Currently, all we know about the brain is that it is a mass of nervous tissue situated between our ears. This mass contains our understanding of the world, the history of humanity, and all the skills we have learned — from riding a bike to persuading a loved one to let go of their romantic attachment. Memory makes each person a unique individual and creates a continuous flow for our lives. Understanding how memories are stored in the brain is a crucial step in the exploration of human identity.

|

|

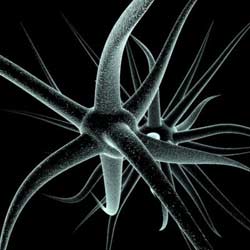

Neurons in the brain (Photo: transformedpuppet) |

Neuroscientists have made significant strides in identifying key areas of the brain and potential molecular mechanisms. However, many important questions remain unanswered, and there is still a vast chasm separating molecular-level research from the operations of the entire brain.

In 1957, the publication of the neurological case of patient H.M. ushered in a new era in memory research. At the age of 27, H.M. underwent surgery to remove large portions of his temporal lobes in an effort to treat his chronic epilepsy. The surgery was successful, but afterward, H.M. could not remember what had happened or the people he encountered. This case demonstrated that the medial temporal lobes (MTL), which contain the hippocampus, play a crucial role in memory formation. H.M.’s case also provided more compelling evidence that memory is not a rigid block. For three consecutive days, researchers assigned H.M. three identical drawing tasks designed to be “deceptive.” The result was that H.M.’s performance improved rapidly and noticeably after each task, even though he had no recollection of the previous day’s exercise. H.M.’s case proved that remembering “how” is different from remembering “what.”

From experiments on animals and advancements in describing the human brain, scientists today have experimental insights into various forms of memory corresponding to specific brain regions. However, scientists have yet to fill in the gaps in understanding that have persisted for a long time.

|

|

The great Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Photo: bio) |

Although the medial temporal lobes have been proven essential for “declarative memory” — the recollection of actual events — there are still unclear aspects within this region. How different components interact during the encoding and retrieval of memories remains a mystery. Moreover, the medial temporal lobes are not the final storage site for “declarative memories.” These memories seem to be organized in the cortex for long-term storage, yet how this occurs and how memories are represented in the cortex is still not clear.

More than a century ago, the great Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal proposed that the formation of memories requires a close connection between neurons. At that time, it was believed that neurons were not generated in the mature brain; thus, Ramón y Cajal made a reasonable assumption that some changes must occur among the existing neurons. Only recently have scientists begun to gather clues to explain how this phenomenon might occur.

However, since the 1970s, research on distinct parts of the nervous system has identified the “host” among the molecules involved in memory formation. Many different species have shown that numerous similar molecules are related to both declarative and non-declarative memory. This evidence suggests that the molecular mechanisms of memory are conserved across various organisms. Moreover, these studies highlight that short-term memory (lasting minutes) involves chemical changes that enhance the strength of existing synaptic connections between neurons, while long-term memory (lasting days and weeks) requires protein synthesis and possibly the formation of new synapses.

|

|

Neuron (Photo: turbosquid) |

The current challenge is how to apply these findings to the entire brain. A promising bridge is the process known as Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) — a form of synaptic enhancement that has been extensively studied in the hippocampus of rodents. LTP is believed by many to be the physiological basis of memory. It would be a major breakthrough if someone could conclusively illustrate that LTP is indeed foundational for memory formation in vivo.

Meanwhile, questions continue to arise. Recent studies have discovered that the neural patterns recorded when an animal learns a new skill are repeated while the animal is sleeping. Does this play a role in consolidating memories? Other research indicates that our memories may not be as reliable as we often assume. Why is memory not so enduring? One suggestion may come from recent studies that revive the controversial view that memories are highly susceptible to distortion whenever they are retrieved. Finally, in the 1990s, there was strong support for the theory of “no new neurons.” This theory posited that, among all areas, the hippocampus is the nursery for neurons throughout life. How newly generated cells participate in learning and memory remains unanswered.

Dương Văn Cường