Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering worked tirelessly overnight in a dilapidated facility with scant funding, all in the effort to develop a vaccine for whooping cough to protect children.

The two women were bacteriology experts based in Michigan. In late November 1932, they ventured out while most people were finishing their daily work. Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering visited infants suffering from whooping cough living in impoverished neighborhoods.

Whooping cough is no longer a significant threat to the public today, thanks to widespread vaccination. However, in 1932, the disease was a terrifying menace that haunted many families. Patients were described as “very pale, slowly dying in violent coughing fits or choking.”

Diagnosing whooping cough was challenging due to the disease’s easily mistaken symptoms. Initially, it appeared mild, causing only a runny nose and slight cough. Sometimes, children exhibited signs of apnea, only for their chests to quickly heave back to normal. Doctors could also mistake it for a common cold, deeming it not serious.

However, after one to two weeks, children could experience severe spasms, leading to breathing difficulties. Their bodies emitted sharp, wheezing sounds, choking as they struggled to get air down their throats. By this time, the illness had progressed to a severe stage. Life gradually dwindled over the course of three months, and very few doctors could intervene when whooping cough worsened.

“It was terrible; I wondered how patients managed to survive,” said Camille Locht, a researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Lille, France.

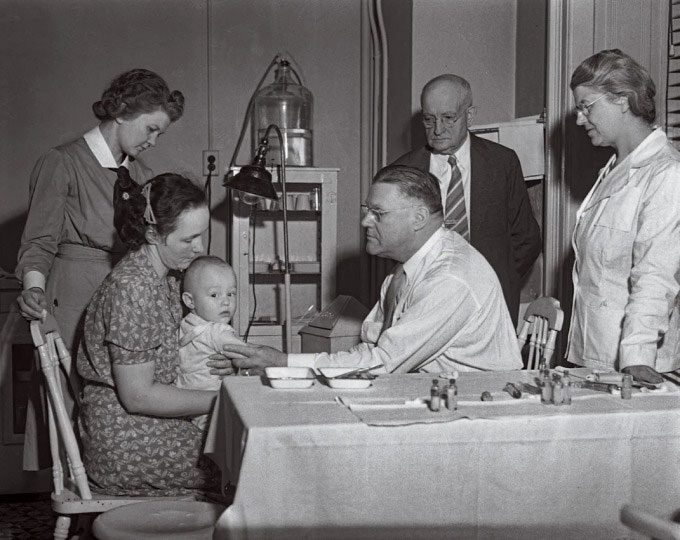

Kendrick, far right, observes a colleague administering whooping cough vaccine to children in 1942. (Photo: Grand Rapids History Center, Grand Rapids Public Library).

Back in the 20th century, whooping cough was highly contagious. An infected child could spread it to half of their classmates and all family members. Whooping cough caused up to 7,500 deaths in the United States during the 1930s, primarily among infants and young children. Survivors sometimes suffered permanent physical and cognitive damage.

The epidemic’s outlook began to change thanks to Kendrick and Eldering. Initially, the two scientists were tasked with routinely testing medical, environmental, and patient samples. However, whooping cough gradually consumed their thoughts. They worked late into the night, initially without funding, in a crumbling building.

They aimed for quicker, more accurate diagnoses, limiting infections and isolating patients as soon as possible. Armed with a Petri dish (a dish used to hold samples for microscopic examination), the two women rapidly cultured samples for analysis.

On November 28, 1932, the laboratory confirmed the first Bordetella whooping cough virus sample. From that point, Kendrick and Eldering aimed to track and control the whooping cough outbreak across the city. Due to a lack of funding, the scientists had to use sheep’s blood, which was cheaper, to culture the disease. This method allowed them to expand their experimental program for the whooping cough virus. By January 1933, just seven weeks after cultivating the pathogen, Kendrick and Eldering produced the first trial vaccine.

The vaccine formulation technique at that time was still rudimentary, akin to cooking without a recipe. To find an effective vaccine, scientists had to experiment with various methods. For whooping cough, prior to the work of these two experts, no entity had successfully formulated a vaccine. Repeated failures led the American Medical Association to reject the whooping cough vaccine in 1921, concluding that the injections “were completely ineffective for prevention” and “useless” for treatment.

The vaccine developed by Kendrick and Eldering was also formulated in the traditional way, involving killing bacteria with conventional disinfectants and then further purifying the product. However, the two women improved the formulation process to ensure the quality of vaccine batches was more consistent and effective for young children.

The first field study took place soon after, involving 1,592 children, with 712 receiving the vaccine and 880 in the control group.

However, Kendrick and Eldering had no prior experience with clinical trials, leading to extreme anxiety during the field research. After each vaccination session, the two women felt as though they were sitting on pins and needles, waiting for emergency calls regarding severe reactions.

Kendrick remarked: “I was terrified throughout the process; I hardly slept each night.”

However, no emergency calls about incidents came in. Instead, the research data showed promising results: the unvaccinated group had 63 cases, 53 of which were severe; while the vaccinated group had only 4 cases, all mild.

A kit from the late 1940s containing the first version of the whooping cough vaccine along with documentation outlining the benefits of vaccination. (Photo: Rachel Anderson).

Yet, due to the failures of many previous whooping cough vaccines, the trial results were not deemed reliable. Health officials requested Wade Hampton Frost, a prominent epidemiologist at the time working at Johns Hopkins, to comment.

He expressed skepticism: “There is a very high likelihood that Kendrick’s experiment has errors,” and subsequently visited the women’s laboratory to advise on improving the clinical trial.

The new study attracted over 4,000 participants, and the vaccine continued to prove its effectiveness. In 1944, the American Medical Association added Kendrick and Eldering’s vaccine to its recommended vaccination list.

As a result, the incidence of whooping cough in the country dropped by more than half within just ten years. The number of deaths decreased from over 7,500 in 1934 (the peak) to just 10 per year by the early 1970s. Kendrick also traveled to many other countries to administer vaccinations, saving countless young lives.

Michael Decker, a whooping cough expert at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, praised the two scientists for their persistence and belief that they could successfully create a vaccine, paving the way for future whooping cough vaccine research.