Without the support of modern technology, ancient cartographers needed a significant amount of time and had to gather information from various sources.

Ancient mapmakers relied on a combination of art, exploration, mathematics, and even imagination to capture the vastness of the lands they knew and many lands they believed existed. In many cases, these early maps served both as navigational aids and as representations of mysterious wonders.

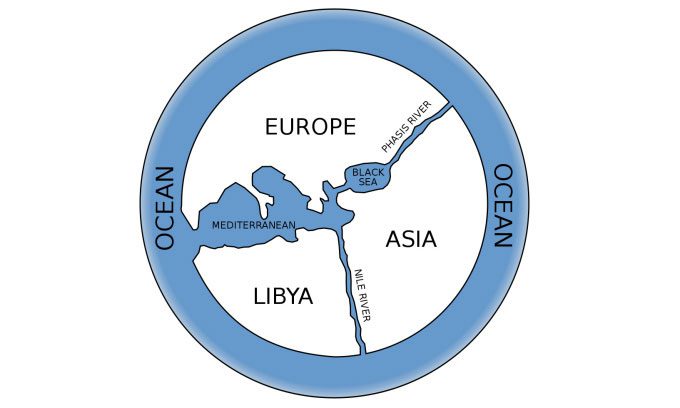

The “known world” map by Anaximander. (Image: Wikimedia).

To create maps, ancient peoples required an extensive amount of time. Maps were the result of many generations of travelers, explorers, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, historians, and other scholars coming together to compile discrete pieces of information. Thus, these early works were based on some real measurements but also relied heavily on speculation.

One of the first detailed descriptions of the “known world” was created by Anaximander, a philosopher who lived around 610 – 546 BC, and is considered one of the seven sages of Greece. The phrase “known world” is emphasized because Anaximander’s circular map displayed the land of Greece (at the center of the world) along with parts of Europe, South Asia, and North Africa. To the philosopher, these continents fit together in a circular shape surrounded by water. At that time, the earth was believed to be flat.

In the 1st century BC, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, a Greek scholar, calculated the circumference of the blue planet by comparing survey results collected at the Library of Alexandria. While many believed earlier that the earth was round, modern scientists have no recorded evidence detailing how they measured the earth’s circumference. However, Eratosthenes’ case is an exception.

Eratosthenes’ method was quite simple and can easily be performed by anyone today. He measured the length of the shadow cast by a vertical stick in two cities on the same day. The north-south distance between the two cities and the angles measured provided a ratio that allowed him to calculate the earth’s circumference fairly accurately (about 40,000 km). After Eratosthenes published his results, maps depicting a flat earth continued to circulate for a while but eventually faded.

Eratosthenes also developed a method for more accurately locating places. He used a grid system—similar to the systems on modern maps—that divided the world into many parts. This grid system allowed individuals to estimate their distance from any recorded location. He also divided the known world into five climatic zones—two temperate zones, two polar zones in the north and south, and one tropical zone around the equator. This resulted in a much more complex map that represented the world in greater detail.

In the following centuries, maps became more complex as Roman and Greek cartographers continued to gather information from travelers and military expeditions. Compiling documents, the scholar Claudius Ptolemy wrote the famous book Geographia and the maps based on it.

Ptolemy’s work, compiled around the year 150, relied heavily on older sources. However, what made Ptolemy influential was his clear explanation of how he created his work, allowing others to replicate his techniques. Geographia contained detailed coordinates for every place he knew (over 8,000 locations). Ptolemy also introduced the concepts of latitude and longitude that people still use today.

Geographia was introduced to Europe in the 15th century. For many years, Islamic scholars reviewed, examined, and even modified Ptolemy’s work. His work, along with new maps from influential geographers like Muhammad al-Idrisi, became extremely popular among explorers and mapmakers in the Netherlands, Italy, and France by the mid-18th century.

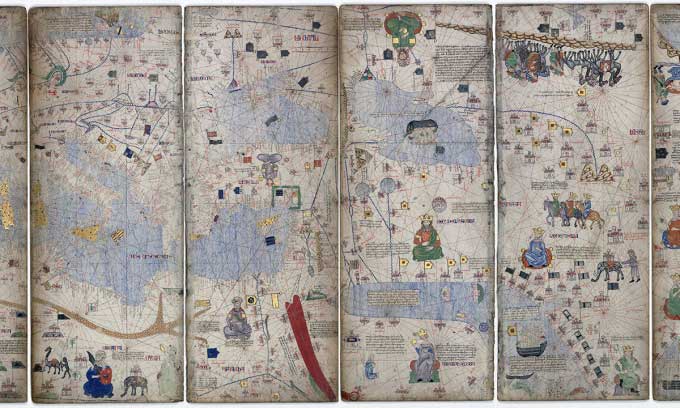

A portion of the Catalan Atlas. (Image: Wikimedia).

A significant development in cartography was the introduction of the magnetic compass. Although knowledge of magnetism had existed for a long time, its application in reliable navigation devices only began around the 13th century. The compass rendered many old maps obsolete for navigation. This was followed by the emergence of portolan charts, a type of maritime guide used for navigation between ports.

A notable example of a portolan chart is the Catalan Atlas, created by cartographers for King Charles V of France. They produced the map by synthesizing information from various sources. It remains unclear who the exact authors were, but many experts believe the map was created by Abraham Cresques and his son, Jahuda.

The Catalan Atlas is filled with information about real locations but also includes many fantastical details. This discrepancy arose from compiling the map from many different sources, including travelers’ tales and mythology. As a result, monsters, dragons, sea creatures, and imaginary lands continued to appear on many maps for a long time thereafter.