The mortality rate for smallpox was 30%, surpassing that of Covid-19 and is considered the deadliest epidemic in history; fortunately, smallpox has been eradicated thanks to vaccines.

According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), Covid-19 has killed around 15 million people to date (including unreported cases). The mortality rate of the disease is 0.7% of the total number of infected individuals.

However, the history of world medicine records an even more catastrophic epidemic with a mortality rate of up to 30%. This is smallpox, which primarily attacked infants. This disease was a nightmare in the previous century but was completely eradicated in 1980. Humanity spent centuries, rather than months, developing an effective vaccine to prevent this disease.

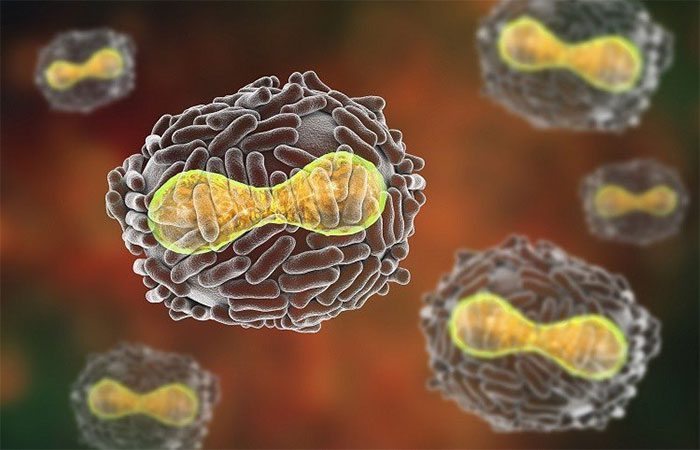

Smallpox is caused by two strains of the virus: Variola major and Variola minor.

Currently, in wealthy countries, the mortality rate from infectious diseases in infants is low. Most diseases have available vaccines and treatments. This is one of the greatest medical advancements of humanity. The complete eradication of smallpox is an important part of that progress.

Smallpox is caused by two strains of the virus: Variola major and Variola minor. The characteristic symptoms include fever, followed by a rash and red spots all over the skin. The more severe strain from the Variola major virus kills about 30% of those infected, with an even higher mortality rate among infants. Patients typically die within 8 to 16 days. Variola minor has similar symptoms but only causes death in about 1% of patients.

The basic reproduction number (R0) of smallpox is between 5 and 7, meaning that each infected person would infect approximately 5 to 7 others, nearly equivalent to the Delta or Omicron variants of Covid-19.

The world successfully pushed back against dangerous pathogens like smallpox primarily due to effective vaccination campaigns. Before modern vaccines were developed, people devised many ways to gain immunity to the virus.

In China, in the early 15th century, many healthy individuals intentionally inhaled smallpox scabs through their noses to contract a milder strain of the disease. About 0.5 to 2% of cases resulted in death from this “homemade vaccine,” but it also significantly improved the overall immune status of the community.

In England, in 1796, Dr. Edward Jenner demonstrated that contracting a mild strain of the smallpox virus would help produce antibodies. Since then, all of Europe began a serious race to develop vaccines. By 1813, the U.S. Congress passed a law ensuring the supply of smallpox vaccines, controlling the outbreak of the virus throughout the 1800s.

The rest of the world undertook similar efforts, with varying degrees of success. In 1807, Bavaria enacted mandatory smallpox vaccination regulations. In 1810, Denmark took similar action. Vaccination programs then continued across Europe.

By 1900, smallpox was no longer a threat in the wealthiest countries in the world. The mortality rate after contracting the disease had dropped to 1%. Nordic countries declared they had successfully eradicated the virus. In the following decades, the U.S. and Canada also reported having pushed back the pathogen.

Nearly 900,000 students were vaccinated against smallpox at a school in New York State, USA. (Photo: NY Daily News)

However, while smallpox was still devastating in other parts of the world, vaccination programs remained necessary to ensure the virus did not resurface. In the first half of the 20th century, the world still recorded between 10 to 15 million cases and about 5 million deaths annually due to smallpox.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a global effort to eradicate the virus. WHO provided a common framework for countries to coordinate this mission.

The initial obstacle was skepticism within the scientific community regarding the feasibility and practicality of the idea of eradicating an infectious pathogen, according to Donald Ainslee Henderson, former director of the disease surveillance department at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Previously, humanity had never completely defeated any epidemic. The world had billions of people under numerous governments, many living in war zones.

However, medical advancements realized the hopes of the medical community. During this period, syringe technology improved. A dual-branch syringe helped save vaccines. International travel became easier, facilitating the transport of vaccines and the deployment of public health personnel to various countries.

The outbreak in 1947 in New York City, USA, which originated from a traveler from Mexico, spurred a rapid response. Authorities vaccinated 6 million people within 4 weeks.

Smallpox also possesses characteristics that make the pathogen easier to eradicate. The virus cannot reside in animals. This means it does not have the ability to linger in wild populations, waiting for an opportunity to resurface in humans like Ebola and various strains of coronavirus. Once it is no longer infectious in humans, smallpox will disappear permanently. Those who have naturally recovered from the disease or have been vaccinated will have lifelong immunity.

Additionally, the virus primarily causes clear symptoms, with an incubation period of about one week. This characteristic allows public health officials to detect the disease and implement a “ring vaccination” strategy. Whenever an infection is reported, they immediately vaccinate those who have come into contact with the infected individual to prevent further spread.

Mr. Henderson referred to the ring vaccination campaign as a turning point in the fight against smallpox. Instead of attempting to vaccinate 100% of the world’s population (which was impossible in low-income countries), this strategy allowed health teams to focus on the most critical areas.

As many countries declared themselves free of smallpox, resources shifted to areas experiencing outbreaks.

In 1977, the world marked the last smallpox outbreak in Somalia. Doctors monitored and vaccinated all close contacts, and none of them contracted the disease.

Two years later, on May 8, 1980, the World Health Assembly declared that smallpox had been completely eradicated globally.

For more than four decades, the world has not been able to replicate this success. The ring vaccination strategy has been applied in efforts to combat other diseases, most recently Ebola.

However, viruses of the century, such as HIV, or long-standing pathogens like coronaviruses, have generally not been eradicated. Part of the reason is that these viruses can reside in animals. Others, like HIV, often transmit silently without symptoms, making detection difficult.

Nevertheless, the victory over one of the most dangerous pathogens in history still leaves many lessons in the field of health.

First, smallpox eradication programs and other infectious diseases require the efforts of a well-supported public health system. The efforts of frontline health workers only make sense when governments coordinate actions, ensuring that poorer countries are not left behind.

The efforts to push back smallpox also demonstrate the importance of vaccine distribution, infrastructure, and the essential role of international coordination. WHO and the disease control centers of various countries need effective funding, attracting top scientific talent and remaining unaffected by political goals.