Most urban residents are unaware of the hidden waterways beneath their feet, and many cities have forgotten rivers that have been buried for centuries.

River Bièvre once flowed through the Left Bank area of Paris, France, merging with the Seine River near the Austerlitz station. In the 1800s, writer Victor Hugo described this river as a quaint urban oasis, and its waters were rumored to possess magical properties.

Buried Waterways

However, over time, water mills, tanners, and shoemakers began to cluster around the Bièvre. By the mid-19th century, it had become a health hazard. The urban transformation led by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann gradually buried the Bièvre until it completely disappeared from the Paris map in 1912.

Burying rivers underground is not a solution, as they still exist; we must learn to coexist with these rivers.

Since then, several attempts to revive the Bièvre have failed. Until 2020, the Paris city council announced plans to restore the forgotten waterway as part of an ambition to bring nature back to the city. These water bodies could mitigate the urban heat island effect by absorbing heat and could also help prevent flooding by capturing excess rainfall that exceeds the resilience of the drainage system.

“The revival of the Bièvre River is no longer an unrealistic hypothesis,” said Dan Lert, the deputy mayor responsible for climate, water, and energy, after Mayor Anne Hidalgo was re-elected in 2020. “The demand for a cleaner and greener Paris is real.”

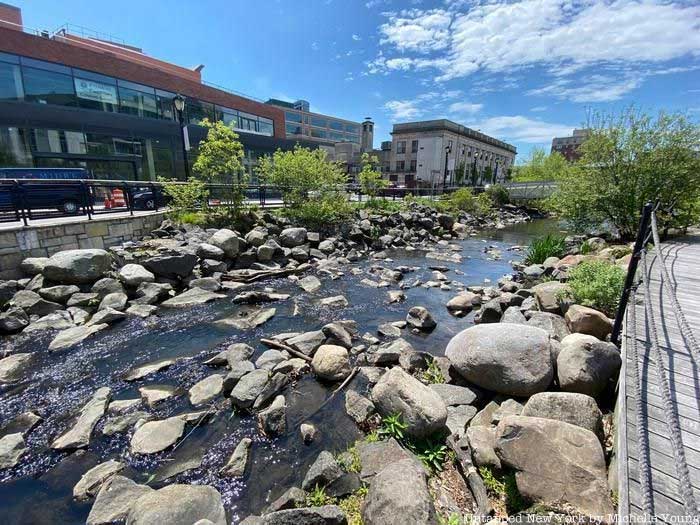

An urban stream in Yonkers, New York. (Photo: Untapped New York).

The Bièvre is not the only urban river undergoing a revival. Around the world, the process of revitalizing rivers is slowly but surely taking place. In 2014, Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city, revived streams named Fairburn and Parahiku.

The city of Sheffield, England, successfully revived the Porter Brook in 2016. Over the past decade, Yonkers in New York, USA, has brought the Saw Mill River back to light after being buried since the 1920s. Madrid (Spain), Manchester (England), and New York City (USA) are also considering similar restoration projects.

Most of these urban rivers were buried during the urbanization of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As water quality declined, they gradually transformed into underground sewers, sometimes becoming mere drainage ditches. This also contributed to flood prevention.

Bringing Waterways Back to Light

However, with today’s technology and techniques, keeping them underground often no longer makes sense. In fact, cities are realizing that bringing old rivers back to the surface can help adapt to climate change.

“Burying rivers underground is not a solution because they are still there; we must coexist with these rivers,” said Adam Broadhead, a scientist at the sustainable development firm Arup, which studies global river restoration projects.

The Ravensbourne River in London. (Photo: The Lost Byway).

“When discussing how to adapt to climate change in the future, the most sustainable approach is to consider whether we can coexist with rivers as open waterways again, and I believe that, upon thoughtful consideration, the answer is yes. You can see many examples of this,” Broadhead affirmed.

As heavy rainfall becomes more common, cities are increasingly vulnerable to flash floods. In Sheffield, where sewers have collapsed in recent years, bringing Porter Brook back to its former state has been seen as a flood prevention project. It has been so successful that other projects to clean and develop the Sheaf and Porter rivers are underway.

“Sewers across England are nearly 200 years old and are starting to deteriorate,” Broadhead said. “If they become blocked, which happens frequently, it creates a maintenance burden, so reopening them will improve flood risk management.”

What is Daylighting?

Although still a relatively unfamiliar topic for most people, daylighting is not a new concept. The city of Zurich, Switzerland, has been doing this since the late 1980s, and this practice (known in Swiss as Bachkonzept or “stream concept”) has even been incorporated into law to prevent clean water from mixing with polluted pipes.

Today, Zurich has brought back about 15 kilometers of streams flowing through the city, which feed into the famous lake of the same name or the Limmat and Glatt rivers.

We are at the source of several major rivers, such as the Rhine and Rhône. We have clean water from the source, so we strive to ensure that it remains clean as it flows through our country.

Having clean water flowing through rivers instead of sewers is seen as an opportunity to revitalize specific areas and improve quality of life. This also helps make wastewater treatment systems more efficient. The streams divert from 200 to 250 liters of clean water from the drainage system every second, significantly reducing wastewater treatment costs.

“You can save money because you don’t have to build such large wastewater treatment plants,” said Markus Antener, who has worked on the Bachkonzept at the Zurich city council since the project’s inception. However, he also pointed out that Switzerland has a unique approach to water quality.

“We are at the source of several major rivers, such as the Rhine and Rhône. We have clean water from the source, so we strive to ensure that it remains clean as it flows through our country,” Antener said.

One of the largest and most notable urban streams to be restored is Cheonggyecheon in the capital of South Korea, Seoul. It was revitalized in 2005 and is credited with helping to rejuvenate an entire neighborhood.

Once brought back to light where a highway once stood, Cheonggyecheon Stream (Cheonggye Stream) and its surrounding area have been transformed into a park where people gather to stroll, picnic, or socialize after work.

Arcadia Creek in Kalamazoo, Michigan, built from 1982 to 1995. (Photo: City-Data).

Broadhead believes that Cheonggyecheon is not a true daylighting project, as the stream still flows in underground sewers and water flows from fountains at the source. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that Cheonggyecheon has contributed to popularizing the daylighting concept and demonstrating its benefits.

“It is a really good example of the daylighting culture, as it is one of the most iconic cases and it helps raise awareness about daylighting,” Broadhead said.

In London, Broadhead is implementing a Branch Hill pond opening project at the edge of Hampstead Heath, a historic health facility. He hopes this project will spark greater interest among residents in the forgotten Westbourne River nearby.

“If it can help people realize that there is a stream flowing through their living area, that would mean something for the environment. But it will also serve as a small seed planted to encourage them and future generations to think about where they can revive even more rivers,” Broadhead said.