Countries are striving to save rivers and oceans that have ‘died,’ reviving them from ecological disasters.

According to the organization The Ocean Cleanup, rivers are a major source of plastic waste entering the oceans. They estimate that 1,000 rivers across the continents are responsible for 80% of the annual riverine plastic waste globally, which ranges from 0.8 to 2.7 million tons each year. Among these, small urban rivers are among the most polluting. The remaining 20% of plastic waste is distributed across 30,000 other rivers.

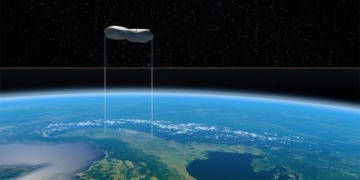

A river waste filtering system in operation. (Photo: Green Matters).

So, what are governments, NGOs, and businesses doing to save water sources—the lifeblood of all living beings on the planet? Below are a few examples that are operating effectively.

Indonesia Saves the “Dirtiest River in the World”

Cleaning the Citarum River is one of the long-term efforts in Indonesia addressing the water crisis. The Citarum is the longest and largest river in West Java, approximately 297 km long. It flows through thousands of settlements on the island, connecting villages and residents of Indonesia’s most populous province, with 25 million people.

Green Cross Switzerland and Pure Earth have listed the Citarum among the top 10 most polluted places in the world. This is truly an ecological disaster, as the water in the Citarum is clogged with household waste and chemicals from thousands of factories, primarily from the textile industry.

Mountains of waste pile up along the riverbanks, and residents are forced to live with the “flood of trash.” According to the Asian Development Bank in 2013, about 9 million people live near the river, where coliform bacteria levels exceed mandatory limits by more than 5,000 times.

A section of the Citarum River, where people often dump trash directly into the river instead of burning it. (Photo: Guardian)

Severe pollution causes a range of health issues such as dermatitis, rashes, gastrointestinal problems, kidney failure, chronic bronchitis, and tumors. The reason is that most local residents have to use contaminated water directly from the river for bathing, washing clothes, as well as for drinking and cooking. Environmentalists estimate that at peak times, 20,000 tons of waste and 340,000 tons of wastewater flow into this river each day.

A girl bathing her sibling with water from the polluted river in the Citarum basin. (Photo: Mongabay)

Finally, in 2018, the severe pollution issue forced Indonesian President Joko Widodo to announce a 7-year program to restore the Citarum River to its natural and clean state. This ambitious program aims to make Citarum’s water drinkable by 2025, with an estimated cost of $4 billion. Since then, 7,000 soldiers, police, and volunteers have been deployed to clean the river.

The goal may be ambitious, but according to village chief Bapak Cece in a riverside village, things have improved somewhat. Cece stated in 2023: “Now people can fish in the river, and children can swim, especially when it rains.”

In February 2023, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), with support from the European Union (EU), coordinated with the Indonesian Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Investment to train 40 companies operating along the Citarum River, including both private and state-owned enterprises, on responsible business practices by applying the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP).

The Citarum River flowing through Bojongsoang Subdistrict in southern Bandung. (Photo: Mongabay)

Generation Foundation, an Indonesian NGO, along with Waste4Change and RiverRecycle, has set up a plastic collection system to remove between 20 to 100 tons of waste each day. They place concentrated modules along the Citarum River to channel debris to collection points and scoop them up using collection wheels.

Waste removed from the river is used as biomass fuel. Meanwhile, non-recyclable plastics are converted into low-sulfur fuel to financially support this project.

An excavator cleaning waste on the Cikapundung River, a tributary of the Citarum. (Photo: Mongabay)

The efforts have begun to yield initial results. At the UNFCCC COP 26 summit in Glasgow, UK, West Java Governor Ridwan Kamil presented progress in restoring the Citarum, stating that the river has shifted from a state of “heavy pollution” to “light pollution.”

Cleaning the Oceans

The Ocean Cleanup is perhaps best known for its efforts to clean the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an initiative started by the young founder Boyan Slat in 2013 after a TED talk he gave on the subject went viral. According to CNBC, the company is now pursuing a dual goal rather than just focusing on the ocean (as indicated in its name); they are also developing a range of river cleaning technologies.

Slat stated: “Our goal is to remove plastic from the ocean. We are interested in rivers because we believe it is the fastest and most cost-effective way to prevent plastic from continuing to enter the ocean.”

The company’s first river cleaning device, known as the Interceptor Original, was launched in 2019. It is a barge powered entirely by solar energy. It includes a barrier and conveyor system specifically designed to isolate and filter plastic waste from the river. The uninterrupted flow design allows plastic to flow freely into the device while water continues downstream.

The Interceptor system in operation at Ballona Creek, California, USA. (Photo: The Ocean Cleanup)

The barrier collects debris as it flows with the current and directs it to a conveyor capable of absorbing water. At this point, the waste is transferred onto a conveyor to an automated shuttle to distribute it among one of six containers placed on a separate barge. Once full, the barge is swapped out, and the waste is transported to a local waste management facility.

In addition to the unloading, dumping, and reinstalling of waste collection barges, Interceptor uses solar energy, eliminating the need for expensive fuel or pollution, resulting in efficient operating costs and requiring minimal labor.

However, since this massive barrier device is not suitable for smaller rivers, the research team has developed another solution: an independent floating barrier to collect waste and a small mobile conveyor to scoop up trash and transport it to onshore waste containers. This system is currently being deployed at Kingston Harbor, Jamaica, where Slat noted that the rivers are too narrow for the Interceptor Original system.

The “Trashfence” solution – a trash barrier. (Photo: The Ocean Cleanup)

For rivers suffering from severe waste issues, they use the Trashfence solution. The operation is very simple: an 8-meter high steel barrier is anchored in the riverbed to trap waste during heavy storms. When the water recedes, excavators remove the accumulated waste.

However, their first version encountered issues as the volume of waste became too large, causing the system to overload, as seen in some of the most polluted rivers in Guatemala.

“The force of the flowing trash is too great, causing the Trashfence to collapse, unfortunately. Therefore, we are currently researching a second version and hope to be ready for the next rainy season,” Slat said.

As of the latest update, The Ocean Cleanup currently has 15 Interceptor systems being installed in 8 countries, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

“Trash Wheels” in the USA

Founder John Kellett proudly stands beside one of the company’s trash filtering devices. (Photo: Here & Now).

In the USA, Clearwater Mills is one of the pioneering organizations cleaning rivers. The “Trash Wheel” debuted in Baltimore, first launched in 2014, is one of the pioneering efforts to address the issue of river waste. Clearwater Mills founder John Kellett was inspired to design this trash filtering device after witnessing trash flooding into Baltimore Harbor during heavy storms for many years.

Kellett stated that the company has four trash filtering machines, each given a unique and interesting name such as Mr. Trash, Captain, and Professor, and they have become the “stars” of the city.

The operation of this type of machine is quite similar to the Interceptor. A V-shaped barrier is set up across the river, with rubber edges extending about 6 meters below the water’s surface. This device catches floating debris downstream and directs it towards the “mouth” of a water wheel that spins, powered by the river’s current and attached solar panels. The rotation of the wheel powers a conveyor belt that lifts the trash and debris out of the river and into a trash bin. Attached cameras allow the team to monitor the fullness of the bin.

“And when that bin is full, we have another barge that carries an empty bin. We take the full one out, insert the empty one, and continue collecting trash,” Kellett said.

By 2022, the four machines had collected a total of about 2,000 tons of trash and debris. Sticks and leaves made up most of this mass due to the lightweight nature of plastics, but it included around 1.5 million plastic bottles, 1.4 million polystyrene containers, and 12.6 million cigarette butts. Everything is then incinerated at a facility that converts waste into energy.

The entire system has filtered about 2,000 tons of trash in 8 years. (Photo: Business Wire)

Additional trash filtering machines are planned for Texas, California, and even Panama, where the local nonprofit Marea Verde has partnered with Clearwater Mills to manufacture a fifth machine named Wanda Díaz. The project is funded by the Benioff Ocean Initiative and the Coca-Cola Foundation, two organizations that jointly support a portfolio of river cleanup projects worldwide.

AlphaMERS in India

AlphaMERS, based in India, also employs the principle of setting up trash filtering systems, with 34 installations in 8 different cities across the country. It is much smaller than Ocean Cleanup’s Trashfence and is not designed for the same large volume of waste, but it can still handle quite a heavy workload. Made of stainless steel, the AlphaMERS barrier floats a few dozen centimeters above the water surface and extends about 5 meters down below the water.

The founder of AlphaMERS, D.C. Sekhar, stated: “The hydrodynamics and hydropneumatics of this system are very simple but very suitable for this work. And it is built very robustly, with heavy-duty steel chains holding it on both sides. Thus, it can withstand the monsoon flows right after the rain.”

The AlphaMERS floating barrier system. In 2018, these 8 barriers collected 22,000 tons of trash, 10% of which was plastic. (Photo: AlphaMERS)

Sekhar noted that his floating barrier system is very effective at preventing trash in fast-flowing rivers, whereas designs that rely on barriers and screens can fail when water levels rise, as water will flow over the barrier, carrying trash with it.

Eight floating barriers were deployed at various points along the Cooum River in Chennai in 2017. Sekhar mentioned that they collected about 2,400 tons of plastic in the first year of operation. To collect the filled trash, AlphaMERS also uses conveyor belts, similar to Clearwater Mills and The Ocean Cleanup.

While still making a difference, John Kellett does not want projects like his river cleanup to be seen as long-term solutions. (Photo: Baltimore Magazine)

However, when looking at the broader issue of global water pollution, despite their certain impact in the short and medium term, the aforementioned technologies cannot be considered sustainable or long-term solutions. Organizations such as The Ocean Cleanup and Clearwater Mills share the goal of removing as much waste as possible, but they also understand that river cleaning systems are not the optimal solution.

Kellett said: “One of the things we hope for is that the trash filters will no longer be needed, and that will only happen when we address the upstream issues to the extent that no trash can enter the water sources.”

Achieving this will be challenging and will depend on a combination of better waste management infrastructure, more sustainable packaging, reduced consumption, and greater public and corporate awareness about proper waste disposal.

Middle-income countries like the Philippines, India, and Malaysia produce the most ocean waste. People have enough money to buy many packaged goods, but waste collection infrastructure is still lagging behind. Not to mention the issues related to sustainable business or production, which is the responsibility of every enterprise and organization.

Sandy Watemberg, executive director of the nonprofit organization Marea Verde, is thrilled that her organization has brought the Wanda Díaz trash filter to Panama and is optimistic about its future operational effectiveness.

Watemberg said: “We are very hopeful that this will be a great success for our country.” However, she knows that real change will take longer.

“These types of technologies and projects are not the solution. We need to change our habits. We need to seek long-term solutions that allow us to have a cleaner and healthier environment because these types of projects help us raise awareness and minimize harm in the short and medium term. But ultimately, this is not something sustainable. We cannot let thousands of these projects run indefinitely.”

According to UN Water, currently 44% of the total wastewater on Earth returns to the environment untreated. Among this, human waste, household sewage, sometimes toxic waste, and even medical waste are directly discharged into the planet’s ecosystems. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that about 2 billion people worldwide are consuming contaminated water.

Additionally, the organization reports that 368 million people are using unsafe water sources. Furthermore, the majority of domestic waste originates from land; for this reason, many organizations with water cleaning initiatives are directing their focus and investment towards addressing the source—rivers that are home and production areas for billions of people.