The Universe May Have “Cracks,” Resulting from the Big Bang.

In the fabric of spacetime, there might exist cracks that human telescopes cannot detect. These could be the remnants from the moment right after the Big Bang, when the temperature of the universe decreased rapidly.

This cooling process, referred to by scientists as the “transition phase,” can be visualized as low-temperature bubbles expanding everywhere, merging with other bubbles. Ultimately, the entire universe transitioned into a cooler state.

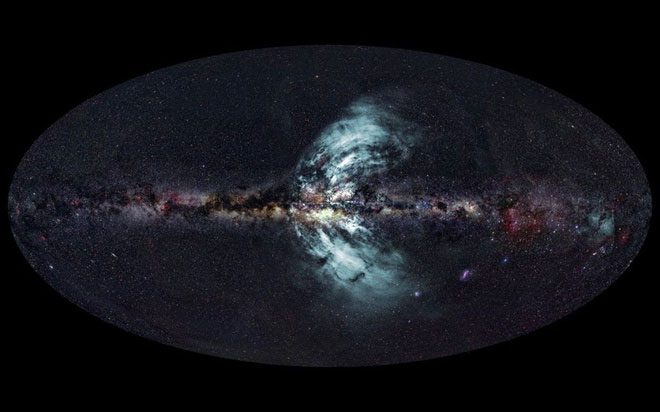

Do cosmic cracks exist, formed after the Big Bang? (Image: Optical Image).

This transition phase could leave cracks at the boundaries of cooled regions. Some physicists refer to these as “cosmic strings,” located in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), though current telescopes have not yet been able to observe them.

“Have you ever walked on a frozen lake? Can you see the cracks deep below the surface? The surface of the lake is very solid, yet there are cracks underneath,” explains physicist Oscar Hernandez from McGill University, Canada.

“Ice is just water that has undergone a transition. Water molecules move freely in liquid form, then suddenly form hexagonal crystals when frozen. Now imagine a series of hexagonal crystals snugly fitting together at one end, while at the other end, water crystals are just beginning to form. It is almost impossible for them to fit perfectly with the crystals at the lake’s edge,” Mr. Hernandez elaborates on his theory to explain cosmic cracks.

In a vast lake, the intersections between water crystals create cracks. In the universe, spacetime cracks give rise to cosmic strings. Searching for these cosmic strings could help affirm that current physical models need further refinement to adequately explain the laws of the universe.

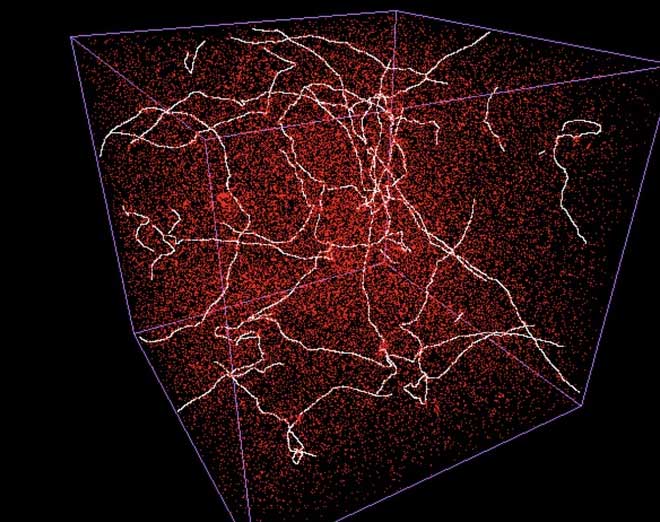

An illustration of cracks in the universe. (Image: C. Ringeval).

“Many models have been developed from the standard model, with theories such as superstrings, all leading to the existence of cosmic strings. It can be said that cosmic strings are an entity that many models predict to be real; thus, if they truly do not exist, all models would be incorrect,” Mr. Hernandez explains.

Previously, scientists primarily used methods of collecting data from the CMB and then simulated it through neural network models. However, in a newly published scientific paper, Mr. Hernandez and his colleagues suggest that observing the CMB will not provide enough clean data for neural networks to detect cosmic strings.

Another method being considered is to measure the universal expansion in all directions. Although these observatories are not yet completed, this could be the best method to confirm the existence of cosmic cracks.