The scientific community has yet to reach a consensus, as the strange Mpemba effect continues to evade the curious eyes of researchers.

At first glance, the question seems absurdly simple: “If you place two cups of water, one hot and one cold, in the freezer, which one will freeze first?”

Common sense suggests that the colder water will freeze faster, yet philosophers like Aristotle and René Descartes have observed and recorded the opposite. In modern times, plumbers have noted instances of hot water pipes bursting in cold weather, while cold water pipes function normally.

Although this phenomenon can be observed, subsequent experiments have failed to make hot water freeze faster than cold water. Highly precise experiments are affected by countless variables, making it difficult for researchers to determine the factors influencing the results.

In recent years, researchers have discovered that the Mpemba effect occurs in other compounds, including crystalline polymers, substances known as clathrate hydrates, and manganese minerals cooling in a magnetic field. These new research directions provide scientists with additional data about a complex system that falls outside the conventional rules of thermodynamic equilibrium.

Some physicists have attempted to model the unusual principles described above, predicting that the Mpemba effect would appear in various materials; furthermore, the reverse effect—where cold substances warm up faster than warmer ones—also occurs. Recent experiments have begun to confirm these assertions.

However, the Mpemba effect occurring in water—the most familiar and abundant substance used in experiments—continues to elude expert scrutiny.

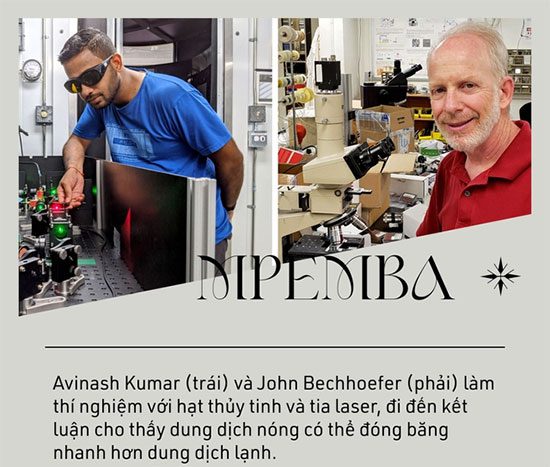

“A cup of water in the freezer seems simple,” physicist John Bechhoefer states, “but in reality, it’s not easy at all if you really pay attention to the research.” Working at Simon Fraser University, Bechhoefer is currently the most experienced individual in researching the Mpemba effect.

When Reality Defies Common Sense

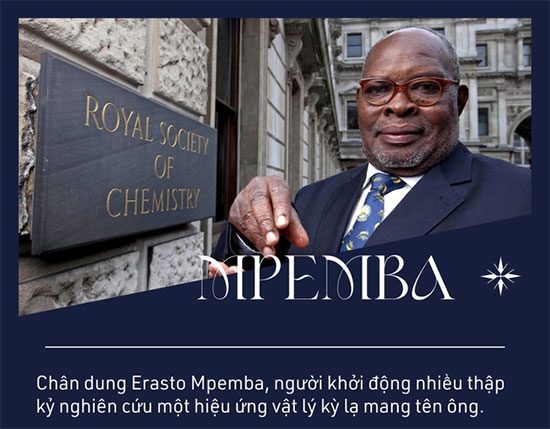

“My name is Erasto B. Mpemba, and I’m going to tell you about my discovery, which came about from misusing a refrigerator.” This was the premise of a scientific report published in 1969 in the journal Physics Education, where student Mpemba described his efforts to make ice cream while attending Magamba High School in Tanzania.

With limited space in the freezer, Mpemba had to quickly place his ice cream mixture inside. Mpemba skipped the cooling phase of the milk and sugar mixture, placing the tray directly into the freezer without allowing it to reach room temperature. An hour and a half later, his milk and sugar mixture had frozen into ice cream, while his classmates’ mixtures remained thick and soupy. When he asked his physics teacher about it, Mpemba received the response: “You’re mistaken. That can’t happen.”

Mpemba repeated this question when physicist Osborne visited the school. “If you take two cups of water with equal volumes into the freezer, one at 35 degrees Celsius and one at 100 degrees Celsius, the cup of hot water at 100 degrees Celsius will freeze first. Why is that?” The laughter of Mpemba’s friends and the teacher could not dissuade Osborne’s curiosity. After experimenting himself, the physicist from England discovered the effect described by Mpemba.

However, he concluded that the experiment was still rudimentary and required more in-depth tests to verify the phenomenon.

Decades passed, and scientists proposed various hypotheses to explain the Mpemba effect. Noticing that water is a peculiar substance—solid ice is less dense than liquid water, and the two phases can coexist at certain temperatures—some experts suggest that raising the temperature may weaken the fragile hydrogen bonding network, increasing the disorder in the structure and reducing the energy needed for freezing.

Another, simpler explanation points out that hot water evaporates faster than cold water, resulting in reduced volume and, therefore, shorter freezing time. Cold water also contains a higher amount of dissolved gases, leading to a lower freezing point.

Some experts believe that the outer ice layer acts as an insulator, preventing heat loss from the cup, while the hot cup melts the outer ice layer, causing the hot water to cool more rapidly.

All these explanations agree on the assertion that hot water freezes faster than cold water. Yet, the scientific community remains divided.

In 2016, physicist Henry Burridge from the Royal College of London and mathematician Paul Linden from Cambridge conducted experiments to demonstrate how sensitive the effect is to specific measurements. They observed that hot water formed ice crystals earlier; however, it took longer to freeze completely. Both phenomena are difficult to measure, so Burridge and Linden measured the time it took for water to reach 0 degrees Celsius.

They found that the measurements depended on the position of the thermometer. When two cups of water were placed at the same height, the Mpemba effect did not occur. Just a one-centimeter difference in height resulted in a “false” Mpemba effect. Reviewing related literature, Burridge and Linden found that the Mpemba effect only appeared in the initial research reports by Osborne and Mpemba.

The physicist and mathematician’s findings “demonstrate how sensitive experiments can be, even without recording the freezing process.”

Strange Shortcuts

A significant number of scientists believe in the existence of the Mpemba effect, asserting that at least it occurs under certain conditions. From the 4th century BC, the great philosopher Aristotle observed: “When people want to cool water quickly, many place it under the sun”; it seems that this strange effect existed even before thermometers were invented. Mpemba as a student also witnessed a similar phenomenon when comparing the freezing speeds of his ice cream to that of his classmates.

Nevertheless, the discoveries of Burridge and Linden indicate that the main reason the Mpemba effect, whether real or not, is difficult to observe in experiments lies in the rapidly changing temperature in a cup of water that is cooling, which is not in equilibrium. Meanwhile, physicists do not yet fully understand the systems of matter outside of equilibrium.

When equilibrium occurs, any solution in a bottle can be described by an equation involving three variables: temperature, volume, and number of molecules. Placing the bottle in the freezer causes the values to change uncontrollably, leading to inconsistent measurement results. The outer particles become trapped in the cold while the material deep inside the bottle retains its warmth. Temperature and pressure measurements also fluctuate unpredictably.

When Assistant Professor Lu Zhiyue learned about the Mpemba effect while still in school, he sneaked into an oil refinery in Shandong province where his mother worked to recreate the experiment. Measuring the time it took for the temperature of freezing water to change, he was able to lower the water below 0 degrees Celsius without it freezing (a process known as “supercooling”).

Later, as he delved deeper into thermodynamics in a non-equilibrium system, he tried the cooling method used previously to recreate the Mpemba effect. He posed the question: “Is there any thermodynamic law that prevents the following phenomena from occurring: a [substance starting the transition] far from the equilibrium point reaching equilibrium faster than a [substance] closer to equilibrium?”

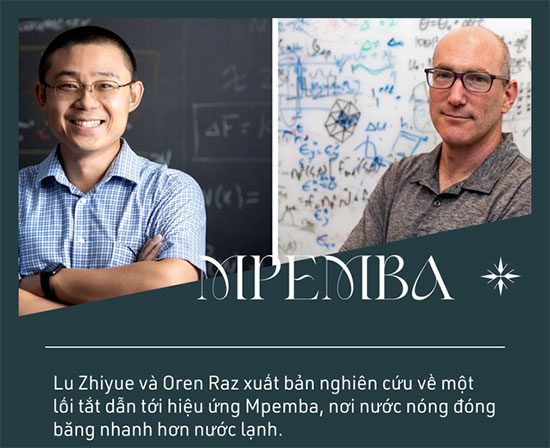

When he met Oren Raz, an expert in non-equilibrium statistical mechanics at the Weizmann Institute, Zhiyue had the opportunity to develop a model to study the Mpemba effect in various materials beyond water. In 2017, they became co-authors on a scientific paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describing the random dynamics of particles and demonstrating that, in principle, certain non-equilibrium conditions could generate the Mpemba effect and its reverse effect.

The abstract findings suggest that the components of a hot matter system (i.e., containing a lot of energy) may produce more feasible mechanisms, one of which allows cold matter to travel through an unusual shortcut, enabling the hot system to surpass the cold system in the race to the freezing point.

“We all naively think that temperature changes monotonically. You start at a high temperature, then move to average, and then go low,” researcher Oren Raz states. But in a system that is no longer in equilibrium, “the assertion that the system possesses a certain temperature is no longer true,” and “therefore, shortcuts can emerge.”

A curious scientific report has captured the attention of many researchers, including a group of Spanish scientists experimenting with a colloidal solution—a combination of hard particles that can flow like a liquid, such as sand or seed grains. Through a simulation model, the research team found that the colloidal solution can also produce effects similar to those described by Mpemba years ago.

This led probability physicist Marija Vucelja from the University of Virginia to question the frequency of the Mpemba effect occurring in nature. “Is this a drop in the ocean, or can we leverage it to [create] optimal heating or cooling rules?” she wondered. In 2019, she, along with Oren Raz and two other co-authors, discovered that the Mpemba effect could occur in a chaotic mixture of substances unlike water, such as glass. This finding opened the possibility of the Mpemba effect appearing in many other materials.

To delve deeper, researchers Lu Zhiyue and Oren Raz sought out physicist Bechhoefer, an individual with extensive experience in real-world experimentation.

Exploring New Boundaries

The experiment proposed by Bechhoefer and colleague Avinash Kumar encompasses advanced concepts but provides a stark perspective on a group of particles influenced by various forces. A microscopic glass particle represents a material particle placed in an “energy landscape” created by a laser.

The deepest well in this landscape is a point of high stability, while the shallower wells describe a “metastable” state—where a particle can exist but can still fall into a more stable region. The scientists submerged the entire energy landscape in water, using optical tweezers to position the glass particle at 1,000 different locations; the experiment would yield similar results with a system comprising 1,000 material particles.

Experimentation

Physicists created an artificial energy landscape, where the existence of a particle would require different amounts of energy.

They released a glass particle into the model at various positions and energy levels (higher levels correspond to hotter particles, while lower levels correspond to colder particles).

Each particle would move toward a state of equilibrium, oscillating between the two wells of the given energy landscape.

Results

The hotter glass particle reached equilibrium first.

A high-energy context allows the glass particle to be placed anywhere, as a hotter system is energy-rich, enabling more possibilities to occur. In a system that is merely warm, the placement of the glass particle will be closer to the well. During the cooling process, the glass particle will settle in one of the wells, then oscillate between the two regions (also influenced by water molecules).

The cooling process concludes when the glass particle remains in one well for a certain duration, for instance, spending 20% of the time in the metastable well and 80% in the stable well. This ratio depends on the water temperature and the size of the wells.

Under certain conditions, a hot system takes longer to reach equilibrium than a warm system; meaning a cup of hot water will freeze slower than a cup of cold water. However, in some cases, the Mpemba effect occurs. Most notably, there are conditions under which the hot system cools down faster than expected; researchers have named this state the “strong Mpemba effect.” The scientific report was published in the journal Nature in 2020.

“The results are clear,” said Raúl Rica Alarcón from the University of Granada in Spain, who is also researching the Mpemba effect. “They successfully described a system starting far from equilibrium but reaching it faster than systems that are closer.”

In other words, the report confirms the existence of the Mpemba effect while showing that under certain conditions, the effect can occur more strongly.

The results have not yet convinced the entire research community that the Mpemba effect can appear in any system. “I always read through these experiments, and I’m not impressed with how they are presented,” researcher Burridge stated. “I still haven’t seen a reasonable physical explanation, and I feel the question remains unresolved: does a phenomenon similar to the Mpemba effect exist in a beneficial way?”

It seems Bechhoefer’s experiment indicates that the Mpemba effect may appear in systems containing metastable states. However, researchers are unclear whether this is the only mechanism causing the Mpemba effect, and the way material particles undergo the process of non-equilibrium heating and cooling remains shrouded in discovery.

With nothing changing, research related to the Mpemba effect has provided physicists with a foothold in the often flawed non-equilibrium system. “The question of how [material particles] move to equilibrium is an important one, and frankly, we still don’t have a reasonable theory to explain it,” Mr. Raz noted. Identifying which systems might react in a rather peculiar way “will provide a clearer view of how a system progresses to equilibrium.”

After igniting a debate that has lasted for decades, Mpemba did not pursue physics. He returned to nature through wildlife management, later becoming an official in the Ministry of Tourism and Natural Resources of Tanzania. According to Christine Osborne, the widow of researcher Denis Osborne, Mpemba passed away in 2022. He left behind one of science’s greatest mysteries in the form of a peculiar effect bearing his name.