The barcode technology was first patented in 1949, but engineers introduced the UPC code in the 1970s to meet the demand for better efficiency in grocery stores.

The story of barcodes did not begin in supermarkets but actually took shape in 1949. Two inventors, Norman Joseph Woodland and Bernard Silver, filed a patent for a product classification system based on concentric circles—an early version of a barcode that they called bull’s-eye code. The idea came to Woodland when he accidentally drew lines in the sand on a beach and realized that the lines could represent data like Morse code.

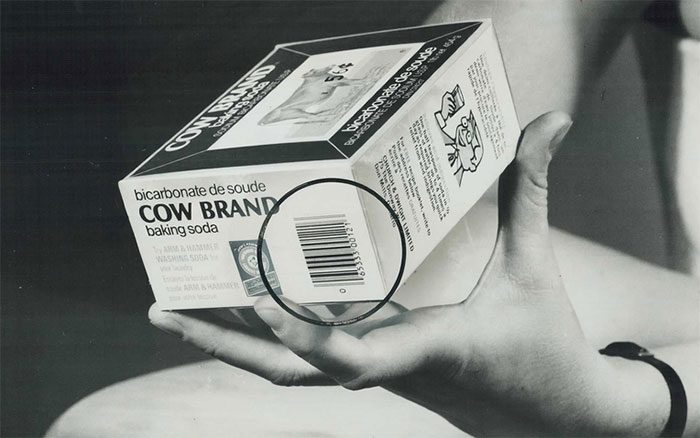

Barcodes commonly seen on products.

However, this invention faced technical hurdles. The system required a powerful 500-watt light source and a special converting tube, making it complex and difficult to use. Jordan Frith, a professor of Communication at Clemson University, argued that Woodland’s system was ahead of its time, requiring conditions that could not be met at that point.

In addition to the bull’s-eye code, there were other efforts to create product scanning systems. In 1967, the KarTrak system was introduced to identify and track goods on trains. Although KarTrak used color barcodes scanned by lasers, it failed due to incompatibility with computer systems and was affected by harsh weather, making code reading difficult.

In 1969, IBM started to focus on developing a more efficient product identification system. Paul V. McEnroe, the head of the barcode development team, was tasked with finding an innovative solution without the pressure of profitability in the early stages. Alongside marketing expert Sarkis Zartarian and engineer Mort Powell, McEnroe suggested that IBM should enter the sales industry.

Barcodes are used in many fields.

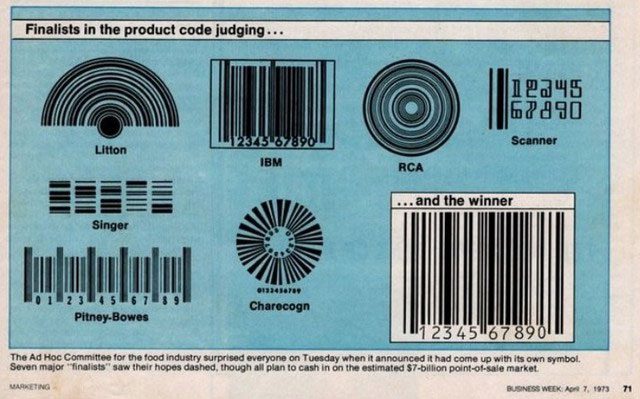

McEnroe’s team quickly delved into research and development, attracting talented engineers from various backgrounds. One of the most important members of the team was George Laurer, who demonstrated that Woodland’s bull’s-eye code would not meet long-term needs due to space limitations and printing accuracy. Instead, Laurer developed a simple linear barcode design with parallel bars that could be scanned from any direction.

While the IBM team was developing the UPC barcode, a competition was held by the National Association of Food Chains (NAFC) in 1972 to find the best product identification system. IBM submitted its UPC barcode design, competing against six other companies, including Woodland’s original bull’s-eye code. Ultimately, IBM’s design won for its feasibility and high efficiency, marking a significant turning point for the emergence of the UPC code.

During this process, Woodland also contributed significantly to IBM’s success. He, the inventor of the bull’s-eye code, joined IBM’s research team and supported improvements to the UPC code, giving IBM a major advantage in the competition. With tireless efforts, McEnroe’s team convinced the NAFC to adopt their barcode as the common standard.

Barcodes have changed the way we interact with the world.

After the UPC was approved, IBM developed the hardware and software to support barcode scanning. However, implementation was not easy. Some stores refused to adopt barcodes for fear of losing jobs for employees. Others expressed health safety concerns regarding the use of laser scanners, prompting IBM’s team to hire a testing company to ensure that the scanners posed no harm.

Carol Tucker-Foreman, director of the Consumer Federation of America, initiated a movement against barcodes, arguing that the UPC eroded price transparency. According to her, when individual price tags were eliminated, consumers lost the ability to compare prices. States like New York and California even enacted laws requiring price labels on every product.

Despite facing opposition, barcodes gradually gained recognition due to their significant cost advantages and accuracy in inventory management. By the early 1980s, the UPC began to be adopted by many major grocery stores, and by 1989, barcodes were widely used in over half of total sales in the U.S.

Barcodes are gradually recognized for their superior cost and accuracy benefits in inventory management.

Although the UPC barcode is the collective effort of a team, Paul McEnroe believes that George Laurer deserves the most credit. At the end of his life, Laurer was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his contributions. Interestingly, none of the IBM team members became wealthy from the barcode, as they all agreed to relinquish ownership rights to place the code in the public domain. This was a humanitarian decision that allowed barcodes to become a global tool for everyone.

Today, barcodes are not only used in retail but also in other industries such as healthcare, transportation, and even on self-driving vehicles on Mars. From an invention on a beach to a global management tool, barcodes have changed the way we interact with the world, optimizing efficiency and supporting businesses in their growth processes.

Barcodes are not just a technology; they are a testament to innovation and the power of science in turning ideas into reality. Their widespread adoption has become a symbol of a connected, transparent, and ever-advancing economy.