The 24-hour system we use today likely originated from the astronomical observations of the Egyptians over 4,000 years ago.

The relationship between humans and time has formed long ago, and understanding the origins of many time measurement units poses a significant challenge for experts. Some units stem from fairly straightforward astronomical phenomena that can be independently observed across various cultures worldwide. For example, measuring the length of a day or a year can be based on the relative movement of the Sun concerning the Earth, while measuring months relies on the phases of the Moon.

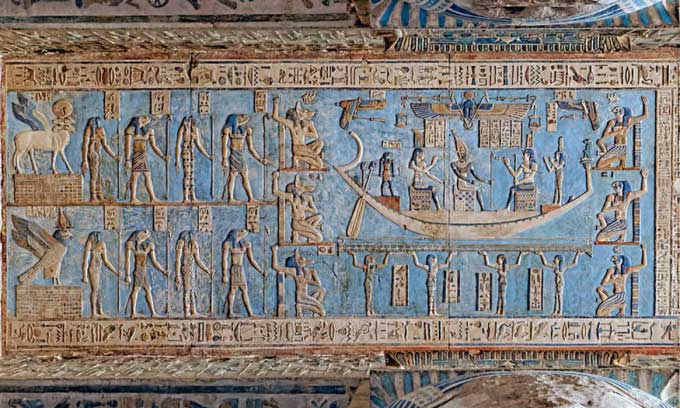

A part of the astronomical ceiling at the Dendera Temple, Egypt. (Photo: Kairoinfo4u).

However, some time units have no clear connection to any astronomical phenomena, such as weeks and hours, according to Associate Professor of Astronomy Robert Cockcroft and Interdisciplinary Science Professor Sarah Symons at McMaster University. One of the oldest types of writing, Egyptian hieroglyphics, provides information about the origins of the hour. It originated in North Africa and the Middle East, was adopted in Europe, and then spread across the globe, IFL Science reported on July 8.

Time in Ancient Egypt

The Pyramid Texts, written before 2400 BCE, are the earliest records of ancient Egypt. Within the texts, there is the term wnwt (pronounced roughly as “wenut”), and the hieroglyph associated with this word is a star. Based on this, experts deduce that wnwt relates to nighttime.

Wnwt is now translated as “hour,” and to explore this term, we first need to look at the city of Asyut around 2000 BCE. There, the interior of rectangular wooden coffin lids was sometimes decorated with astronomical tables.

The table contains columns representing 10-day intervals within a year. The ancient Egyptian calendar had 12 months, each with 3 weeks, and each week consisting of 10 days, followed by a series of 5 festival days at the end of each year. In each column, the names of 12 stars are listed, forming 12 rows. The entire table illustrates the changes in the sky over a year, similar to a modern star map.

These 12 stars represent the earliest systematic division to split a night into 12 time periods, each corresponding to one star. However, during this period, the term wnwt did not appear alongside the star tables in the coffins. It wasn’t until around 1210 BCE, during the New Kingdom period of Egypt (16th – 11th century BCE), that the connection between the number of rows and the term wnwt was clarified. For instance, in the Osireion temple at Abydos, there is an astronomical table on a coffin where the 12 rows are labeled with the term wnwt.

During the New Kingdom of Egypt, there were 12 wnwt for the night and 12 wnwt for the day, both aimed at measuring time. Thus, “wnwt” almost carries a meaning similar to the modern “hour,” except for two points.

First, although there are 12 hours of day and 12 hours of night, they were represented separately rather than combined into a 24-hour day. Daytime was measured based on the shadow cast by the Sun, while nighttime was primarily based on the stars. This could only be performed when both the Sun and stars were in sight, meaning there were two times close to dawn and dusk that contained no hours.

Second, wnwt differs from the current hour in length. The length of wnwt varies throughout the year, with nighttime hours near the summer solstice being longer and daytime hours near the winter solstice also being longer.

The Osireion temple at Abydos provides much astronomical information. (Photo: Hannibal Joost).

The Stars that Measure Time

To answer where the numbers 12 or 24 come from, we must investigate why the Egyptians chose 12 stars for each 10-day period. This choice also marks the true origin of the hour.

The ancient Egyptians used Sirius (or the Dog Star, the brightest star in the night sky) as a model and selected other stars based on their activity similarities with Sirius. The key factor for selection seems to be their disappearance for 70 days each year, similar to Sirius, even though they were not as bright. Every 10 days, a star similar to Sirius would disappear and another star would reappear.

Depending on the time of year, each night, 10 to 14 such stars would become visible. By recording the 10-day intervals throughout the year, experts obtained a chart resembling the astronomical table in the coffins.

Therefore, it is highly likely that the choice of 12 as the number of nighttime hours (which ultimately led to a total of 24 hours in a day) was related to the selection of a 10-day week. Thus, the hours of modern humanity trace their roots back to decisions made over 4,000 years ago.