainting spells, and discomfort while breastfeeding.

“It feels like no one sees them, no one cares about them,” remarked relief worker Liza Khan, referring to the plight of many women in Jacobabad and the broader Sindh region.

Khan’s phone rings incessantly as she drives to one of three heatstroke response centers she helped establish in recent weeks. This is also part of her work with a nonprofit organization called the Community Development Organization.

With a degree in finance, Khan once lived in cooler cities across Pakistan but chose to return to her hometown to support women in the area.

“Right now, I work 24/7,” the 22-year-old said, adding that her organization has found that the impacts of extreme heat are increasingly intertwined with other social and health issues affecting women.

Challenges

On May 14, daytime temperatures in Jacobabad reached 51 degrees Celsius, making it the hottest city in the world at that time, coinciding with tragedies caused by the heat.

While preparing lunch for visiting relatives, young mother Nazia, who has five children, collapsed in a kitchen without a fan or air conditioning. She was taken to a nearby hospital but could not survive; her death was attributed to heat stroke.

Local health officials did not respond to requests for comments on the number of heat-related deaths in Jacobabad in recent years or specifically regarding Nazia’s case.

High temperatures making Jacobabad one of the hottest cities in the world.

Poverty and frequent power outages prevent many residents from buying or using air conditioning, and sometimes even fans to cool off.

Many experts suggest using clean energy stoves instead of cooking over open flames, providing medical and social services for women in the early morning or evening when it’s cooler, and replacing tin roofs with cooler, white materials to reflect solar radiation.

Pakistan’s Climate Change Minister Sherry Rehman noted that women are likely to continue bearing the brunt of rising temperatures and suggested that future climate policies need to address the specific needs of women.

“Climate change poses a significant threat to the lives of vulnerable women in rural areas and urban slums. Women on the margins in Pakistan will be the most affected.”

Prayer

In a neighborhood of the city, a donkey cart driver delivers 20-liter water bottles sourced from one of the dozens of private pumps around the city.

Most residents in Jacobabad rely on such water deliveries, which can consume 1/8 to 1/5 of a household’s meager income. However, water remains frequently insufficient.

For young mother Razia, the cries of Tamanna, her 6-month-old baby in the afternoon heat, are enough to convince her to pour a bit of precious water over her child. Afterwards, she places Tamanna in front of a fan, and the child quickly calms down, playing with her mother’s scarf.

Pregnant women and children facing numerous health issues due to the heat.

Local officials stated that the water shortage is partly due to electricity cuts, meaning water cannot be filtered and pumped through the pipes across the city.

Rubina, Razia’s neighbor, often has to fry onions and okra over an open flame. She frequently feels dizzy from the heat and tries to pour water over herself whenever she cooks to avoid fainting.

However, she does not always have enough water to do so.

“We often run out of water before it’s time to buy more and have to wait. On hot days without water and electricity, we wake up, and the only thing we do is pray,” Rubina shared.