There are countless stars visible in the night sky, but over the centuries, astronomers have devised unique ways to identify them.

Surely, some of us have spent an entire night gazing up at the sky, marveling at the breathtaking sights of stars, planets, constellations, and even galaxies. Those with years of stargazing experience can even recognize some of the brighter stars.

In that mysterious night sky, there are innumerable stars. Even without using a telescope or other optical aids, we can still see hundreds of stars on a clear night, away from the city’s lights. So, have you ever wondered how all those stars are named and identified?

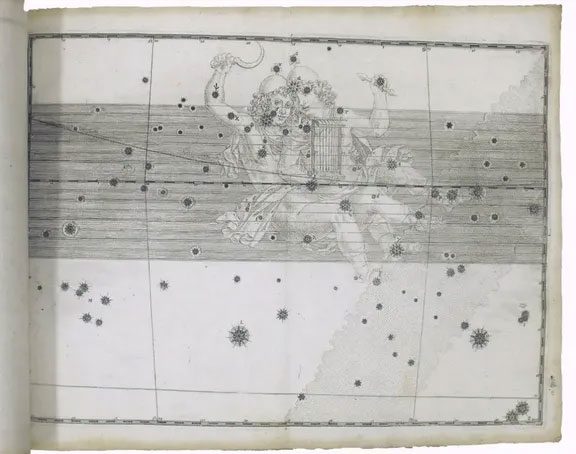

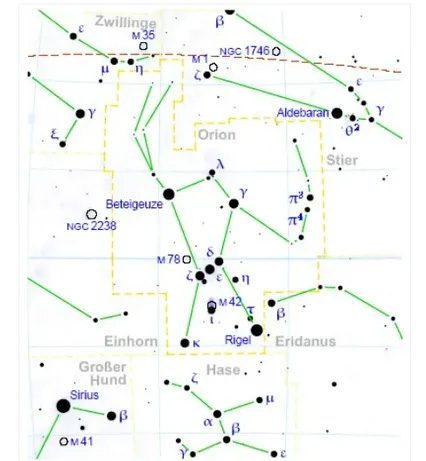

Image of the Gemini constellation from Bayer’s star atlas

To answer this question, we first need to go through a brief historical overview of how humans have named stars over the centuries. The brightest and most prominent stars in the night sky were often named in the past and continue to be used today. However, modern professional astronomy involves assigning identifiers to stars using letters and numbers, which are used in all official catalogs.

For instance, the brightest star in the Lyra constellation is named Vega, but it also has designations such as Alpha Lyrae (Bayer designation), 3 Lyrae (Flamsteed designation), HR 7001 (from the Yale Bright Star Catalog), and other names in various catalogs.

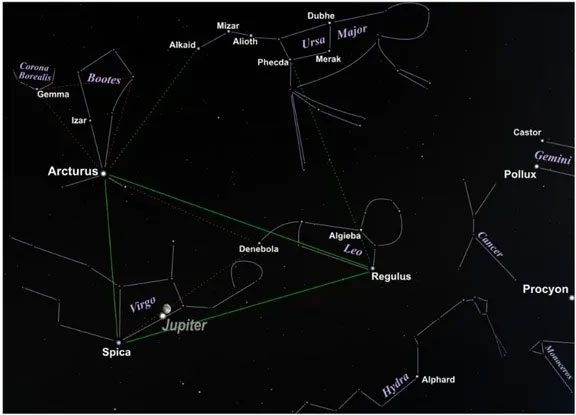

We will explore the names assigned to stars, which are both proper names and of ancient, recent, or organizational origins under the International Astronomical Union (IAU). The oldest proper names mostly originate from ancient Greek. Some typical examples include Sirius – the Dog Star, Procyon (also the name of a genus of animals), and Arcturus – following the Ursa Major constellation (the Great Bear).

Diagram of the famous Spring Triangle. Arcturus follows Ursa Major as it moves across the sky.

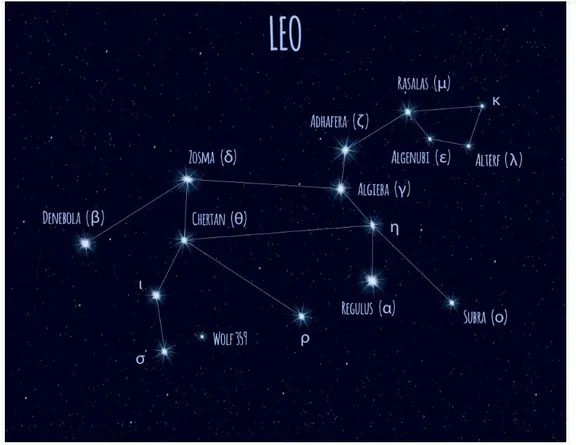

However, most proper names of stars have Arabic origins, as they were labeled by Arab astronomers during the Middle Ages. These names often come with a wealth of legends and origins based on the stars’ positions within their constellations. For example, the name Deneb means “tail,” Aldebaran means “the follower,” and Fomalhaut means “the mouth of the whale.”

This chart contains the proper names of prominent stars in the Leo constellation. The Greek letters in parentheses are the Bayer designations of the respective stars.

Currently, naming a star with a proper name is not highly regarded. It not only involves considerable paperwork but has also led to instances where two or more stars received the same name, such as ‘Deneb’ in the Cygnus constellation, ‘Denebola’ in the Leo constellation, and ‘Deneb Kaitos’ in the Cetus constellation. In some cases, when Arabic names are translated into other languages, such as Latin, the meanings of the star names can sometimes be lost.

In 1600, Johannes Bayer published his star naming catalog. In it, he used lowercase Greek letters for stars in order of decreasing brightness within the same constellation. Thus, the most convincing interpretation is that the brightest star in a constellation would be designated as ‘Alpha’, the second brightest as ‘Beta’, and so on. The Greek letter is followed by the Latin name of the constellation. For example, Sirius, the brightest star in the Canis Major constellation, is designated as “Alpha Canis Majoris” with the Latin genus “Canis Majoris,” which simply means “belonging to Canis Major.”

The Orion constellation and other neighboring constellations show the Bayer designations of its constituent stars.

However, Bayer did not always adhere to his own brightness scheme. If we look at the Ursa Major constellation, he simply assigned Greek letters to the stars from west to east, where the first and second brightest stars are respectively called “Beta Geminorum” and “Alpha Geminorum.”

Another fact is that there are only 24 Greek letters. Bayer attempted to address this issue by using lowercase Latin letters from a to z (numbered from the 25th to the 50th stars) and then using uppercase Latin letters A-Z (assigned to the 51st to 76th stars). However, these schemes are not widely used.

Two hundred years after Bayer first introduced his system, John Flamsteed introduced his numerical classification system. In this scheme, stars are numbered from west to east within each constellation. Thus, the westernmost star in the Taurus constellation is named 1 Tauri, the second westernmost star is named 2 Tauri, and so on. Note that the Latin name of the constellation is added after the Flamsteed number. In total, more than 2,600 stars have received Flamsteed numbers.

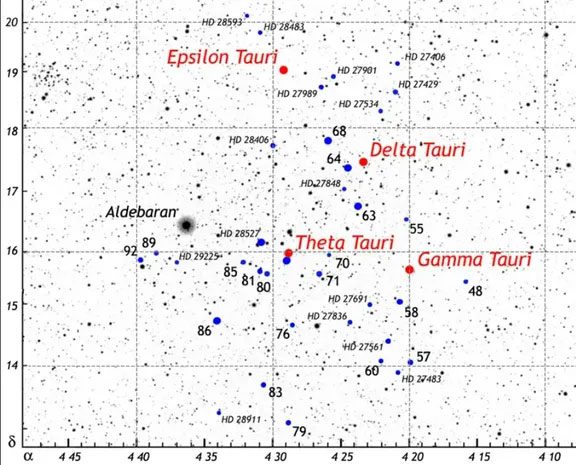

Image of the core stars in the Hyades cluster.

Both Bayer and Flamsteed names include the prominent and bright stars in a constellation. As fainter and less prominent stars have been discovered over time, there was a need to establish a new system to identify these stars. Therefore, new catalogs based on the star’s position in the sky were created, using a coordinate system similar to Earth’s latitudes, without regard to the parent constellation.

One of the most commonly used catalogs in astronomy is the Yale Bright Star Catalog. The stars in this catalog are designated as ‘HR’ or ‘BS,’ followed by a four-digit number. Here, ‘HR’ refers to ‘Harvard Revised,’ as the cataloging was first done by Harvard before Yale began publishing it. This catalog includes approximately 9,110 stars, with examples of this classification including HR 2326 (Proper Name: Canopus) and HR 7001 (Proper Name: Vega).

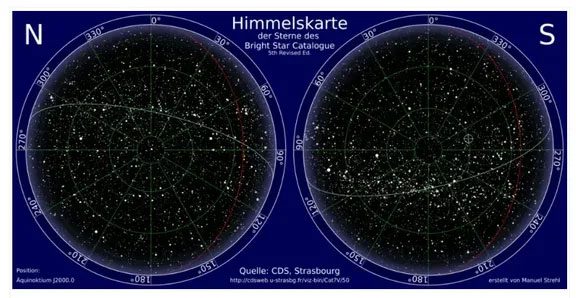

Sky map with star positions from the Bright Star Catalog

Another catalog commonly used in astronomy is the Henry Draper Catalog (HD). This catalog also uses the positions of stars in the night sky and lists over 225,000 stars, with names prefixed by “HD” followed by a six-digit number. It also contains information about the spectral classes of the stars – an indication of the type of radiation emitted by the star. The HD catalog includes both bright and faint stars.

A well-known catalog for identifying faint stars is the Durchmusterung. This list includes stars fainter than 50 times the dimmest stars visible to the naked eye, which are observable from surveys such as the Bonn Survey (‘Bonner Durchmusterung’ in German) and the Cordoba Survey (‘Cordoba Durchmusterung’ in German).

Other commonly used catalogs include the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Catalog (SAO), the Positions and Proper Motion Catalog (PPM), and the Guide Star Catalog for the Hubble Space Telescope (GSC). An example of classification is the second brightest star in the Orion constellation, which has the proper name ‘Betelgeuse’ and the following designations: Alpha Orionis (Bayer designation), 58 Orionis (Flamsteed designation), HR2061 (Yale Bright Star Catalog), HD39801 (Henry Draper Catalog), BD + 7 1055 (Bonner Durchmusterung Catalog), and SAO113271 (Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Catalog).

To date, catalogs related to individual stars usually have fixed magnitudes. However, there are binary stars or star clusters – two or more stars that appear very close together and may or may not be gravitationally linked – as well as variable stars over time. In this case, one of the commonly used methods to label them includes assigning uppercase Latin letters in the order of their discovery or decreasing brightness. Here, the primary star will have the letter ‘A’ after its proper name or designation, followed by the appropriate Latin letter for the companion stars. For example, the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, has its primary star designated as Sirius A and the companion star designated as Sirius B.

Binary star system with the primary star labeled as Sirius A and the companion star as Sirius B

For variable stars, the first labeling system was proposed by Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander, who used the remaining letters from the Bayer designation scheme. Bayer had gone as far as the classification ‘Q’, meaning the first variable star discovered in a constellation would be labeled ‘R’, followed by ‘S’, and so on. After exhausting ‘Z’, double-letter designations such as ‘RR’, ‘RS’, and so forth up to ‘ZZ’ would be employed. As more variable stars were discovered, astronomers began labeling them from ‘AA’, ‘AB’, all the way to ‘QZ’. An example of this scheme is R Cygni, as it was the first variable star discovered in the constellation Cygnus.

Subsequently, astronomers utilized the designation V followed by a three-digit number. For example, V335 Tauri in the constellation Taurus is a variable star by this nomenclature.

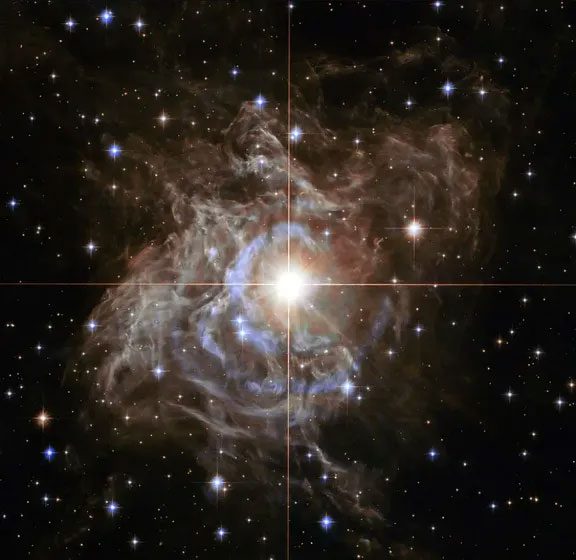

The variable star labeled as RS Puppis, captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.

Naming and cataloging stars is a crucial aspect of modern astronomy. With more surveys leading to a greater number of stars, naming them simplifies the study of their properties and characteristics. In some cases, catalogs also provide additional information about these stars.

Humanity has made significant strides in studying stars and star systems, with the naming of stars playing a fundamental role in our understanding and appreciation of the wonders of the universe.