Whether intentional or not, the way large settlements were constructed in Southeastern Europe 6,000 years ago may have limited the spread of disease.

A new study focusing on the first farmers in Europe raises a curious pattern over time: These farmers lived in large, densely populated villages, then dispersed over centuries, only to form cities again, which they subsequently abandoned. Why is this the case?

Archaeologists often explain what we call the urban collapse in terms of climate change, overpopulation, social pressures, or a combination of these factors. However, scientists have added a new hypothesis to the mix: disease. Living in close quarters with animals led to the transmission of infectious diseases from animals to humans. Outbreaks could cause densely populated settlements to be abandoned, at least until later generations figured out how to arrange their settlements to be more resilient to disease.

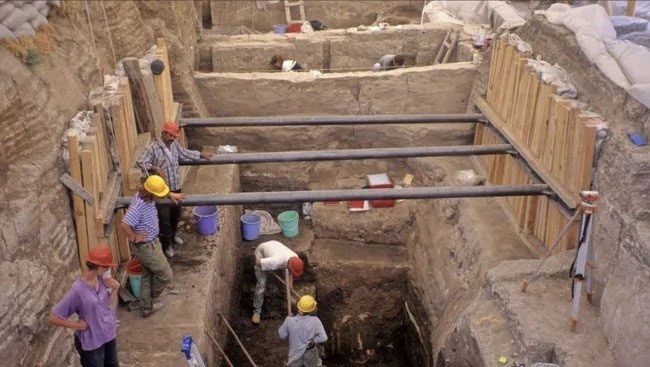

Excavations at Çatalhöyük reveal how people lived closely together before the settlement’s collapse. (Photo: Mark Nesbitt/Wikimedia Commons).

The First Cities: Many People and Animals

Çatalhöyük, located in present-day Turkey, is the oldest agricultural village in the world, dating back over 9,000 years. Thousands of people lived in mud-brick homes so tightly packed that residents had to enter through a ladder via a hatch on the roof. They even buried chosen ancestors beneath the floors of their homes. Despite the ample space available in the Anatolian Plateau, people continued to crowd together.

For centuries, the residents of Çatalhöyük herded sheep and cattle, cultivated barley, and made cheese. Sensual paintings of bulls, dancing figures, and a volcanic eruption evoke their folklore. They kept their homes tidy and clean, sweeping the floors and maintaining storage containers near the kitchen, located beneath the hatch to allow smoke from the stove to escape. Maintaining hygiene meant they even replastered the interior walls of their houses multiple times a year.

These traditions came to an end around 6000 BCE when Çatalhöyük was mysteriously abandoned. The population dispersed into smaller settlements across the surrounding floodplains and beyond. Other large agricultural populations in the region also scattered, and nomadic animal husbandry became more common. For those populations that persisted, the mud-brick houses were now separated, in contrast to the clustered homes of Çatalhöyük.

Was Disease a Factor in the Abandonment of Densely Populated Settlements in 6000 BCE?

At Çatalhöyük, archaeologists found human bones mixed with animal bones in burial mounds and refuse. The close quarters of humans and animals may have caused zoonotic diseases at Çatalhöyük. Ancient DNA identified tuberculosis (TB) from local cattle dating back to 8500 BCE and traces of TB in the bones of infants shortly thereafter.

DNA from ancient human remains identified salmonella dating back to 4500 BCE. Assuming that the transmissibility and virulence of Neolithic diseases increased over time, densely populated settlements like Çatalhöyük may have reached a threshold where the impact of disease outweighed the benefits of living in close quarters.

Around 4000 BCE, large urban populations re-emerged in the major settlements of the ancient Trypillia culture west of the Black Sea. Thousands lived in large Trypillia settlements like Nebelivka and Maidanetske, located in present-day Ukraine.

If disease was a factor leading to dispersion millennia ago, how could these large settlements survive?

Simulating Neighborhoods with Social Distancing

To simulate disease spread at Nebelivka, researchers had to make a few assumptions.

- First, they assumed that diseases initially spread through food, such as milk or meat.

- Second, they assumed that people visited other homes in their neighborhood more frequently than those outside their neighborhood.

Would this clustering of residences be enough to prevent a disease outbreak? To test the impact of different interaction rates, researchers ran millions of simulations, first on a network representing clusters of residences. They then reran the simulations, this time on a virtual layout modeled after actual floor plans, where houses in each neighborhood had a higher chance of interacting with one another.

Based on these simulations, researchers found that if people visited other neighborhoods less frequently than they visited other homes in their own neighborhood, the arrangement of housing clusters in Nebelivka would significantly reduce the initial outbreaks of foodborne illnesses. This is logical, as each neighborhood had its own cluster of homes. Overall, the results suggest that the Trypillia layout may have helped early farmers live together in low-density urban populations at a time when zoonotic diseases were on the rise.

Residents of Nebelivka did not need to consciously plan their neighborhood layouts to help their population survive. However, they may have done so, as it is human instinct to avoid signs of infectious disease. Like those in Çatalhöyük, residents kept their homes clean. About two-thirds of the houses in Nebelivka were intentionally burned at different times. These periodic, intentional burnings may have been a pest eradication strategy.

Some early diseases eventually evolved to spread through means other than bad food. For example, tuberculosis became airborne at some point. When the bacteria causing the plague adapted to fleas, it could spread through rats, a species unconcerned with neighborhood boundaries.

The world’s first cities, along with cities in China, Africa, and the Americas, form the foundation of civilization. It can be said that their shape and function were shaped by millennia of disease and human responses to them, stemming from the world’s first agricultural villages.